|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

What if Faulkner’s most trusted critics walked you scene-by-scene through A Rose for Emily Explained until the ending felt inevitable?

Introduction by William Faulkner

A Rose for Emily Explained is not a verdict handed down from some clean bench of reason, but a handful of town-dust lifted and let fall again, each grain catching light for a moment before it settles back into the same old silence.

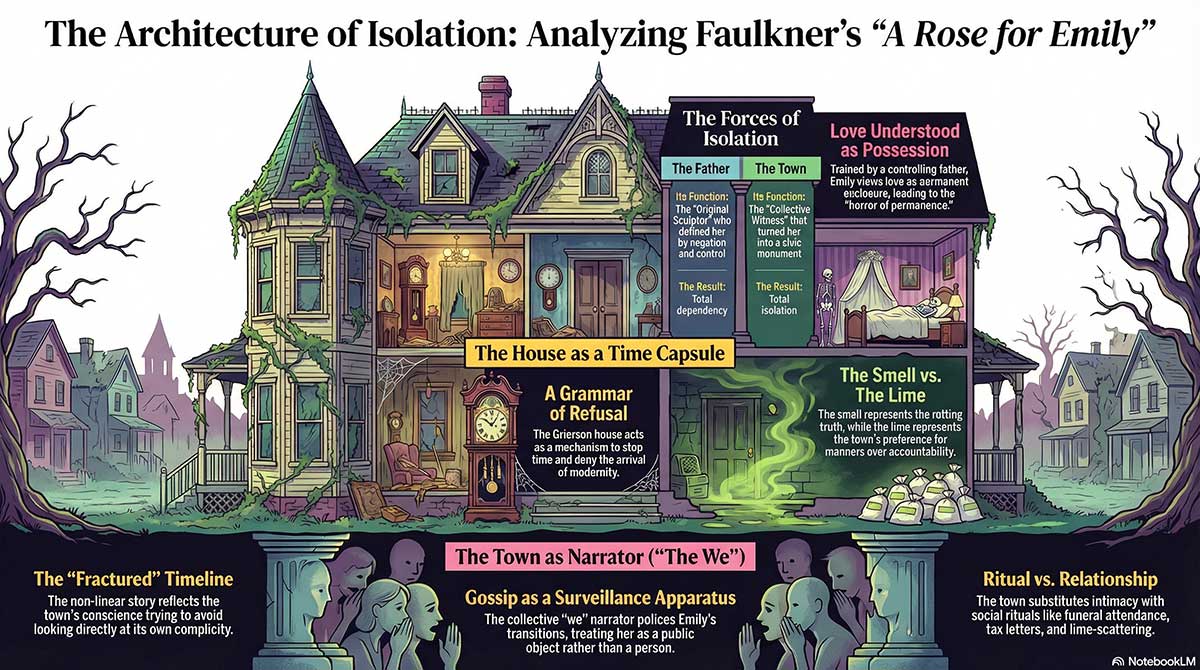

You must understand: Jefferson does not tell this tale because it loves Miss Emily. It tells it because it cannot stop watching what it helped to make. The story comes to you through a chorus—polite, curious, scandal-hungry, half-ashamed—speaking as “we,” because “we” is the easiest way to spread guilt thin enough to swallow. A town can do almost anything if no single mouth has to say, I did it.

Emily stands at the center the way an old house stands at the center of a changing street: not merely stubborn, but burdened—loaded with the weight of fathers, manners, and the ancient bargain that calls pride “dignity” and calls isolation “respect.” When the modern world arrives with its letters and taxes and bright storefronts, it does not arrive with tenderness. It arrives with rules. So she retreats into the only kingdom she has left: rooms, doors, curtains, dust. A place where time can be arranged like furniture.

And because time cannot be truly stopped—only delayed, only disguised—Faulkner’s town remembers in fragments. Not in order, not honestly, but as people remember what they cannot bear: circling the wound, naming everything except the knife. You will see the rituals: the funeral attendance that replaces intimacy, the lime scattered at night instead of a question asked in daylight, the murmurs that pretend to be concern. You will see how a community can “care” for a person so thoroughly that it never once touches her life with anything resembling love.

If there is horror here, it is not first in the locked room. It is in the long years before the door is opened—years in which everyone saw enough to know, and chose the softer sin of looking away.

(Note: This is an imaginary conversation, a creative exploration of an idea, and not a real speech or event.)

Topic 1: The Town’s “We” — Gossip, Surveillance, and Collective Judgment

Moderator: Cleanth Brooks

Panel: John T. Matthews, Philip M. Weinstein, Thadious M. Davis, Minrose C. Gwin, Jay Watson

Cleanth Brooks: Faulkner begins with a strange magic trick. He doesn’t give us Emily first; he gives us the town looking at Emily. And he doesn’t even give us an “I.” He gives us “we.” So let’s start there—what kind of creature is this narrator? Is the town simply reporting, or is it acting?

John T. Matthews: The “we” is performance. It’s the town telling a story about itself while pretending it’s telling a story about Emily. You can feel the civic posture: respectful at the funeral, proper in the tax office, discreet about the smell. But that posture is also a mask for appetite. The narrator wants access—into the house, into the secrets, into the upstairs room. The “we” claims authority by sounding communal, but it’s really a chorus of judgment.

Philip M. Weinstein: I’d push that further: the “we” is a form of protection that is also violence. Protection because it keeps Emily inside a myth—Miss Emily, the monument, the relic. Violence because that myth denies her full personhood. When a community makes you a symbol, it doesn’t have to treat you as human. Notice how the story repeatedly substitutes ritual for relationship: funeral attendance instead of intimacy, tax letters instead of honest conversation, lime at night instead of direct confrontation. The “we” is how a town avoids responsibility while still satisfying curiosity.

Thadious M. Davis: And the “we” is not innocent. It is a social machine. It decides what counts as scandal, what counts as pity, what counts as “respect.” It also decides who gets to speak and who gets turned into background. The biggest silence is not only Emily’s; it’s the town’s silence about its own systems—class, gender, race. The narrator’s “we” can feel universal, but it’s actually selective. That matters especially when you think about who is inside the “we” and who is outside it.

Minrose C. Gwin: The “we” functions like a surveillance apparatus trained on a woman’s body and choices. Emily is watched as daughter, watched as potential wife, watched as “fallen” woman when she’s with Homer, watched as oddity when she grows older. The town polices her transitions. And the collective voice lets individuals hide. No single person has to admit cruelty. The “we” dissolves accountability.

Jay Watson: There’s also a deep Southern storytelling tradition here: the communal narrator who speaks as if the whole town is a single mind. Faulkner uses that voice to show how myth gets made. The tone says: we know, we remember, we can arrange the past. But the structure betrays them—they remember in fragments, in self-serving pieces. They tell the story as if they were witnesses, but they’re often just interpreters. The “we” is how communities build a narrative that flatters their own decency.

Cleanth Brooks: Good. Now let me sharpen it. The story isn’t chronological. The town remembers in leaps, like it’s walking through a house of locked rooms. Why would Faulkner make the “we” stumble through time like that? What does this fractured ordering reveal about the town—about guilt, about desire, about self-deception?

Philip M. Weinstein: The broken timeline is the town’s conscience trying not to look straight at the center. If you told the story cleanly—arsenic, disappearance, the long isolation, the room upstairs—you’d have to face a simpler moral truth. Instead, the town narrates the past the way people narrate their own complicity: in softened fragments. The disorder becomes an alibi. “We didn’t know,” the structure suggests, even as the details imply they chose not to know.

Thadious M. Davis: Exactly. The town turns time into etiquette. Certain facts are “too direct,” so they get displaced. Think of the smell: it arrives, and instead of confronting Emily, the men sprinkle lime at night—secretly, politely, cowardly. That same impulse shapes the narrative. The chronology is a social practice: you don’t say the ugly thing first. You circle it. You sanitize it. That’s the town’s version of control.

John T. Matthews: And the circles create suspense—yes—but also authority. By controlling order, the “we” controls meaning. If the story begins with the funeral, Emily becomes a legend before she becomes a person. Then every later memory is interpreted through that legend. The narrative says: we own the frame. Emily can’t speak back, so the town’s sequence becomes her identity.

Minrose C. Gwin: I’d add that the fractured time mirrors how the town treats Emily’s life stages. They can’t allow her a normal development—daughter to woman to partner to elder. So the narration also refuses development. It freezes her, unfreezes her, freezes her again. That’s surveillance logic: she is most visible at the moments when she threatens the town’s script—when she refuses taxes, when she takes a lover, when she buys poison. The timeline is the town’s spotlight.

Jay Watson: And there’s something almost ritualistic about it. The town keeps returning to certain scenes like a congregation returning to a sermon: the father’s death, the smell, Homer, the closed house. Each return isn’t “memory” in the tender sense—it’s rehearsal. The “we” rehearses the story until it becomes a communal artifact. By the time the upstairs door opens, the town has already been practicing the ending for decades—without admitting it.

Cleanth Brooks: Let’s turn that into a verdict with teeth. Is the “we” narrator more guilty—or more helpless? In other words: are they predators feeding on a spectacle, or are they trapped in their own Southern manners and myths? And here’s the uncomfortable version: if you were in Jefferson, would you have done anything different?

Minrose C. Gwin: The town is guilty because it benefits. Even pity can be predatory when it keeps someone in a cage. They love Emily as an object: a story they can tell about the Old South, about propriety, about what happens when a woman steps outside the approved lines. Helplessness is a convenient costume.

Philip M. Weinstein: I agree, though I’d say their “helplessness” is real in one sense: they are trapped in a worldview that confuses decency with avoidance. But that trap doesn’t absolve them. The tragedy isn’t only Emily’s private collapse—it’s the town’s moral laziness, its willingness to outsource discomfort to time. “Let it pass,” they keep saying in action, and time turns that into rot.

Thadious M. Davis: And we should not ignore how systems make that laziness feel normal. The “we” voice comes from a hierarchy—who holds power, who gets excused, who gets watched. Emily is privileged in class terms, yet still controlled through gender expectations; others are erased almost completely. The town’s guilt isn’t just personal; it’s structural.

John T. Matthews: If I were in Jefferson—would I do different? That’s Faulkner’s trap for the reader. The “we” tries to recruit us. It makes us complicit by making us curious. We want the door opened. We want the reveal. And in wanting that, we start to sound like the town—polite on the surface, hungry underneath.

Jay Watson: Which brings us back to why this story lasts. It’s not simply “a Southern gothic twist.” It’s a study of communal storytelling as moral camouflage. The “we” narrator is the real haunted house. Emily’s home is only the physical copy.

Cleanth Brooks: Good. Keep that in mind as we move forward: the town doesn’t merely witness Emily—it authors her. And if the town authors her, then the final room upstairs isn’t just a shock. It’s a mirror held up to the community that kept asking, for years, to be entertained by a woman’s ruin.

Topic 2: The House as a Time-Capsule — Decay, Denial, and Southern Modernity

Moderator: Cleanth Brooks

Panel: André Bleikasten, Donald M. Kartiganer, Thadious M. Davis, Deborah Clarke, Noel Polk

Cleanth Brooks: If Topic 1 was about the town’s “we,” Topic 2 is about the most stubborn object in Jefferson: Emily’s house. Faulkner describes it like a proud old thing refusing to admit the neighborhood has changed. So let’s name it plainly—what is the house doing in the story? Is it simply setting, or is it a mechanism?

André Bleikasten: It’s a mechanism. The house is not a backdrop; it is a grammar of refusal. Every room is a sentence that says: the past is not past. Its dust, its closed doors, its smell—these are not “details,” they are the story’s way of turning time into matter. The house stores time the way a tomb stores a body: not to preserve life, but to preserve an image of life.

Donald M. Kartiganer: And psychologically, the house functions as a mind. It’s the externalized interior of Emily—compartmentalized, sealed, ritualized. The upstairs room is not just a surprise; it is the final locked chamber of a psyche that cannot tolerate loss. When reality threatens to move forward—father dead, Homer unreliable, the town modernizing—the house offers an alternative: suspend time, freeze the moment, keep the object.

Thadious M. Davis: The house also operates socially. It’s a monument the town needs. Jefferson is changing—new money, new leaders, new rules. But the house is a visible anchor for a myth: old Southern gentility. The town both resents and relies on that myth. That’s why they won’t confront her directly about the smell. They want the symbol without the mess, the heritage without the consequences.

Deborah Clarke: There’s also a gendered architecture here. Emily’s house is the “proper” place a woman is supposed to be contained in—private, domestic, quiet. But Emily’s house becomes too private, too sealed, too sovereign. The town panics not only because it can’t control what happens inside, but because the house stops performing femininity for them. It becomes a fortress rather than a parlor.

Noel Polk: I love that word—sovereign. The house is Emily’s last legal territory. Notice how often the story frames conflict at thresholds: the door where officials stand with tax notices, the doorway where the druggist must respond to her demand, the gate where townspeople try to interpret her movements. The house is where her authority can pretend to survive. Outside, time rules. Inside, Emily tries to rule time.

Cleanth Brooks: Good. Now take the story’s most humiliating detail: the smell. It’s almost comic in how the town responds—men sneaking around at night sprinkling lime like guilty teenagers. Why does Faulkner put that scene there? What is the smell “saying,” and what is the lime “saying” back?

Thadious M. Davis: The smell is truth. The lime is manners. The smell is the reality the town cannot metabolize—the physical consequence of their myth-making. They prefer deodorizing to accountability. They also choose secrecy. That choice tells us this town’s moral code is not built around justice, but around avoiding embarrassment.

Donald M. Kartiganer: And psychologically, the smell is the return of the repressed. The house is trying to seal time, but bodies don’t cooperate. Decay forces itself into the social world through the senses. The lime is a symbolic repression—cover it, don’t name it, pretend it isn’t there. That’s how denial works: a ritual performed at night.

André Bleikasten: It also deepens the story’s obsession with material time. Smell is time you cannot see. Dust is time you can. The house is full of both. Faulkner makes decay perceptible so we cannot romanticize the past. The Old South is not lace and legend; it is rot. The lime is the town’s attempt to keep the romantic story intact.

Deborah Clarke: And note how the town handles Emily’s body versus the smell. They won’t confront her. They’ll confront the odor. They will manage the symptom rather than the person. That is a form of dehumanization. Emily becomes a property problem, not a human being in crisis.

Noel Polk: Plus, the lime scene teaches us how Jefferson behaves: indirect, performative, terrified of speaking plainly. That’s the same town that says “we” while hiding responsibility. The house becomes the stage where this social choreography repeats—approach the door, retreat, gossip, intervene secretly, then congratulate yourselves for “handling it.”

Cleanth Brooks: Now let’s widen the lens. The neighborhood changes. “Garages and cotton gins” rise. New leaders appear. Emily refuses taxes. Refuses time. Refuses progress. Is Faulkner condemning her as backward, or is he condemning the modern world for having no mercy? Where does the story place its sympathy?

André Bleikasten: Faulkner refuses simple sympathy. Emily is both tragic and grotesque. The modern world is both necessary and brutal. The story’s sympathy is not a verdict; it’s a tension. The house stands as a question: what do we do with what cannot adapt? Do we demolish it and call it progress? Or do we preserve it and call it tradition? Both names can be excuses.

Thadious M. Davis: I’d say the story indicts the town most. Emily is a symptom of a social order that trained her into helpless sovereignty—privileged, protected, isolated, infantilized. Then, when that order shifts, the town wants her to update like a policy change. But they never gave her a human life to begin with. They gave her a role.

Donald M. Kartiganer: And once her role collapses, the house becomes the prosthetic that keeps her identity standing. So modernity arrives, yes—but it arrives like a demolition crew. The story doesn’t mourn the loss of the Old South as “beautiful.” It mourns the loss of anything that could have been humane within it.

Deborah Clarke: Emily’s tragedy is that her “home” becomes her only language. If the town had allowed her real relationships—friendship, community, a life beyond being watched—she might not need a house to stop time. But the only stable structure she’s permitted is domestic enclosure. So she turns enclosure into eternity.

Noel Polk: Which makes the final room feel inevitable, not merely shocking. The house is built for preservation. It preserves furniture, preserves rituals, preserves names. Eventually it preserves a body. That’s not a twist; it’s the house completing its function.

Cleanth Brooks: So here’s where we land Topic 2: The house is not just where the story happens. It is the story’s argument made wood and dust: when a culture refuses to process change honestly—when it prefers lime at night to truth in daylight—then time doesn’t pass. It ferments.

Topic 3: Love, Possession, and the Horror of Permanence

Moderator: Cleanth Brooks

Panel: Minrose C. Gwin, Thadious M. Davis, Deborah Clarke, Donald M. Kartiganer, Noel Polk

Cleanth Brooks: Topic 3 is the nerve. Homer Barron, the arsenic, the upstairs room. Readers often rush to the headline—“She killed him.” But Faulkner isn’t writing a police report. He’s writing a moral x-ray. So let me ask it sharply: is this story about love gone wrong—or about love understood as possession from the start?

Minrose C. Gwin: Faulkner makes it hard to separate those. Emily is trained to experience love as enclosure. Her father’s love—if we can call it that—functions like a wall: it keeps suitors out, keeps her “pure,” keeps her dependent. When Homer arrives, she reaches for something that looks like freedom, but the only form she knows is still ownership. So the relationship becomes a collision between desire and the only survival strategy she’s been taught.

Donald M. Kartiganer: Psychologically, the story is a study in fear of abandonment. Homer is described in a way that signals instability—charismatic, social, not naturally contained. Whether or not he intends marriage, Emily senses impermanence. And for someone whose identity is built on fixed roles—daughter of a patriarch, symbol of a class—impermanence is annihilation. The arsenic becomes the ultimate attempt to eliminate uncertainty.

Noel Polk: And notice how the town participates in that logic. They practically narrate Emily into a marriage plot. They gossip, they speculate, they “hope” she’ll marry as if it would tidy up the scandal. When she buys men’s clothing and the engraved silver set, the town reads it as a wedding inevitability—because they want the story to resolve into their preferred genre. That pressure matters. Emily is not acting in a vacuum; she’s performing under a spotlight.

Thadious M. Davis: Exactly. And that spotlight has class and gender built into it. Emily is a Grierson—she carries a decaying aristocratic authority—and she’s also a woman expected to embody restraint and propriety. Homer is Northern, working class, loud. Their pairing is not merely romance; it’s social disruption. The town’s outrage is not concern for Emily’s happiness. It’s fear of disorder. Emily is told, implicitly, that her desire is a threat.

Deborah Clarke: Which is why the story feels both tragic and horrifying. Emily’s need is understandable—companionship, stability, dignity. But the form it takes is grotesque because she has no model for mutuality. She has models for control: father over daughter, town over woman, tradition over change. So she repeats control in the only way she can guarantee it.

Cleanth Brooks: Then let’s talk about the arsenic scene—not the act, but the moment. She doesn’t plead. She doesn’t explain. She demands. The druggist asks what it’s for; she stares him down. What is Faulkner telling us about Emily’s moral posture there?

Donald M. Kartiganer: The stare is terrifying because it is sovereign. Emily’s inner world has replaced public law. The druggist becomes a bureaucratic obstacle, not a moral witness. That’s the psychology of someone who has sealed herself long enough that other people are no longer fully real. When the outside world is just noise, morality becomes private logic.

Minrose C. Gwin: And there’s gendered fury in that stare. Emily has been watched, managed, interpreted, pitied, judged. Now, for once, she acts without asking permission. It’s not framed as empowerment—Faulkner doesn’t romanticize it—but it is a moment where she refuses to be negotiated with. That refusal is one reason readers feel a strange chill: it is agency without empathy.

Noel Polk: Also, it reveals how much the town enables her. The druggist knows better. The label—“for rats”—is a wink, a dodge, a way to keep the social surface intact. Again, manners over truth. That small act of compliance is one of the story’s quiet indictments: horrors don’t only happen because someone is monstrous; they happen because ordinary people decline to intervene.

Thadious M. Davis: And we can’t ignore what kinds of authority Emily can still wield. She is isolated, yes, but she carries a class aura that makes people back away. The druggist’s compliance isn’t only fear of awkwardness; it’s deference to an old hierarchy. Even in decay, that hierarchy functions. Emily’s power is both pathetic and real.

Deborah Clarke: Which is why calling this simply a “madwoman” story misses the point. The arsenic is not only psychological; it’s social. It is what happens when a woman is taught that her worth is tied to being chosen, being contained, being respectable—and then she is left with no acceptable path to keep what she has been told she must have.

Cleanth Brooks: Now the ending. The room upstairs: a bridal tableau turned mausoleum. And the one detail that breaks the reader’s stomach—the indentation on the pillow and the iron-gray hair. What is that final image doing? Is it punishment, pity, or accusation?

Minrose C. Gwin: It’s all three, but the accusation lands on the town and the reader as much as on Emily. That hair forces intimacy into the open. The town can no longer keep Emily as a distant “monument.” The detail says: your gossip was about a real body, a real loneliness, a real extremity. You watched her for years and never truly saw her.

Donald M. Kartiganer: It’s also the story’s final statement about time. Emily’s act is an attempt to stop loss by turning love into an object. The hair shows the cost: she has lived beside death, and death has lived beside her. She doesn’t escape time—she moves into its most horrific form, where nothing changes because nothing is alive.

Noel Polk: And formally, the reveal is the town finally getting what it wanted: entry. They wanted inside the house for decades, and now they get the ultimate inside. But the “reward” is poison. The story turns voyeurism into consequence. The final room isn’t just Emily’s secret—it’s the town’s bill coming due.

Thadious M. Davis: And the bridal staging matters. It’s the warped fulfillment of the town’s marriage narrative. They wanted her married so the story would behave. She creates a marriage that cannot leave. That’s why it reads like gothic horror: it’s tradition grotesquely literalized.

Deborah Clarke: The horror is permanence. Not violence alone—permanence. Emily’s nightmare is that people leave. Her solution is to make leaving impossible. Faulkner shows us that a culture obsessed with preservation will eventually preserve what should never be preserved.

Cleanth Brooks: Then Topic 3’s verdict is this: Faulkner isn’t asking whether Emily is “good” or “evil.” He’s showing how a life trained in control and watched by a town hungry for stories can slide into a logic where love becomes possession—and possession becomes the only form of safety. The upstairs room is not just a twist. It’s a philosophy made visible.

Topic 4: Gender, Class, and the Making of a “Monument”

Moderator: Cleanth Brooks

Panel: Thadious M. Davis, Minrose C. Gwin, Deborah Clarke, Noel Polk, Philip M. Weinstein

Cleanth Brooks: By now, it’s clear Emily isn’t treated as a normal person. The town calls her a “tradition,” a “duty,” a “care,” a “monument.” That word—monument—can sound respectful, but it can also sound like a sentence. So let’s get honest: what does it mean to turn a living woman into a monument?

Philip M. Weinstein: It means you don’t have to relate to her. You relate to what she represents. A monument is public property, even if it’s built on private pain. Once Emily becomes “Miss Emily,” she is no longer allowed ordinary contradictions. The town’s language freezes her into a symbol of an older order. And when she fails to behave like a symbol—taking Homer, refusing taxes—the town reacts as if the monument has moved. That’s what disturbs them: not just the act, but the violation of the role.

Minrose C. Gwin: And notice the role is profoundly gendered. She must embody “ladyhood”—silence, restraint, purity, and dependence. The town’s outrage at her relationship isn’t simply class snobbery. It’s a panic about a woman stepping outside the choreography designed for her. They want her either protected by a father, or contained by a husband, or softened into harmless old age. The monument is a woman whose desire has been confiscated.

Thadious M. Davis: Class intensifies that confiscation. Emily’s “privilege” is real: she can refuse taxes; she can intimidate officials; she can demand poison. But that privilege is also a trap because it’s tied to a dying system. Her status depends on appearing as the last representative of “good breeding.” The town uses that appearance to soothe itself during change. So Emily’s class isn’t freedom—it’s an obligation to perform an outdated myth, and that myth requires her isolation.

Deborah Clarke: Which is why her house becomes both fortress and exhibit. The domestic sphere is where women are supposed to be safe, but here it becomes a museum where the town feels entitled to observe her life from a distance. They treat her as an artifact they can’t touch but can talk about endlessly. Even their pity is controlling: “poor Emily” becomes a story that makes the town feel humane while keeping Emily alone.

Noel Polk: And Faulkner shows how that “humane” posture turns into social negligence. The town repeatedly chooses form over care. If they truly cared, they’d have relationships with her, not rituals around her. Instead they attend a funeral, not a life. They send tax notices, not visits. They sprinkle lime, not honesty. The monument is a way to excuse inaction: “That’s just Miss Emily,” they say, and the phrase becomes a permission slip.

Cleanth Brooks: Let’s bring in the father. He stands in that famous image—Emily behind him, half-hidden, while he holds the horsewhip. The story doesn’t linger there by accident. What is the father’s function in the monument-making?

Minrose C. Gwin: The father is the original sculptor. His authority defines her by negation: not chosen, not married, not allowed. He “protects” her by refusing her adulthood. After his death, she inherits not only the house but the structure of control. The town then picks up where he leaves off. They become the new father—monitoring her respectability, managing her narrative, policing her desire.

Thadious M. Davis: Yes, and his control is also a class performance. The father’s refusal of suitors isn’t only personal; it’s about maintaining a social boundary. Emily is treated like a family asset whose “value” must be preserved. That logic is foundational to the Old South’s hierarchy. Her father’s whip is a symbol of domination that reaches beyond the family into the social order itself.

Philip M. Weinstein: Which explains why, after his death, Emily’s identity is a vacuum the town rushes to fill. She has not developed a life independent of the patriarchal frame. So she becomes a civic symbol: the last Grierson. In a sense, the town mourns the father through Emily. They keep her frozen so they don’t have to grieve the world that made him powerful.

Deborah Clarke: And she responds by performing a kind of stubborn sovereignty: “I have no taxes,” “I want arsenic,” “I will not explain.” Those are not just eccentricities; they’re her attempts to claim agency in a world that only ever gave her agency through male structures. But because she has no model for mutual freedom, her agency becomes warped into domination inside the house.

Noel Polk: That’s the story’s bitter irony. The town frames her as weak—pitiful, lonely, deluded. But the monument has teeth. She can still command deference. The tragedy is that her power is not life-giving. It is the power of refusal, the power of stopping time, the power of making a sealed kingdom where nothing can leave.

Cleanth Brooks: So here’s the hardest question of Topic 4. When readers call Emily a “victim,” they risk erasing her agency. When they call her a “monster,” they risk erasing what made her. How does the story force us to hold both without flinching?

Thadious M. Davis: By showing how systems produce extremes. Emily’s act is hers—she is responsible. But the conditions that make such an act imaginable are social: gender policing, class mythology, communal voyeurism, and the refusal to deal honestly with change. The story isn’t asking us to excuse her; it’s asking us to understand the ecosystem that made her possible.

Minrose C. Gwin: And by making the reader complicit. The narrative structure pulls us into the town’s gaze. We want the reveal. We want the locked room opened. Faulkner forces us to examine the desire to know another person’s private ruin. That’s how the victim/monster binary collapses: we’re in it, too.

Philip M. Weinstein: Emily becomes a mirror that reflects the town’s moral laziness back at it. If she is a monument, then the town built her—and then walked past her every day pretending it wasn’t responsible for the shape she took.

Deborah Clarke: Which is why the ending doesn’t feel like closure. It feels like exposure. The monument isn’t just Emily’s life; it’s the town’s values made visible.

Noel Polk: And after exposure comes the question the story never answers: what would a town look like that treats people as people, not symbols? That’s the silence Faulkner leaves us with.

Cleanth Brooks: Exactly. Topic 4’s verdict: Emily isn’t simply trapped in the past—she is manufactured by the town’s need for the past. “Monument” is the word Jefferson uses to avoid love, avoid responsibility, and avoid change. And when you turn a living woman into a monument, you shouldn’t be shocked when the monument starts behaving like stone.

Topic 5: The Ethics of Knowing — What We Watch, What We Assume, What We Refuse

Moderator: Cleanth Brooks

Panel: Jay Watson, Noel Polk, Thadious M. Davis, Minrose C. Gwin, Philip M. Weinstein

Cleanth Brooks: We end where Faulkner began: not with Emily speaking, but with a community speaking about her. The story’s final act is also the town’s final reward—entry into the locked room. So I’ll ask the question that makes the whole story burn: what is the moral difference between concern and curiosity here? When does watching become theft?

Jay Watson: Watching becomes theft the moment the watcher wants the story more than the person. Jefferson loves the narrative of Miss Emily. It gives them identity—old South, old manners, inherited dignity. Curiosity is how they keep that identity entertained. They don’t seek understanding; they seek a satisfying shape: scandal, downfall, legend, twist. And the ending delivers what gossip always wants: the ultimate private fact. The town gets what it came for, and Faulkner makes sure the prize tastes like ash.

Philip M. Weinstein: There’s an even colder edge: the town’s curiosity is a form of self-absolution. By making Emily into the spectacle, they ensure the moral center of the story stays “over there.” She becomes the container for what the community refuses to recognize in itself—its cowardice, its appetite, its hypocrisy. The locked room becomes a place where the town stores its own guilt without naming it.

Minrose C. Gwin: And the theft is gendered. Emily’s body, her relationships, her aging—these are treated as public property. The town feels entitled to evaluate whether she is respectable, desirable, broken, pathetic, shocking. That entitlement doesn’t stop when she dies; it culminates. The upstairs door opening is the final violation of privacy dressed up as communal necessity.

Thadious M. Davis: It’s also structural. The “we” narrator builds a moral world where certain people count as full subjects and others become objects of narration. That’s why the story’s ethics aren’t only about Emily. They’re about what the town’s social order permits: indirect violence, selective silence, and the tidy avoidance of responsibility. Notice the pattern: the smell happens, they lime. The taxes come, they shrug at the “tradition.” The arsenic is requested, it’s given. Again and again, the town chooses the option that keeps the surface smooth, even if the underneath rots.

Noel Polk: Faulkner makes this almost unbearable by showing that the town is not composed of cartoon villains. They are ordinary. They do what ordinary communities do when discomfort arrives: they step back, they whisper, they let time handle it. Which is precisely what makes them dangerous. A horror like the upstairs room doesn’t require a town full of monsters—it requires a town full of people who consistently choose not to know.

Cleanth Brooks: That phrase—not to know—feels central. Because the story is filled with moments where Jefferson has enough evidence to suspect something terrible, yet it chooses a kind of polite blindness. Let’s name those moments. Where does the town refuse to see?

Thadious M. Davis: The smell is the clearest. A smell that strong is a moral event. It should demand direct contact: Are you okay? Is someone dead? Do you need help? Instead, the town makes it a sanitation problem. That’s the refusal: they won’t treat Emily as a human in crisis because that would require intimacy and responsibility.

Minrose C. Gwin: And the arsenic purchase. A woman demands poison and refuses to explain—this is a scream inside a formal sentence. The druggist’s compliance is not neutrality; it is participation. The town’s ethics are outsourced to “protocol.” The protocol becomes a shield: he followed the rules, the label says “rats,” everyone can sleep.

Philip M. Weinstein: Even Homer’s disappearance is handled like a narrative gap rather than a missing person. The town’s attention is intense while the romance is public; then it becomes strangely quiet when the consequences might require action. That tells us the town isn’t committed to Emily’s wellbeing. It’s committed to the entertainment value of her deviation.

Jay Watson: And then there’s the slow, long refusal: years of isolation. A community watches a woman vanish into a house and calls it “just how she is.” That’s the deepest moral failure because it becomes normal. The town makes solitude into a personality trait so it doesn’t have to experience it as a crisis.

Noel Polk: Which leads us to the final refusal: the town never interrogates itself. It narrates Emily’s story in order to avoid narrating its own. The “we” voice is the perfect technology for that—shared voice, dispersed guilt.

Cleanth Brooks: So what does Faulkner do to the reader? Because readers, too, want the door opened. We turn pages for the reveal. Are we being indicted—or invited into compassion?

Minrose C. Gwin: Both. Faulkner indicts the reader’s appetite. He makes the ending irresistible. Then he punishes that appetite with intimacy so disturbing it can’t be consumed as mere plot. The gray hair is not there to be clever; it’s there to make the reader feel the cost of turning a life into a story.

Philip M. Weinstein: And compassion comes through the title—a rose. A rose is a gesture. It’s what you offer when words fail. The story never literally gives a rose, but the title suggests a kind of belated tenderness. The irony is that the tenderness arrives too late—after the damage, after the watching, after the sealed years. The title becomes both tribute and apology.

Thadious M. Davis: But the apology is incomplete unless the social order changes. If the town keeps operating the same way, the rose becomes performative—another ritual like the funeral attendance. Faulkner forces us to ask: are we offering Emily pity, or are we offering ourselves a way to feel decent?

Jay Watson: That’s why the story remains modern. It’s about how communities narrate “the strange one” to stabilize themselves. And it asks the most uncomfortable question: when we watch someone unravel from a safe distance, what exactly are we doing—helping, judging, or feeding?

Noel Polk: And it ends without telling us what the town learns—because Faulkner suspects it learns nothing. The house is opened, the shock is registered, the story is told. But the mechanisms that made Emily possible—avoidance, myth, surveillance—remain. The reader is left holding the rose, wondering whether it’s sympathy or indictment.

Cleanth Brooks: Then here’s our final verdict for Topic 5: A Rose for Emily is not just a gothic story about one woman’s extremity. It is a story about the ethics of attention—how a community can watch a person for decades and still refuse the one thing that might have changed everything: a direct, humane encounter. The locked room is the town’s reward for curiosity, but it is also Faulkner’s mirror held up to anyone who ever mistook watching for caring.

Final Thoughts by William Faulkner

They will say, afterward, that they were shocked. They will say it the way people speak when they want shock to stand in for responsibility. They will press into that upstairs room as if truth were a spectacle owed to them, and they will recoil as if they have discovered evil in a single woman, safely contained, safely dead, safely separate from themselves.

But the room is not separate. It is the end of a sentence Jefferson began writing long before Homer Barron ever walked its streets laughing with his workmen. It began when a father’s shadow stood between a daughter and the world; when a town decided that a woman could be either protected or pitied but never simply known; when manners became a religion and direct human contact became indecent.

The town wanted Emily to marry because marriage would make her legible. It would turn her into a story with the proper ending. When she could not be given that ending by the world, she fashioned an ending of her own—one that refuses departure, refuses loss, refuses the one law even the proud must obey: that what you love is not yours to keep.

And what is the “rose”? Perhaps it is not an excuse, not a decoration, not a sentimental ribbon tied around decay. Perhaps it is the one small thing the town did not give her while she lived: a gesture without appetite. A tribute without gossip. A mercy without conditions. Perhaps the rose is what the reader must bring—late, imperfect, and trembling—after realizing that the true scandal is not the corpse in the bed, but the years of people standing on the sidewalk, speaking softly, looking sideways, and calling that watching a kind of care.

Because the past is not dead. It is not even past. It sits in rooms we keep locked, and it waits—patient as dust—until the day we finally open the door and find, inside, not only the thing we feared, but the shape of our own refusal.

Short Bios:

Cleanth Brooks — A foundational American literary critic and leading voice in close reading, famous for clarifying how Southern writing (including Faulkner) turns form into moral pressure.

John T. Matthews — A major Faulkner scholar known for sharp work on Faulkner’s narrative methods, language, and modernism—especially how stories shape (and distort) memory.

Philip M. Weinstein — A widely cited critic of American literature whose Faulkner readings dig into moral psychology, community complicity, and the uneasy bonds between people and the stories told about them.

Thadious M. Davis — A landmark voice in Faulkner studies, especially on race, property, power, and Southern social structures—bringing the “system” into focus, not just the individual.

Minrose C. Gwin — A highly respected scholar whose work foregrounds women, gender, and interior life in Faulkner—tracking how social control becomes personal fate.

Jay Watson — A leading contemporary Faulkner critic known for lucid, teachable insights into Yoknapatawpha, Southern myth-making, and the cultural machinery behind Faulkner’s plots.

André Bleikasten — A celebrated French critic of Faulkner whose readings are prized for their elegance and depth, especially on time, decay, and the symbolic architecture of Faulkner’s worlds.

Donald M. Kartiganer — A major figure in Faulkner criticism, admired for close, psychologically attuned analysis of how Faulkner builds tension through voice, structure, and moral ambiguity.

Deborah Clarke — A strong, widely taught critic focusing on women, family roles, and the domestic sphere in Faulkner—showing how “home” can become both refuge and trap.

Noel Polk — A prominent Faulkner editor and critic deeply associated with textual scholarship and interpretation, valued for grounding big themes in precise details and language.

Leave a Reply