|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

What if the Mark Carney Davos 2026 speech got debated by the sharpest geopolitics and finance minds—no talking points, just tradeoffs?

Introduction by Mark Carney

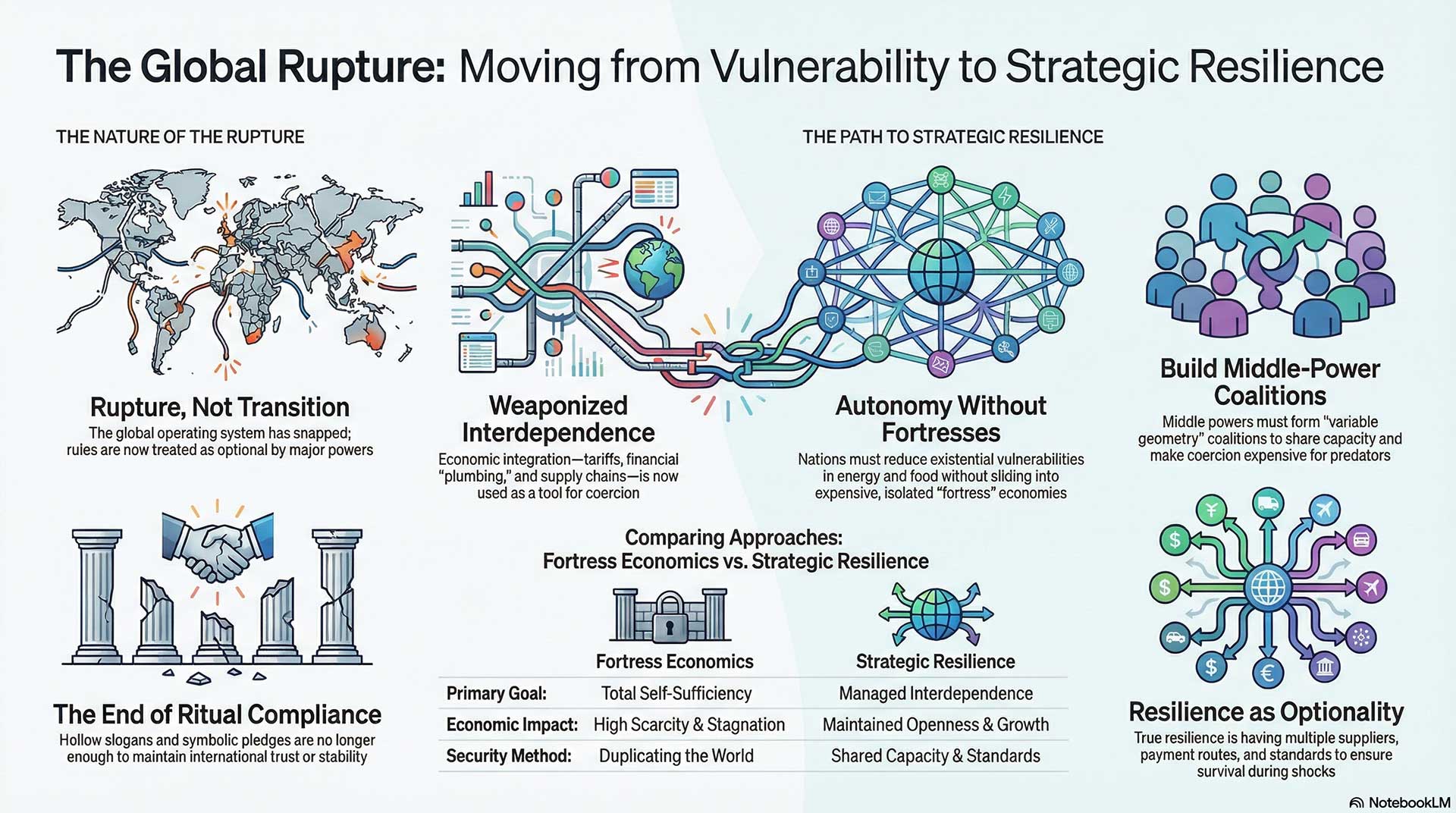

I didn’t come to Davos to offer comfort. I came to describe what many already sense: we are living through a rupture, not a transition. The old assumption—that a rules-based order would steadily widen prosperity and restrain power—has weakened to the point that repeating it can become a kind of ritual compliance. And when ritual replaces reality, we lose the ability to act in time.

In this series, I want to be plain about what that rupture looks like on the ground. Economic integration—once treated as a shared good—can now be turned into leverage: tariffs used as bargaining chips, financial infrastructure used to constrain choices, supply chains treated as vulnerabilities to be exploited. That changes how nations and businesses plan, invest, and trust.

But naming the rupture is only the start. The work is to build a practical alternative that preserves openness where it creates genuine shared benefit, while reducing the choke points that allow coercion. Strategic autonomy matters—energy, food, critical minerals, resilient finance—but a world of fortresses would be poorer, more fragile, and less sustainable. So the real task for middle powers is not to retreat, but to cooperate: to form coalitions that build shared capacity, common standards, joint procurement, and credible resilience.

If we do this well, we can live in truth without sliding into cynicism—by applying standards consistently, investing in institutions that function, and designing an interdependence that is less vulnerable to coercion. This isn’t about choosing fear. It’s about choosing responsibility.

(Note: This is an imaginary conversation, a creative exploration of an idea, and not a real speech or event.)

Topic 1: Rupture, Not Transition — Are We Past the Old World Order?

A quiet side salon off the Davos congress hall—glass walls, soft carpet, the faint hum of translation headsets even though nobody’s wearing them. Outside, snow falls like static. Inside, five people sit around a circular table under warm, flattering light that doesn’t quite manage to soften the tension.

Fareed Zakaria folds a sheet of paper once, as if to keep the room from feeling too rehearsed.

Fareed Zakaria: Mark, you used a word that changes posture: rupture. Not transition. Not turbulence. A rupture. Before anyone argues with you, I want you to define it like an engineer would. What snapped?

Mark Carney: A transition implies continuity—that the underlying operating system still works and we’re just patching it. A rupture is when the operating system itself is no longer trusted. It’s when major powers treat rules as optional, not exceptional. It’s when economic integration is no longer just mutual gain but a tool—tariffs as leverage, financial plumbing as coercion, supply chains as vulnerabilities. And it’s when middle powers discover that “going along” doesn’t buy safety; it buys temporary quiet until the next demand arrives.

Niall Ferguson: I’ll translate that into history-speak. For a while, the world benefited from a hegemon willing to pay for order—naval security, open markets, crisis firefighting. Every hegemon eventually tires of the bill. When the bill feels unfair or politically toxic, the subsidies shrink, the enforcement becomes selective, and the rhetoric turns transactional. That’s the crack. Not because rules never mattered—because the willingness to underwrite them wanes.

Christine Lagarde: I accept the diagnosis that trust is fraying. I resist the temptation to make the word do too much work. Rupture suggests a clean break; reality is messier. Institutions can weaken and still constrain. Markets still punish disorder. Inflation still bites. Capital still flees. The question isn’t only “what snapped,” it’s “what still holds.” If we announce rupture too triumphantly, we may accelerate fragmentation and turn fear into policy.

G. John Ikenberry: Both of you are right in different layers. The liberal order was never pure; it was always power plus rules plus legitimacy. The legitimacy part is what’s most damaged now. When rules are applied inconsistently, they start to look like instruments of privilege rather than mutual restraint. Then consent erodes. And without consent, enforcement becomes costly, coercive, and unstable. Rupture is not merely the end of a system—it’s the end of belief in a system.

Graham Allison: I’m less interested in the poetry of rupture than the mechanics of danger. Great-power rivalry is structural. When leaders believe core interests are at stake—security, regime stability, technological dominance—they take risks. The snap happens when each side assumes the other will blink, and the price of miscalculation shrinks in their imagination. Whether you call it rupture or transition, the hard part is designing guardrails when the political incentives favor escalation.

A brief silence lands. Fareed lets it.

Fareed Zakaria: So let’s step into the uncomfortable middle. If rules don’t bind great powers consistently, what does? What actually prevents a slide into pure coercion?

Graham Allison: Fear of catastrophic consequences. Deterrence is not a slogan; it’s a system of credible capabilities and credible will. What binds is the expectation of unacceptable loss—military, economic, political. The problem today is that leaders increasingly believe they can absorb losses. That’s when coercion becomes tempting.

Christine Lagarde: Constraints bind. Not only military ones. Economic ones. A country can talk as if it is sovereign from markets, but even great powers face inflation, debt dynamics, demographic pressures, and growth limits. The trick is to strengthen domestic credibility—independent institutions, stable fiscal paths, reliable frameworks—so you’re harder to coerce and less likely to lash out. Coercion thrives where vulnerability is obvious.

Mark Carney: And vulnerabilities are now designed into interdependence. What binds great powers less than before is the belief that integration is a shared good. When integration becomes a bargaining chip, binding shifts to leverage. That’s precisely why middle powers can’t be passive. They need resilience—diversified supply chains, energy security, financial optionality—and, crucially, coalitions. Binding can come from collective capacity: if coercion against one triggers coordinated costs from many, coercion becomes less attractive.

G. John Ikenberry: I’d add legitimacy as a binding force, even for the powerful. When a great power loses legitimacy, it pays a “trust premium” on everything—alliances become brittle, intelligence sharing narrows, technology partnerships slow, capital costs rise, and soft power evaporates. You can bully for a while. But long-term influence depends on being seen as predictable and fair enough that others choose alignment rather than merely endure it.

Niall Ferguson: You’re all describing constraints, but remember: constraints are uneven. Some regimes can tolerate inflation and isolation in ways democracies struggle to. Some leaders can absorb reputational damage because they don’t rely on international legitimacy for domestic survival. So what binds? Sometimes very little—until you hit a wall. And walls in history tend to arrive suddenly. The danger is assuming the wall is far away when it is, in fact, right in front of you.

Fareed’s eyes flick briefly to Carney, like he’s testing whether “rupture” still matters after this.

Fareed Zakaria: Last move. Suppose we accept that we’re in a new phase where coercion is on the table. What replaces the old order: a rebuilt system, regional blocs, permanent volatility? And for middle powers—what do you actually do besides issuing communiqués?

G. John Ikenberry: A rebuilt system won’t look like the old one. It will be more plural, more conditional, more regional—but it can still be rule-based in key domains: trade dispute mechanisms, standards, climate accounting, arms control frameworks, tech governance. Middle powers can be architects if they insist on reciprocity and real voice. The replacement isn’t “one order” so much as a scaffolding of partial orders that reduces chaos.

Mark Carney: I think the likely near-term reality is a patchwork. So the task is to shape the patchwork so it doesn’t become a world of fortresses—poorer, more fragile, less sustainable. Middle powers need “variable geometry” coalitions: align where interests overlap, build shared resilience, bridge blocs where possible rather than choosing permanent camps. Make coercion expensive through collective action. And make autonomy credible without turning inward.

Niall Ferguson: Historically, new orders follow settlements, and settlements often follow shocks. If we’re honest, we’re in the pre-settlement era. That’s the messy stretch where everyone pretends they can have the benefits of globalization without the vulnerabilities, and the security of alliances without paying for them. Middle powers should prepare for shocks—financial, military, technological—and build redundancy. Not because redundancy is efficient, but because fragility is fatal.

Christine Lagarde: If you overcorrect into fortress economics, you institutionalize scarcity. The replacement must preserve openness where it supports prosperity, and build autonomy where vulnerabilities are existential. That requires discipline—choosing priorities instead of promising everything. For middle powers, credibility is power: consistent policy, investable frameworks, and the capacity to cooperate across borders without surrendering your values.

Graham Allison: Permanent volatility is the default unless we design against it. That means guardrails: crisis hotlines, arms control in new domains, deconfliction in cyberspace and space, rules for export controls, and norms for economic retaliation. Middle powers can help by convening, by proposing workable mechanisms, by refusing to let every conflict become total. The replacement order is less a grand treaty and more a set of restraints that prevent a bad day from becoming a catastrophe.

Fareed closes his paper again, as if returning it to the future.

Fareed Zakaria: So, Mark, your word “rupture” is less a forecast than a demand: stop waiting for the old script to return, and start building the constraints, the coalitions, and the credibility that make coercion harder.

Mark Carney: Exactly. “Transition” encourages spectators. “Rupture” forces builders.

The room doesn’t applaud. In Davos, applause can feel like self-congratulation. Instead, there’s something better: a quiet recalibration—people mentally redrawing maps, not of borders, but of dependencies.

Topic 2: Integration as Weapon — Tariffs, Finance Rails, and Supply Chains as Coercion

A different room this time—still Davos, but not the plush “vision” lounge. This is a glass-walled briefing suite with a long table, tight chairs, and that unmistakable smell of printer toner and espresso. Outside, the promenade glitters with badges and ambition. Inside, the mood is more like air-traffic control.

Gillian Tett sits at the head with a thin folder—mostly blank pages, because everyone here already knows the data. What they don’t know is what the data means now.

Gillian Tett: We’ve spent three decades celebrating interdependence like it was a moral achievement. Mark, in your speech you flipped it: interdependence can become leverage—tariffs, finance rails, supply chains. Let’s get specific. Where is the line between legitimate national security and outright economic coercion? And who has the authority to draw that line when the strongest actors can simply ignore it?

Robert Lighthizer: The line is drawn by states—full stop. “Authority” isn’t an abstract tribunal; it’s the reality of power and responsibility. If a country believes a supply chain dependency can cripple its defense capacity or its industrial base, then it’s not just an economic issue—it’s a security issue. The problem with the old framing is it treated trade as neutral and politics as the distortion. In real life, trade has always been policy. Coercion? Sometimes. But pretending you can separate economics from national interest is how you end up dependent in the first place.

Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala: Security is real, but “security” becomes dangerous when it expands without limits. The line must include proportionality, transparency, and a clear connection to the threat. If measures are open-ended, vaguely justified, and used to extract unrelated concessions, that is coercion. And yes—enforcement is hard when power is uneven. But rules are not pointless because they are sometimes violated; they are essential because without them, smaller and vulnerable economies become the battlefield by default.

Eswar Prasad: I’d add a practical test. When a policy is narrowly targeted, time-bound, and subject to oversight, it looks like security. When it’s broad, indefinite, and selectively applied, it looks like coercion. And there’s a second dimension: the quiet forms of coercion—the “plumbing.” Payment rails, correspondent banking, compliance regimes. These don’t announce themselves as weapons, but they can shape behavior more effectively than tariffs because they operate in the shadows of risk management.

Adam Tooze: The line is politically constructed, which is exactly why it’s so unstable. We talk as if there’s a neutral distinction, but security and economics have fused into a single arena of strategic competition. “Who has authority?” Often the actor controlling the chokepoint—shipping insurance, dollar clearing, export licensing, cloud infrastructure. This isn’t a moral argument; it’s an architectural one. The global economy is not a free-floating market. It’s a designed system, and design implies control.

Mark Carney: The simplest way to see the line is intent and effect. Security policy reduces a clear vulnerability with minimum collateral damage. Coercion uses interdependence to compel behavior beyond the immediate risk—often by raising uncertainty and fear. But I’ll say something uncomfortable: the line is becoming harder to enforce because trust is eroding. That’s why middle powers can’t rely on rhetorical commitments. They need resilience and coalitions that make coercion costly.

Gillian nods, then steeples her fingers like she’s about to push them off the polite cliff.

Gillian Tett: If tariffs, finance rails, and supply chains can be switched on and off, are we inevitably headed toward fragmentation—competing systems, competing standards, competing payment networks? Or can we build guardrails that keep interdependence from turning into hostage-taking?

Eswar Prasad: Fragmentation is already happening at the margins, but total fragmentation is expensive. Trust at scale is hard to replicate. The risk is partial fragmentation: multiple systems that don’t fully interoperate. That raises transaction costs, amplifies uncertainty, and increases the chance of accidents—especially in crises. Guardrails are possible, but they require at least minimal shared norms: when sanctions are used, how they’re communicated, what off-ramps exist, what counts as escalation.

Adam Tooze: The deeper point is that “guardrails” compete against domestic politics. Guardrails require restraint, and restraint is rarely rewarded in election cycles or power struggles. Once leaders discover economic tools can deliver quick wins—signal strength, punish rivals, satisfy constituencies—those tools become habit. Interdependence then feels like threat, and the political demand becomes: “reduce exposure,” even if it costs prosperity. That is how you drift into blocs without ever officially choosing them.

Robert Lighthizer: I’m less sentimental about fragmentation. A system that made countries dependent on rivals for critical goods wasn’t “efficient,” it was reckless. Competing systems can be stabilizing if they reduce any single actor’s ability to dictate terms. The guardrail is capacity: build your own, build with allies, and you won’t be vulnerable to pressure. The idea that we can simply return to a world where everyone plays fair because it’s better for GDP—that’s the illusion.

Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala: Competing systems may feel like safety to large powers, but they are punishing for everyone else. Smaller economies cannot comply with three sets of standards, three payment architectures, and three sets of export controls. That becomes a tax on development. Guardrails must exist, or the world becomes less prosperous and more unstable. It’s not about nostalgia—it’s about preventing economic conflict from becoming the default language of geopolitics.

Mark Carney: We should assume some reconfiguration is inevitable. But there’s a difference between strategic resilience and fortress economics. If every country duplicates everything, you end up with a poorer, more fragile world. Guardrails can be built through issue-by-issue agreements—shared standards, transparency around restrictions, coalitions that keep trade and finance functioning where possible, even while security competition persists. The goal is not naïve openness; it’s managed interdependence with fewer choke points.

Gillian flips the folder closed, as if to signal: now we stop theorizing.

Gillian Tett: Let’s get brutally practical for the middle powers and the companies listening. What resilience is real—diversification, friend-shoring, stockpiles, industrial policy, alternative payment routes? And what’s the move that sounds smart in speeches but backfires in reality?

Adam Tooze: The backfire move is promising certainty. Leaders sell “resilience” as if it’s an endpoint: build a factory, sign a pact, and you’re safe. Real resilience is governance—constant mapping of exposure, ongoing investment in redundancy, and the political capacity to absorb shocks without panic. The speech-friendly version of resilience becomes expensive theater if the state lacks the administrative muscle to execute it.

Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala: Real resilience starts with diversification and transparency—know your dependencies, reduce single points of failure, and cooperate where the costs of duplication are too high. The backfire move is blanket protectionism. If every sector becomes “strategic,” you end up subsidizing everything, breeding inefficiency, and triggering retaliation. That spiral makes everyone less secure, not more.

Robert Lighthizer: Real resilience is domestic capacity in strategic sectors and trusted alliances in the rest. The backfire move is continuing to rely on rivals for critical inputs because “it’s cheaper.” Cheap is not a strategy. Another backfire: assuming institutions will protect you while you remain exposed. They won’t—not when the pressure rises. Build leverage or accept vulnerability.

Mark Carney: Real resilience is optionality—multiple suppliers, multiple routes, multiple partners—and the ability to say no without being crushed. It’s also coalitional: shared stockpiles, joint procurement, common standards, and investments that reduce choke points. The backfire move is fortress economics—trying to pull everything home, duplicating the world. That turns resilience into stagnation and makes conflict more likely because scarcity becomes political fuel.

Eswar Prasad: Real resilience is not only physical supply chains; it’s financial and digital plumbing. Companies obsess over sourcing and ignore payment disruptions, sanctions exposure, data jurisdiction, and cyber vulnerabilities. The backfire move is building a “resilient” supply chain that collapses the moment banking channels tighten or compliance risk spikes. In this era, resilience requires scenario planning across money, data, and logistics—not just containers and factories.

Gillian looks around the table like she’s taking a measurement: not of their optimism, but of their willingness to pay for what they’re recommending.

Gillian Tett: So the paradox is clear. The more interdependence becomes leverage, the more everyone hedges. And the more everyone hedges, the more the world feels like a series of potential choke points.

For a moment nobody reaches for the easy closing line. Davos doesn’t need another slogan.

Mark Carney finally says it quietly, almost like a reminder rather than a conclusion: “Keep the benefits of integration—remove the choke points.”

No one argues. Not because they agree on everything—but because everyone in the room understands the same thing: the era of innocent interdependence is over, and the bill for resilience has arrived.

Topic 3: Strategic Autonomy vs Fortress Economics — How Much Self-Reliance Is Enough?

The next morning, the snow is brighter—almost aggressive. Davos looks clean, like a world that never makes mistakes. Inside the conference center, Martin Wolf chooses a smaller room with worse chairs and better honesty. He wants fewer speeches and more arithmetic.

A single phrase is written on a blank card at the center of the table:

“AUTONOMY WITHOUT FORTRESSES.”

Martin Wolf: Everyone here agrees on the diagnosis: vulnerabilities exist, coercion is real, and dependence can be weaponized. But the proposed cure—strategic autonomy—can become its own disease. Mark warned about a world of fortresses: poorer, more fragile, less sustainable. So let’s do this properly. How much self-reliance is enough? What must be sovereign, and what must remain global if we want growth, innovation, and stability?

Fatih Birol: Energy is the first place where reality punishes ideology. A nation without reliable energy is not autonomous; it’s exposed. But energy autonomy doesn’t mean isolating from markets. It means diversified supply, resilient grids, storage, and domestic capacity where it matters—refining, critical materials, and infrastructure. If you try to do everything alone, you pay too much. If you rely on one supplier, you risk everything.

Dani Rodrik: I’d separate “sovereignty” from “self-sufficiency.” Sovereignty is the ability to pursue your domestic priorities without being vetoed by external pressure. Self-sufficiency is producing everything at home. The first is necessary; the second is usually wasteful. The question is: which domains are so politically and socially essential that losing them would threaten the state’s legitimacy? Food security. Energy reliability. Certain health and defense capabilities. Beyond that, you design smart interdependence.

Larry Summers: And we should be honest about cost. Strategic autonomy—if done broadly—means higher prices, lower productivity, and slower growth. You can justify some of that as insurance, but not unlimited insurance. We’re at risk of calling everything “strategic” because it’s politically convenient. The moment you label every industry vital, you hand out subsidies like candy and wonder why your economy stops innovating.

Mariana Mazzucato: That framing assumes the only choice is “efficiency” versus “waste.” Autonomy can be mission-oriented investment, not just defensive duplication. The state can shape markets, build capabilities, and crowd-in innovation. The real danger is not industrial policy; it’s bad industrial policy—captured, unaccountable, lacking clear missions. If you invest with purpose—clean energy, resilient health systems, strategic technologies—you can create new growth, not just reduce risk.

Mark Carney: We keep circling the same tradeoff: vulnerability versus stagnation. My point is not “retreat.” It’s design. Strategic autonomy should reduce choke points without turning into fortress economics. The world of fortresses—everyone duplicating everything—would be poorer, more fragile, less sustainable. So we need shared resilience: trusted partnerships, common standards, collective procurement. Autonomy plus cooperation.

Martin Wolf nods once—like a judge granting that everyone has made their opening statement.

Martin Wolf: Good. Now the second question, and I want it answered with uncomfortable specificity. How do you pay for autonomy without triggering inflation, rent-seeking, and permanent subsidy dependence? In other words: how do you avoid creating a political economy where “strategic” becomes a blank check?

Larry Summers: Discipline. Rules. Sunset clauses. If a subsidy cannot justify itself with measurable outcomes, it expires. And if you can’t name the objective—resilience against what threat, by what date, with what metric—you shouldn’t fund it. The trouble is that industrial policy becomes a way to hide fiscal giveaways. Autonomy becomes a slogan that launders inefficiency.

Mariana Mazzucato: I agree on metrics, but I reject the idea that the state can’t invest boldly. The solution is governance, not timidity: transparent missions, conditionalities, public returns—equity stakes or royalties when public investment creates private gains. Otherwise taxpayers fund innovation and investors harvest it. Autonomy spending must build public value, not just corporate balance sheets.

Dani Rodrik: And we must accept that autonomy is a political project. It must be legitimate. People will support higher costs if they believe the gains are real and shared. That means investing in workers, not only firms. It means regional development, training, and social protection. If autonomy is perceived as elite protectionism, it will fail politically—then you get whiplash policy, which is the opposite of resilience.

Fatih Birol: Energy illustrates the risk: you can spend enormous sums on capacity and still fail if permitting is broken, grids aren’t upgraded, and supply chains for materials are fragile. Paying for autonomy isn’t just money; it’s institutional competence—planning, regulation, speed. Inflation comes from bottlenecks. Solve bottlenecks, and the cost curve changes.

Mark Carney: I would add coalition economics. If like-minded countries coordinate procurement and standards, you reduce the duplication tax. A buyers’ club for critical minerals, shared strategic stockpiles, interoperable grids—these reduce cost and increase bargaining power. Autonomy alone is expensive. Autonomy together is cheaper and more credible.

Martin Wolf’s eyes brighten slightly. This is the part he enjoys: the moment everyone realizes “autonomy” isn’t a poster; it’s a balance sheet.

Martin Wolf: Final question. What metric tells us autonomy worked? Because if we measure it wrong, we’ll spend trillions to feel better. Are we optimizing for fewer coercion points? Faster crisis recovery? Lower volatility? Higher long-term growth? What’s the KPI that matters?

Fatih Birol: For energy, the KPI is reliability under stress. Can the system keep lights on and factories running during shocks—war, embargo, extreme weather? Diversification and storage are measurable. Grid resilience is measurable. If you still face blackouts or price spikes that destabilize society, autonomy has failed.

Dani Rodrik: For me, the KPI is policy space. Can a country make domestic choices—labor standards, climate goals, public health measures—without facing an external veto through capital flight, trade retaliation, or supply strangulation? Autonomy is freedom to govern, not merely domestic production.

Larry Summers: I’d keep it simple: cost-adjusted resilience. If you gain marginal security at massive economic cost, you’re poorer and not necessarily safer. So measure the reduction in catastrophic downside risk relative to the drag on growth. A little drag is fine. A lot becomes self-harm.

Mariana Mazzucato: I’d measure capability building. Did you create new productive capacity, new innovation ecosystems, new public-private collaboration that can pivot in crises? If autonomy investment becomes a platform for future growth and transformation, then it isn’t just insurance—it’s development.

Mark Carney: I’d combine them: fewer choke points, faster recovery, and sustained prosperity. And I’d add one more: sustainability. Autonomy that relies on fossil dependence, ecological damage, or inequality is unstable. The goal is resilience that endures—economically, politically, environmentally.

Martin Wolf leans back, and for a second the room feels less like a debate and more like a design studio.

Martin Wolf: So the real argument isn’t whether we need strategic autonomy. We do. The argument is whether we can build autonomy without building scarcity, without building corruption, and without building a world where every nation walls itself in and calls it security.

He turns to Carney.

Martin Wolf: Mark, one sentence to end this: what is the central discipline that prevents “autonomy” from becoming “fortress”?

Mark Carney: Cooperation that reduces choke points—without duplicating the world.

Outside, the snow keeps falling. Inside, the room feels a little warmer—not because the world is safer, but because the tradeoffs are finally being spoken plainly.

Topic 4: Middle-Power Coalitions — “If You’re Not at the Table, You’re on the Menu”

The room for this one is smaller, sharper—less “summit,” more “war room.” A circular table, five microphones that nobody really needs, and one screen on the wall showing nothing but a quiet world map—no labels, no headlines, just continents like a reminder: this isn’t theory.

Ian Bremmer looks around like he’s counting not people, but incentives.

Ian Bremmer: Mark, you keep coming back to one line that lands because it’s ugly and true: if you’re not at the table, you’re on the menu. Let’s make this practical. When a middle power says “coalition,” what does that actually mean in the real world—what gets built, what gets signed, what gets funded?

Mark Carney: “Coalition” can’t mean applause lines and communiqués. It means shared capacity. Joint procurement of critical inputs. Common standards that reduce friction and prevent coercion through compliance traps. Coordinated investment—especially where scale matters: grids, storage, critical minerals processing, secure digital infrastructure. It also means bridge-building between blocs where possible, because a world that hardens into fortresses becomes poorer, more fragile, less sustainable.

Stephen Walt: Coalitions are not friendships; they’re transactions wrapped in strategy. The most reliable coalitions are built on clear threat perceptions and clear commitments. If middle powers want something durable, they need to define the threat, define the mutual obligations, and accept that free-riding destroys trust. What you “build” is credibility: mechanisms that make promises costly to break.

Anne-Marie Slaughter: I’d add that coalitions today succeed less through one grand treaty and more through dense networks. Think interoperable standards, shared data protocols, mutual recognition agreements, joint training, professional exchanges—so the system is resilient because it’s braided. The funding piece matters, but so does the connective tissue: relationships between regulators, engineers, financiers, civil society leaders. That’s what makes “variable geometry” coalitions real instead of rhetorical.

Dambisa Moyo: Coalitions often sound like a club for wealthy countries deciding the rules. If middle powers want legitimacy, they have to include development realities: access to finance, infrastructure, and fair terms for resource-producing nations. A buyers’ club for critical minerals can look like cooperation—or it can look like cartel behavior from the consumer side. What gets built must include investment and value-add in producer countries, or you’ll trigger backlash and instability.

Kishore Mahbubani: Middle powers should stop thinking in moral slogans and start thinking in strategic balance. Coalitions work when they provide something tangible: market access, technology transfer, stability, predictable supply. The “build” is optionality. A middle power’s strength is not dominance—it’s flexibility. Coalitions should expand room for maneuver, not shrink it into permanent alignment with one camp.

Ian Bremmer nods once, satisfied that nobody tried to answer with poetry.

Ian Bremmer: Good. Now let’s walk into the hard part. Can coalitions be values-based and durable—or do they inevitably become transactional, temporary, and a bit hypocritical? In other words: are “shared values” glue, or just branding?

Stephen Walt: Values can help, but interests are the glue. If values are aligned with interests, great—coalitions feel legitimate and people cooperate more easily. But when values conflict with interests, values will lose more often than people admit. The danger is pretending values are the driver when they’re not; that creates disappointment and brittle alliances.

Anne-Marie Slaughter: I think values are real—but they need institutional expression to survive stress. Rule of law, transparency, accountability: those aren’t just moral ideals, they’re operating principles that make cooperation trustworthy. Values-based coalitions become durable when they create predictable behavior—when you know your partner won’t weaponize the relationship at the first domestic political shift. That said, “values” can’t be used as a gatekeeping tool; they must be paired with humility and practical commitments.

Kishore Mahbubani: Values-based talk often masks status. The world is not divided neatly into virtuous and non-virtuous camps. If middle powers want influence, they should practice what I call pragmatic consistency: cooperate where you can, compete where you must, and avoid turning every disagreement into a moral crusade. Durable coalitions are built on respect—especially respecting that other societies will not mirror your model.

Mark Carney: Values matter because they define what you’re trying to preserve: dignity, fairness, the idea that power should be restrained by norms. But I agree that values must be pragmatic—values-based realism. If coalitions are purely transactional, they won’t hold under pressure. If they’re purely values-symbolic, they won’t work in the real world. The point is to build coalitions that deliver security and prosperity in ways consistent with the standards you claim.

Dambisa Moyo: Here’s the uncomfortable truth: values rhetoric has been applied selectively, and many countries remember that vividly. Durability comes from mutual benefit and credibility. If coalitions want legitimacy, they must deliver development gains—not just security gains for the already-secure. If a coalition’s “values” translate into restrictions, compliance costs, and constrained financing for poorer nations, it won’t be seen as values—it’ll be seen as control.

Ian lets that sit. The silence in the room is not awkward; it’s analytic.

Ian Bremmer: Last question, and it’s the one everyone dances around. Mark says middle powers need leverage so they can say “no” without being punished. What leverage should they build, specifically? And what are they willing to trade to get it?

Dambisa Moyo: Leverage is resources plus governance. If you’re a producer nation, your leverage is minerals, energy, land, demographics—but you only convert that into power through stable contracts, predictable policy, and infrastructure. Middle powers should build leverage by moving up the value chain: refining, processing, manufacturing components—not just exporting raw inputs. The trade is openness: you may need to offer market access or regulatory alignment in exchange for investment and security guarantees.

Mark Carney: Leverage is resilience. Energy security—reliable supply and diversified routes. Financial resilience—payment optionality, credible institutions, deep capital markets. Supply resilience—multiple suppliers and domestic capability where chokepoints are existential. And coalition leverage—shared procurement and standards that make coercion harder. The trade is real: you may have to coordinate policy more tightly, accept common rules, and invest up front for collective benefit.

Kishore Mahbubani: A middle power’s leverage is strategic positioning—being indispensable to multiple sides without being owned by any. That means being a credible partner: stable, predictable, competent. It also means not overcommitting to one bloc’s narrative. The trade is sometimes emotional: you’ll disappoint allies who want loyalty theater. But the reward is strategic autonomy.

Stephen Walt: Leverage is also military and intelligence capacity—enough to matter, enough to contribute, enough that allies take you seriously. If you want to be at the table, you pay some of the bill. The trade is domestic: higher defense spending, political risk, and hard choices about what you prioritize. Coalitions respect contributors, not spectators.

Anne-Marie Slaughter: Leverage can be institutional as much as material. If you host standards, shape tech governance, build trusted digital infrastructure, and become a hub for talent and ideas, you gain influence that doesn’t depend on coercion. The trade is openness with guardrails: welcoming talent, investing in education, protecting rights, and building public trust so your society can sustain the strategy.

Ian glances at the blank world map, then back at the faces.

Ian Bremmer: So the real coalition test is not whether we can draft a statement. It’s whether we can build shared capacity fast enough that coercion stops being cheap.

Mark Carney: Exactly. Coalitions fail when they’re performative. They succeed when they make predation expensive.

Dambisa Moyo: And when they make development real—not promised.

Stephen Walt: And when members actually pay.

Anne-Marie Slaughter: And when the network holds under stress.

Kishore Mahbubani: And when they respect the world as it is, not as they wish it to be.

Outside, the snow keeps falling. Inside, the table feels less like a panel and more like a blueprint—unfinished, expensive, and suddenly unavoidable.

Topic 5: “Live in Truth” — Havel’s Greengrocer and the End of Ritual Compliance

A quiet corner in Davos—late, after the panels and the handshakes. The room is glass and wood and soft light, like an upscale reading lounge that wants to pretend it’s above politics. Outside, snow drifts against the window. Inside, the air feels electrically still.

On the table sits a small prop someone brought as a joke that turned serious: a miniature storefront sign in a blank frame. No words. Just the shape of a slogan.

Zanny Minton Beddoes watches the group settle—five figures, five different instincts, one shared unease: the sense that the world is entering an era where people keep repeating the rituals… but fewer and fewer believe them.

Zanny Minton Beddoes: Let’s begin with Havel’s greengrocer—the person who hangs a slogan in the window not because they believe it, but because it keeps them safe. If our age is drowning in “ritual compliance”—corporate DEI slogans nobody follows, climate pledges without budgets, diplomacy with no enforcement—what does “live in truth” actually look like now? Not as poetry—as an action.

Mark Carney: “Live in truth” begins with pricing reality and telling the truth about tradeoffs. When we pretend we can have resilience without cost, net-zero without investment, security without coordination, we invite cynicism. The action is measurable commitment: publish the metrics, fund the plan, accept accountability. In markets and governments, trust is built when promises are tied to consequences. Ritual compliance dies when leaders stop rewarding it—when they stop treating the appearance of virtue as the same thing as results.

Václav Havel: The greengrocer’s tragedy is not cowardice—it is loneliness. He believes he is alone in his disbelief. “Live in truth” is a small act that breaks the spell of loneliness. It might be refusing to sign a lie. It might be speaking plainly in a meeting where everyone is using fog. The action is not “heroic rebellion” every day. It is choosing not to participate in the theater of falsity—and accepting the social cost. When one person withdraws their ritual compliance, it exposes the ritual as optional. The regime—any regime of lies—depends on the feeling that everyone has agreed.

Anne Applebaum: Today’s ritual compliance is often voluntary—and algorithmic. People perform belief to stay inside a tribe, inside a career, inside a social network. “Living in truth” now means refusing to join the manufactured unanimity. Concretely: institutions must protect dissenters. Journalists must stop laundering euphemisms. Leaders must name coercion when it’s coercion, corruption when it’s corruption, propaganda when it’s propaganda. The action is precision: vocabulary that punctures the fog.

Maria Ressa: In the digital world, ritual compliance is engineered. Outrage is rewarded; nuance is punished; truth is slowed by friction while lies are accelerated by design. “Live in truth” looks like building systems that don’t monetize manipulation. It means transparency about how information is amplified. It means refusing “engagement” as the highest good. The action for a citizen is also practical: don’t share what you can’t verify, don’t let fear drive your attention, don’t outsource your agency to a feed.

Francis Fukuyama: “Live in truth” is also institutional, not only personal. Democracies collapse not only when people lie, but when they stop believing that truth is possible—or that it matters. So the action is rebuilding competence: governments that can deliver, courts that can enforce, regulators that can investigate. If institutions are weak, ritual compliance becomes the substitute—people perform morality because they cannot achieve it. Living in truth requires functioning systems that make truth consequential again.

Zanny nods, then shifts the angle—because the next question is where morality meets geopolitics.

Zanny Minton Beddoes: Here’s the harder layer. In an age of weaponized interdependence—trade, finance, energy—some leaders claim “we must perform the rituals” to keep systems stable, even if the rituals are hollow. Is there a point where ritual compliance becomes not stability, but surrender? And how do you tell the difference?

Anne Applebaum: The difference is whether the ritual hides coercion. When institutions pretend a captured judiciary is “rule of law,” when companies treat censorship as “local compliance,” when governments call repression “sovereignty,” the ritual becomes surrender. The test is this: does the ritual protect vulnerable people, or does it protect the powerful from accountability? If it’s the latter, it’s not stability—it’s complicity.

Mark Carney: I’d frame it as resilience versus fragility. Ritual compliance creates fragility because it masks risk. If you don’t admit your dependency on a single energy route or a single supplier, you cannot build redundancy. If you pretend inflation is transitory when it isn’t, you lose credibility. Stability isn’t achieved by comforting theater; it’s achieved by real buffers—diversified supply chains, credible fiscal frameworks, enforceable commitments. The line is crossed when the ritual prevents preparation.

Francis Fukuyama: There’s also a legitimacy threshold. If citizens perceive rituals as lies, they stop trusting the entire system, including the parts that work. Then populists exploit the vacuum. So ritual compliance may “hold things together” briefly, but it corrodes legitimacy over time. The difference is whether the ritual is backed by enforceable reality. If it’s merely symbolic, it becomes a corrosive tax on trust.

Václav Havel: Rituals can be humane when they are bridges—when they give people a language to cooperate before they fully agree. But when rituals are used to deny reality, they become chains. The greengrocer is told, “Hang the slogan for peace.” But the slogan is not peace; it is obedience. How do you tell? Listen for fear. When a ritual is sustained primarily by fear—fear of losing status, fear of punishment, fear of being excluded—then it is not a bridge. It is a leash.

Maria Ressa: Today the rituals are also performed for surveillance—by states and by platforms. “Safety” becomes a ritual word; “misinformation” becomes a ritual weapon; “community standards” can become a ritual cover for censorship or favoritism. The difference is transparency and due process. If a system cannot show you how decisions are made, it’s not stability—it’s control.

Zanny lets the room breathe. Snow taps softly at the glass like punctuation.

Zanny Minton Beddoes: Final question. If “live in truth” is the antidote to ritual compliance, what is the minimum viable courage required—at the level of leaders, institutions, and citizens—so that truth becomes socially survivable again? What’s the smallest act that can start a cascade?

Mark Carney: Leaders must stop promising what they cannot fund or enforce. The minimum viable courage is to put numbers to commitments—and accept consequences for missing them. For institutions, it’s radical transparency: publish assumptions, publish risks, publish tradeoffs. For citizens, it’s supporting leaders who speak honestly even when it hurts. Truth becomes survivable when honesty is rewarded, not punished.

Maria Ressa: The smallest act is to refuse to be manipulated. Pause before you share. Demand receipts. Support independent journalism. Build community spaces where disagreement doesn’t mean dehumanization. Truth becomes survivable when people reclaim agency over attention—because attention is the currency of control.

Václav Havel: The smallest act is to stop lying in one place where you have been lying to survive. Say the honest sentence in the meeting. Remove the slogan from the window. Not as a performance—quietly. This is how regimes of falsity crack: not from one grand revolution, but from millions of small withdrawals of consent.

Anne Applebaum: Institutions must protect truth-tellers. The minimum viable courage is creating consequences for corruption and propaganda—real investigations, real prosecutions, real sanctions. And for elites—political, corporate, cultural—the minimum viable courage is to stop pretending neutrality when the issue is democracy versus coercion. Silence becomes a ritual too.

Francis Fukuyama: Rebuild competence. It sounds unromantic, but it’s essential. When states deliver—when courts function, when basic services work—citizens feel less tempted by myth. Truth becomes survivable when reality feels livable. The smallest act might be bureaucratic: an inspector doing their job, a judge resisting pressure, a civil servant refusing to falsify data. That’s where legitimacy is born.

Zanny closes her notebook. No crescendo, no applause—just the quiet recognition that this topic is not about Eastern Europe in the 1970s or 1980s. It’s about the present.

Because “live in truth” isn’t a slogan to hang in the window.

It’s the moment you decide you won’t hang slogans anymore—and you accept whatever comes next.

Final Thoughts by Mark Carney

If there is one mistake we cannot afford, it is the temptation to wait for yesterday’s normal to return. Waiting is not neutral. In a rupture, waiting is a decision—one that hands initiative to those most willing to exploit uncertainty.

The good news is that middle powers are not helpless. But influence today doesn’t come from speeches. It comes from structures: resilient energy systems, diversified supply chains, trusted financial plumbing, and coalitions that make coercion expensive. It comes from standards that are applied consistently, not selectively. And it comes from investing in institutions that can act—quickly, credibly, and fairly—when shocks arrive.

We should be realistic about costs. Resilience requires investment, coordination, and sometimes restraint. But the cost of vulnerability is higher, because it is paid at moments of maximum stress—when choices narrow and fear crowds out judgment.

So I’ll end where I began: name reality plainly, then build. Reduce the choke points. Strengthen your domestic foundations. Cooperate with partners who are willing to share burdens and benefits. And resist the false comfort of fortress economics. Our aim should be a world that is safer because it is less coercible—and more prosperous because it remains open where openness still works.

That is what it means to be principled and pragmatic in a time of rupture.

Short Bios:

Mark Carney — Canadian prime minister and former central banker known for steering institutions through crisis, blending market realism with “values-based” strategic planning.

Fareed Zakaria — Global affairs commentator and host known for crisp, big-picture moderation that turns complex geopolitics into clear, testable ideas.

Christine Lagarde — President of the European Central Bank, a leading voice on inflation, stability, and Europe’s push for resilience without panic or isolation.

G. John Ikenberry — Princeton scholar of international order who studies how rules, legitimacy, and alliances survive—or fail—when power shifts.

Graham Allison — Harvard strategist behind “Thucydides Trap” thinking, focused on great-power rivalry, miscalculation risk, and guardrails that prevent catastrophe.

Niall Ferguson — Historian and essayist who tracks the rise and decline of empires, financial power, and the hidden costs of “order.”

Gillian Tett — Financial Times editor and anthropologist who spots structural shifts early, translating market plumbing into human incentives and power dynamics.

Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala — Director-General of the WTO, championing trade rules and development fairness while navigating the new era of security-driven economics.

Robert Lighthizer — Trade lawyer and former U.S. trade negotiator associated with tariff-first strategy and the view that trade is inseparable from national power.

Eswar Prasad — Economist specializing in global finance, currencies, and payment systems, explaining how the “plumbing” of money becomes geopolitical leverage.

Adam Tooze — Economic historian known for sharp, systems-level analysis of crises, state power, and how global economic architecture can be weaponized.

Martin Wolf — Influential Financial Times columnist who interrogates policy tradeoffs with disciplined economics, especially the costs and limits of “strategic autonomy.”

Dani Rodrik — Economist of globalization’s limits, arguing for democratic policy space and “smart” interdependence instead of blanket self-sufficiency.

Larry Summers — Economist and former U.S. Treasury secretary, skeptical of broad industrial-policy sprawl, emphasizing disciplined tradeoffs and cost-aware resilience.

Mariana Mazzucato — Economist advocating “mission-driven” public investment and innovation policy, pushing for governance that creates public value—not just private gains.

Fatih Birol — Executive Director of the International Energy Agency, focused on energy security, transition realities, and the infrastructure needed for resilience.

Ian Bremmer — Political risk analyst who frames global politics as incentives and power, pressing panels to translate slogans into executable strategy.

Anne-Marie Slaughter — International relations thinker known for “network power,” emphasizing coalitions built through interoperable standards and institutional connectivity.

Stephen Walt — Realist scholar of alliances and threat perception, blunt about how coalitions actually hold: shared interests, credible commitments, and burden-sharing.

Kishore Mahbubani — Singaporean strategist urging pragmatic multipolar thinking, warning against moralized blocs and pushing flexible, interest-based cooperation.

Dambisa Moyo — Economist and author focused on development, capital flows, and resource strategy, arguing coalitions must deliver real investment and value-add to producers.

Leave a Reply