|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

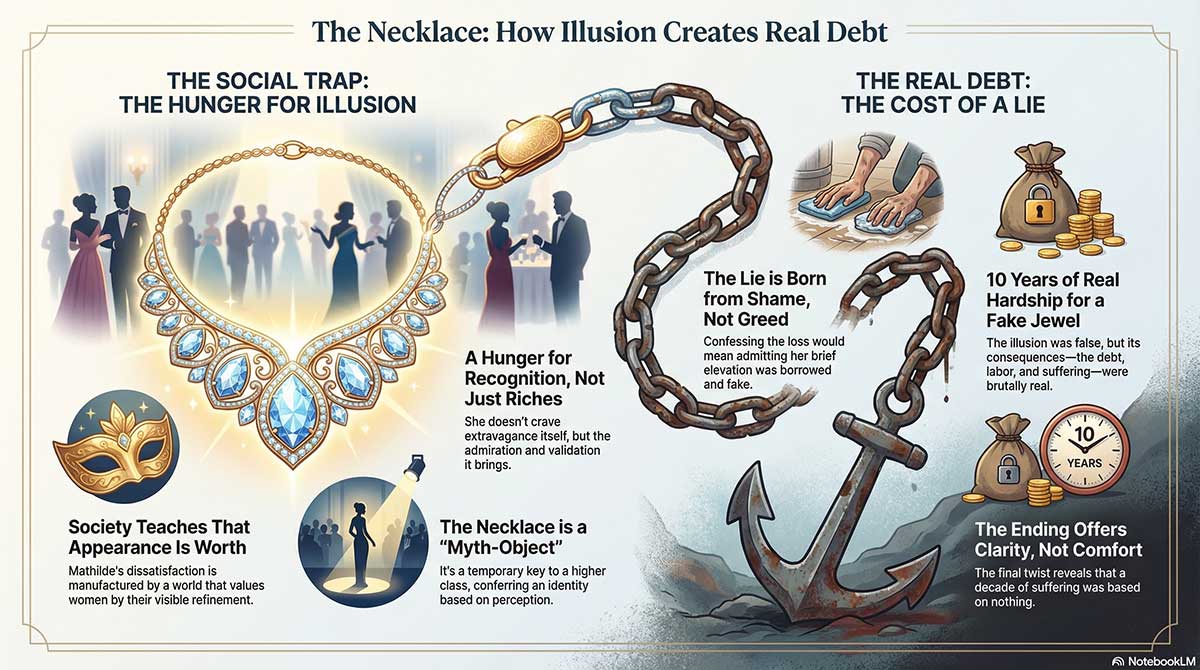

What if Guy de Maupassant discussed The Necklace with top scholars—and they proved the real “necklace” is social approval itself?

Introduction by Guy de Maupassant

I have always been accused of cruelty. Yet I do not believe life is cruel—it is simply indifferent. When I wrote The Necklace, I did not wish to punish Mathilde Loisel, nor to lecture the reader. I wished only to show how easily desire mistakes itself for destiny.

Mathilde is not exceptional. That is precisely why she matters. She does not want extravagance for its own sake; she wants recognition. She believes beauty, refinement, and admiration are proofs of worth, and society encourages her belief at every turn. The invitation, the dress, the necklace—these are not temptations imposed upon her from outside. They are answers to a question she has carried silently for years: Why was I born into the wrong life?

This story is not about a necklace. It is about the fragile agreement between appearance and value. The tragedy begins not when the necklace is lost, but when Mathilde believes that wearing it changes who she is. From that moment forward, reality merely completes what illusion has already begun.

(Note: This is an imaginary conversation, a creative exploration of an idea, and not a real speech or event.)

Topic 1: Desire, Envy, and the Invention of Identity

Wanting a life that was never yours

Moderator:

Nick Sasaki

Author:

Guy de Maupassant

Participants:

Naomi Schor

Irving Howe

Georges Lanson

Mary Donaldson-Evans

Nick Sasaki

Let’s begin with the engine of the whole story: not the necklace, not the ball, but a private feeling—Mathilde’s dissatisfaction. Is her suffering caused by poverty, or by the story she tells herself about what she “should” be?

Guy de Maupassant

Mathilde is not starving. She is haunted. Her true hunger is for a life that will confirm she matters. She looks at ordinary comfort and feels insulted by it—not because it is unbearable, but because it is not admired. That is the first trap: she mistakes visibility for destiny.

Naomi Schor

I’d add that her “story” is not purely personal—it’s social. She’s been trained to believe that a woman’s value is displayed: through dress, ornament, and the gaze of others. Her dissatisfaction is private, yes, but it is manufactured by a world that teaches her to experience herself as insufficient unless she is seen.

Irving Howe

Poverty is not the right word. It’s spiritual discontent shaped by class. She experiences her life as a kind of humiliation because she imagines an audience that is constantly judging her. The cruelty is that the audience is mostly imagined, but the social hierarchy is real. She internalizes it until it becomes self-torture.

Georges Lanson

Within the social frame of the time, her pain is perfectly legible. She is the product of a society in which class is visible, and visibility is moralized. If you look “common,” you are treated as common. Mathilde’s fantasy is not irrational—only dangerous, because it becomes the measure by which she condemns her own reality.

Mary Donaldson-Evans

And what makes it especially sharp is that she does not envy a particular person; she envies a category of existence. She wants to step into a world where effortless beauty is treated as proof of worth. That creates an identity built on external proof—fragile, addictive, and easily shattered.

Nick Sasaki

So if her longing is partly shaped by society, here’s the next step: when desire is driven by social comparison, does it ever lead to happiness—or only to perpetual humiliation?

Guy de Maupassant

Comparison rarely ends in peace. Even when Mathilde is admired at the ball, her happiness is immediate—but it is not stable. It depends on continuation. The moment she must return home, the pleasure becomes bitterness. A happiness that requires constant confirmation is not happiness; it is a loan.

Irving Howe

Exactly. The ball is an intoxication, not a transformation. Social comparison offers brief triumphs and long hangovers. It makes people chase a mirage: “Once I reach that level, I will be free.” But the ladder never ends, and each rung only reveals another rung above it.

Naomi Schor

It’s also gendered. Women are positioned to compete through signs—beauty, dress, elegance—and these signs are unstable. So the comparison doesn’t merely produce humiliation; it produces constant anxiety. Even in her moment of “victory,” Mathilde is still vulnerable, because the entire system can revoke her status in a single glance.

Georges Lanson

In realist terms, the story is almost mechanical: desire fueled by comparison produces risk, risk produces catastrophe, catastrophe produces moral revelation—if revelation is possible at all. Maupassant is showing how the social world manufactures dissatisfaction and then punishes the attempt to escape it.

Mary Donaldson-Evans

And the humiliation is internal. That’s the cruelest part. The world doesn’t need to mock Mathilde openly—she mocks herself, constantly. She becomes both prisoner and jailer, chasing approval while despising the life she actually lives.

Nick Sasaki

Final question for Topic 1: Is Mathilde’s longing shallow—just vanity—or is it a human hunger for recognition that society weaponizes?

Guy de Maupassant

I wrote her to be judged and understood at once. Her vanity is real. But vanity is often an answer to invisibility. The tragedy is that she reaches for recognition through objects, not through self-knowledge. She wants to be valued, but she mistakes the costume for the soul.

Naomi Schor

I resist calling it shallow, because “shallow” is often a moral label used to dismiss women’s suffering. Her longing is shaped by a world that gives her limited ways to feel powerful. The necklace is not simply ornament—it is access, authority, and temporary citizenship in a higher class.

Irving Howe

It’s both. She longs for recognition, but she chooses a recognition that depends on illusion. That is the moral drama: her hunger is human, but the form it takes is socially corrupt. Maupassant isn’t saying, “Don’t desire.” He’s showing what happens when desire is tethered to false value.

Georges Lanson

Realism insists on this paradox: human longing is sincere, but social routes to fulfill it are often grotesque. Mathilde’s longing is not shameful; the society that converts longing into a spectacle is what deserves critique.

Mary Donaldson-Evans

And the story leaves us with a warning: when recognition is scarce, people become desperate. They will borrow it, fake it, purchase it, and suffer for it. Mathilde’s tragedy is a human tragedy—exaggerated, yes, but frighteningly familiar.

Nick Sasaki

So the story begins before the necklace appears: it begins with a mind that has already decided ordinary life is a kind of insult. The necklace merely gives that mindset a stage.

Topic 2: Pride or Oppression?

Victimhood versus responsibility

Moderator:

Nick Sasaki

Author:

Guy de Maupassant

Participants:

Antoine Compagnon

Christopher Prendergast

Henri Troyat

Roland Barthes

Nick Sasaki

Let’s confront the question readers argue about most. Where does responsibility truly sit in The Necklace—with Mathilde’s pride, or with a social system that ranks human worth by appearance?

Guy de Maupassant

I never believed in a single culprit. Pride exists, yes—but pride is taught. Mathilde learns early that dignity has a price tag. Society whispers that worth must glitter. She listens too closely, and that is her error—but the whisper is not her invention.

Antoine Compagnon

That ambiguity is essential. If we absolve Mathilde entirely, we erase agency. If we blame her entirely, we erase structure. Maupassant stages the story precisely at that fault line where choice is real but constrained. She chooses within a narrow corridor shaped by class codes.

Christopher Prendergast

Exactly. The social world does not force her to borrow the necklace—but it makes the refusal feel unbearable. Respectability in this society is visual. To appear poor is to be judged morally wanting. Mathilde’s pride is inseparable from that judgmental economy.

Henri Troyat

From a psychological angle, pride becomes a defense mechanism. Mathilde protects herself from the pain of perceived inferiority by insisting she is meant for more. That insistence hardens into arrogance—but it begins as self-protection against humiliation.

Roland Barthes

What fascinates me is how ideology operates invisibly. Mathilde believes her desire is personal, but it is already encoded by bourgeois myth: elegance equals essence. She does not merely want status—she wants to mean something in a system that equates meaning with display.

Nick Sasaki

So let’s push this further. If society makes dignity feel purchasable, is pursuing status a moral failure—or a rational survival strategy?

Guy de Maupassant

In my world, it is often both. The tragedy is not that people pursue status—it is that status promises salvation and delivers debt. Mathilde’s mistake is trusting the promise without questioning the cost.

Antoine Compagnon

And the cost is delayed. That’s crucial. The ball rewards her immediately; the debt punishes her slowly. Systems of prestige often operate this way: quick recognition, long consequences. From within such a system, pursuit can feel rational—even inevitable.

Christopher Prendergast

We should also notice how limited her options are. For a woman of her position, advancement does not come through work or education but through marriage, appearance, and social performance. Status-seeking is not frivolous; it is one of the few available levers.

Roland Barthes

Yet ideology thrives precisely because it offers “rational” reasons to obey it. Buying dignity, borrowing elegance, performing wealth—these acts feel practical. But they reproduce the very system that withholds dignity in the first place.

Henri Troyat

Which is why Mathilde’s suffering becomes tragic rather than simply foolish. She gambles everything on a system rigged against permanence. Even success cannot last—because it was never truly hers.

Nick Sasaki

Final question for Topic 2: Does Maupassant invite us to judge Mathilde—or to recognize ourselves in her?

Guy de Maupassant

I invite judgment first—and recognition afterward. Judgment sharpens attention. Recognition unsettles it. If readers feel superior to Mathilde, the ending waits to disturb that comfort.

Roland Barthes

The story is a mirror disguised as a verdict. We condemn Mathilde for loving appearances, then realize how much of our own meaning depends on signs—brands, titles, credentials. The shock is not her mistake; it is our familiarity with it.

Antoine Compagnon

Maupassant’s realism refuses moral closure. He does not absolve her, but he also refuses to rescue the reader from implication. That tension is the ethical power of the story.

Christopher Prendergast

Yes. The narrative voice remains cool, almost indifferent. That detachment prevents sentimental pity—but it also prevents easy condemnation. We are left in an uncomfortable middle space where responsibility is shared.

Henri Troyat

And that is why the story endures. Mathilde is neither monster nor martyr. She is a person who believed what society taught her—and paid more than she could afford.

Nick Sasaki

So pride and oppression are not opposites here—they are collaborators. The system supplies the values; pride enforces them internally.

Topic 3: Silence, Shame, and the Fatal Lie

How one omission becomes a life sentence

Moderator:

Nick Sasaki

Author:

Guy de Maupassant

Participants:

Peter Brooks

Naomi Schor

Irving Howe

Henri Troyat

Nick Sasaki

Let’s turn to the pivot of the story—the moment Mathilde discovers the necklace is missing. Why is the lie so easy to begin, and why does it become almost impossible to stop once shame takes hold?

Guy de Maupassant

Because the lie is smaller than the truth—at first. To confess would be to admit not only loss, but exposure: that her brief elevation was borrowed. Silence feels manageable in the moment. The truth feels annihilating.

Peter Brooks

Narratively, this is where momentum locks in. Once the lie is chosen, the story gains irreversible direction. Plot thrives on postponement, and shame is the perfect engine—it delays confession while multiplying consequences.

Naomi Schor

Shame here is social before it is moral. Mathilde fears being seen as she truly is: a woman who dared to appear above her station. The lie protects her from immediate judgment, but it binds her to a future of punishment.

Irving Howe

And we should note how ordinary this mechanism is. People rarely lie to gain advantage alone; they lie to avoid humiliation. The story’s cruelty lies in showing how dignity, once tied to appearance, makes truth unbearable.

Henri Troyat

Psychologically, the lie becomes an identity. Once she chooses silence, Mathilde must live as someone who deserves suffering. Confession would restore proportion; silence magnifies everything.

Nick Sasaki

So is Mathilde’s decision to hide the truth an act of cowardice—or a desperate attempt to preserve identity?

Guy de Maupassant

It is both, but I lean toward desperation. Cowardice implies ease of choice. Mathilde feels cornered. To confess would collapse the fragile self she has constructed. Silence feels like survival.

Naomi Schor

And gender matters again. A woman’s reputation in this world is delicate, easily destroyed. Mathilde’s fear is not abstract—it is tied to real social penalties. The lie shields her from being reduced to ridicule.

Irving Howe

Still, desperation does not absolve consequence. The story insists that fear-driven choices can be as destructive as selfish ones. Mathilde preserves her pride—but at the cost of her future.

Peter Brooks

From a narrative ethics standpoint, the lie is the story’s moral hinge. It converts a mistake into a destiny. Without it, the tale would end quickly. With it, the story becomes tragic.

Henri Troyat

And once time passes, confession becomes harder. Ten years later, truth feels almost absurd—too late to repair anything. Silence gains weight with every year.

Nick Sasaki

Final question for this topic: Does suffering purify Mathilde into someone wiser—or does it simply break her into someone smaller?

Guy de Maupassant

I do not grant her redemption. Suffering teaches endurance, not wisdom. She becomes strong, yes—but narrowed. Hardship strips illusion, but it does not necessarily restore joy or insight.

Henri Troyat

She gains resilience but loses lightness. Her transformation is physical and moral, but not spiritual. She survives; she does not transcend.

Irving Howe

This is where readers often want consolation—and Maupassant refuses it. There is no lesson neatly learned, no moral balance restored. Only the fact that suffering is real, regardless of whether it enlightens.

Naomi Schor

And that refusal is honest. We often romanticize hardship as ennobling. Mathilde’s labor does not ennoble her; it exhausts her. That may be the story’s most unsettling truth.

Peter Brooks

Which is why the final revelation wounds so deeply. After all that endurance, the meaning collapses. The plot delivers not justice, but exposure—of time wasted, of life misdirected.

Nick Sasaki

So silence does not merely hide the truth—it reshapes a life around its absence. The lie does not end; it ages.

Topic 4: The Necklace as Symbol

Illusion mistaken for value

Moderator:

Nick Sasaki

Author:

Guy de Maupassant

Participants:

Philippe Hamon

Roland Barthes

Georges Lanson

Christopher Prendergast

Nick Sasaki

Let’s focus on the object itself. Is the necklace merely a plot device—or does it operate like a social spell that turns belief into reality?

Guy de Maupassant

It is never merely an object. The necklace concentrates desire. Once worn, it confers a temporary identity. People respond not to Mathilde, but to what the necklace signifies. Belief animates it.

Philippe Hamon

From a realist perspective, the necklace functions as a charged sign. It condenses social codes—wealth, taste, legitimacy—into a visible token. The moment Mathilde puts it on, she is read differently, and reality adjusts accordingly.

Roland Barthes

Exactly. The necklace is a myth-object. It naturalizes privilege. It makes elegance seem inherent rather than borrowed. Society collaborates by agreeing to read the sign as essence.

Georges Lanson

And historically, this is precise. In Maupassant’s France, objects mediated class. Clothing and ornament were not decoration; they were credentials. The necklace grants Mathilde access to a space otherwise closed to her.

Christopher Prendergast

Which is why its falseness is so destabilizing. If a fake object can generate real admiration and real debt, then value itself is exposed as relational—dependent on consensus rather than truth.

Nick Sasaki

So let me sharpen that: if value is decided by perception, is the necklace fake—or is society itself the fraud?

Guy de Maupassant

The necklace is honest in one sense—it does exactly what society asks of it. It convinces. The fraud lies in believing that appearance and worth are aligned.

Roland Barthes

Yes. The necklace’s “fakeness” is revealed only later, but its power was always symbolic. What matters is not authenticity, but circulation—how signs move and are believed.

Philippe Hamon

Realism often reveals that material truth is irrelevant once social meaning takes over. The necklace’s economic value is secondary to its semiotic force.

Georges Lanson

And this is why the ending stings. Readers feel betrayed, but the story insists: you believed the sign, just as Mathilde did. The revelation indicts the reader’s assumptions.

Christopher Prendergast

Society’s fraud is systemic. It teaches people to invest their lives in surfaces, then punishes them for trusting those surfaces too deeply.

Nick Sasaki

Final question for this topic: What does the necklace reveal about the difference between being admired and becoming worthy?

Guy de Maupassant

Admiration is immediate; worth is slow. Mathilde chooses the instant reward. The tragedy is not her desire for admiration, but her belief that admiration equals transformation.

Philippe Hamon

Objects can trigger admiration, but they cannot sustain identity. Once removed, nothing remains to support the illusion.

Roland Barthes

Admiration belongs to spectacle. Worth belongs to duration. The necklace offers spectacle without duration—and thus demands payment later.

Georges Lanson

Maupassant’s realism is ruthless here. The story refuses to romanticize the object. It shows how quickly admiration evaporates—and how long consequences endure.

Christopher Prendergast

In the end, the necklace teaches nothing—people do. And what they teach is devastating: worth was never granted, only borrowed.

Nick Sasaki

So the necklace does not deceive on its own. It reveals a world already willing to be deceived.

Topic 5: The Cruelty of the Ending

Irony, delayed truth, and reader judgment

Moderator:

Nick Sasaki

Author:

Guy de Maupassant

Participants:

Peter Brooks

Antoine Compagnon

Mary Donaldson-Evans

Henri Troyat

Nick Sasaki

Let’s face the moment readers never forget. Is the ending of The Necklace meant to be moral instruction, cosmic cruelty, or something colder—an exposure that refuses consolation?

Guy de Maupassant

I intended no comfort. The revelation is not punishment; it is clarity. Life does not arrange itself to be fair. It simply reveals itself—sometimes too late to repair anything.

Peter Brooks

Narratively, the ending is a shock because it collapses meaning retroactively. Ten years of suffering are instantly reinterpreted. Plot becomes judgment, not through sermon but through timing.

Antoine Compagnon

And that timing is essential. If the truth were revealed earlier, the story would become a lesson. By delaying it, Maupassant makes irony do the moral work—quietly, mercilessly.

Mary Donaldson-Evans

The cruelty lies in proportion. The punishment exceeds the “crime.” That imbalance forces readers to confront their own expectations of justice. We want suffering to mean something—and it doesn’t.

Henri Troyat

Psychologically, the ending is devastating because it offers no redemption arc. Mathilde’s endurance gains no reward, no wisdom, no compensation—only exhaustion.

Nick Sasaki

So why reveal the truth only at the very end? What does that delay do to our ethics as readers?

Guy de Maupassant

It denies relief. The reader must sit with the waste—with years lost to an illusion. Delayed truth is more violent than immediate truth.

Peter Brooks

It also implicates the reader. We participate in the illusion for most of the story. When it collapses, we are exposed alongside Mathilde.

Antoine Compagnon

Yes—this is realism’s sting. The ending refuses narrative justice. Instead, it reveals how much we rely on narrative justice to feel morally secure.

Mary Donaldson-Evans

And it forces a reevaluation of value itself. If the necklace was fake, then what was real? The labor, the debt, the aging body—those consequences are undeniable.

Henri Troyat

Time becomes the final judge. Not morality, not society—time. And time is indifferent.

Nick Sasaki

Final question: If the necklace was fake, what was real—the debt, the suffering, the transformation, or only the illusion that caused it?

Guy de Maupassant

Suffering was real. That is the only certainty. Illusions may be false, but their consequences are not.

Henri Troyat

Her transformation is real, but incomplete. She becomes tougher, not freer. The cost reshapes her, but it does not restore meaning.

Mary Donaldson-Evans

The debt is real because society makes it real. Even fake objects can command real obedience when belief is collective.

Peter Brooks

And the illusion is real too—in the sense that it governs action. Narratives, once believed, organize lives.

Antoine Compagnon

The ending leaves us with an uncomfortable truth: reality does not guarantee moral symmetry. What is real is what endures—and what endures is often pain.

Nick Sasaki

Maupassant closes the story not with justice, but with exposure. No lesson is handed down—only a question left behind: What illusions are we still paying for?

Final Thoughts by Guy de Maupassant

Readers often ask whether Mathilde deserved her fate. I find the question revealing. It suggests that suffering must be earned, that life distributes pain according to merit. I do not share this belief.

What Mathilde loses is not youth or comfort alone, but time—ten irretrievable years spent paying for a moment of borrowed splendor. And yet, those years are real. The labor is real. The exhaustion is real. Only the object that caused them was false.

That is the quiet horror I wished to leave behind: illusion can demand real payment. Society applauds surfaces, then denies responsibility when those surfaces collapse. Mathilde is not destroyed by vanity alone, but by a world that teaches her to measure herself through symbols and then abandons her to their cost.

I do not offer consolation at the end of this story. Life rarely does. I offer only clarity: what we believe about ourselves can shape our lives far more powerfully than truth—and truth, when it arrives too late, does not heal. It merely explains.

If The Necklace troubles you, it is because you recognize the debt.

Short Bios:

Guy de Maupassant — French realist master known for ruthless clarity, irony, and psychological precision; his short stories expose how social illusion quietly governs human suffering.

Nick Sasaki — Founder of ImaginaryTalks, moderator and curator of WSI conversations, blending literary scholarship with accessible, emotionally grounded dialogue for modern readers.

Peter Brooks — Influential narrative theorist whose work on plot, temporality, and delayed meaning helps explain why Maupassant’s endings strike with such lasting force.

Antoine Compagnon — Leading French literary scholar specializing in realism, irony, and modernity; widely trusted for clarifying how classic texts still shape contemporary thought.

Mary Donaldson-Evans — Prominent Maupassant scholar known for close readings of gender, class, and moral ambiguity in 19th-century French fiction.

Henri Troyat — Biographer and literary historian whose work connects Maupassant’s fiction to lived psychology, fatigue, and the erosion of idealism.

Philippe Hamon — Narrative theorist associated with realism and semiotics; examines how objects and signs (like the necklace) produce social meaning.

Roland Barthes — Seminal theorist of myth and sign systems; his ideas illuminate how appearance becomes “naturalized” as value in stories like The Necklace.

Georges Lanson — Foundational French literary historian who emphasized historical context, social structures, and reader responsibility in interpretation.

Christopher Prendergast — Scholar of French realism focusing on power, class, and irony; noted for revealing how narrative exposes social complicity rather than individual guilt.

Leave a Reply