|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

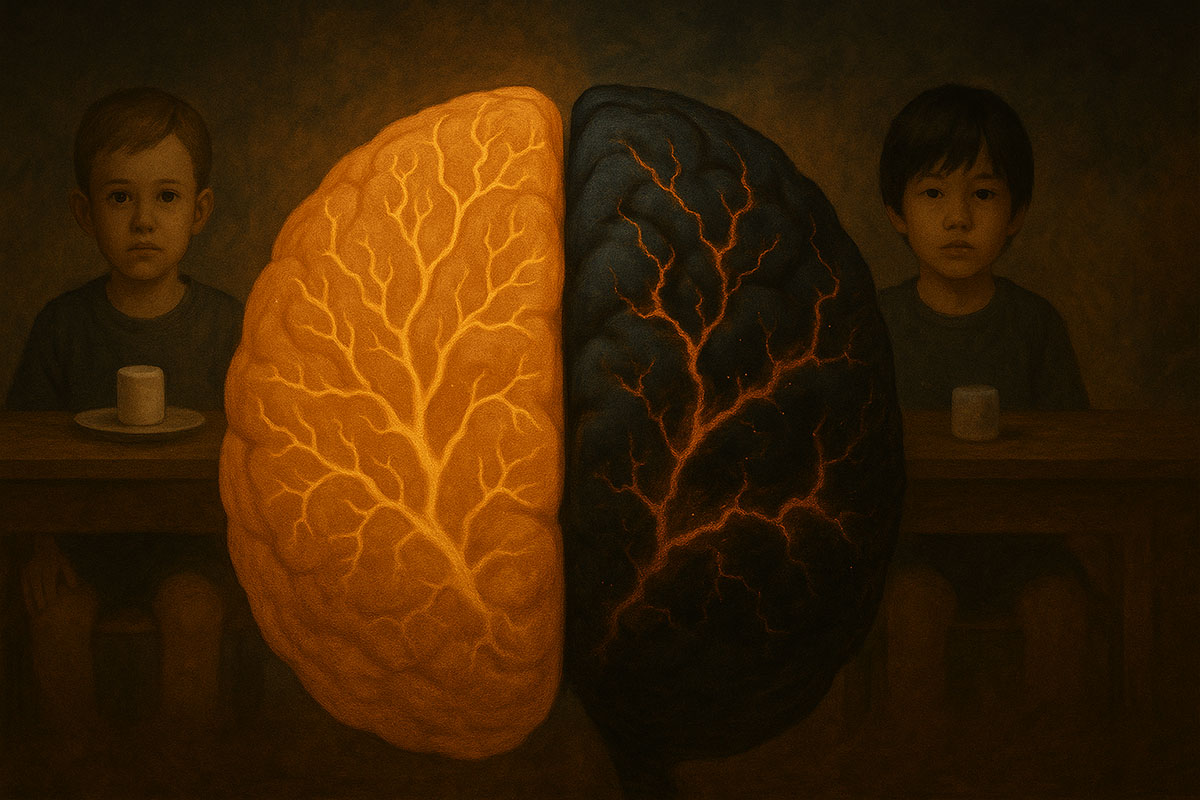

Introduction by Malcolm Gladwell

When you place a marshmallow in front of a child, you aren’t simply testing their willpower. You’re holding up a mirror to the most profound human dilemma: do we live for today, or for tomorrow? For decades, the marshmallow experiment has been treated as a parable of patience, a neat story about children who wait and later succeed. But in truth, the marshmallow tells us much more. It speaks of trust, of scarcity, of the way society shapes our choices. It whispers about wealth and inequality, about technology and temptation, about what it means to live in a world of constant reward and endless opportunity.

The marshmallow is not just a sweet. It is a test of faith in the future. And that is why, in this series, we will follow the marshmallow across psychology, economics, and culture, asking the deeper question: what does it mean to wait—and what does it mean to act?

(Note: This is an imaginary conversation, a creative exploration of an idea, and not a real speech or event)

Topic 1: The Science of Self-Control: Nature, Nurture, or Both?

Daniel Kahneman (opening)

We are here to explore the roots of self-control. The marshmallow experiment gave us a striking metaphor for human patience, but the truth is more nuanced. I want to begin with this: Is self-control something innate in children, or is it primarily shaped by environment and teaching?

Walter Mischel

When I first conducted the marshmallow experiment, I believed we were glimpsing an internal trait, a stable capacity for delay. But later, I realized the environment mattered greatly. A child who grows up in reliable conditions may feel safe to wait; in an uncertain world, seizing the marshmallow now is perfectly rational. It is less about innate strength and more about the interplay of trust and opportunity.

Angela Duckworth

From my perspective, self-control is like a muscle—it can be strengthened through practice. While some children show early temperamental differences, what determines their trajectory is often the cultivation of habits. Teaching kids to structure their environment, to avoid temptation, or to build routines can transform their capacity for self-control.

Carol Dweck

I see self-control as deeply tied to mindset. If a child believes their abilities and outcomes are fixed, waiting feels pointless. But if they have a growth mindset—that their patience and effort can change the future—they’re more willing to wait. Environment may provide cues, but belief systems transform those cues into action.

Robert Sapolsky

As a neuroscientist, I would add biology into this mix. Some kids’ prefrontal cortexes simply develop faster, giving them more impulse regulation. Others may have stress hormones constantly surging, making delay unbearable. Genes, brain development, and hormones all sculpt self-control. But biology is never destiny—it’s biology plus environment, in constant dialogue.

Daniel Kahneman

You’ve all touched on something important: the complexity of cause. Let me push further. If we think of self-control as both biology and training, what are the best interventions? Should schools, families, or societies bear the responsibility for nurturing delayed gratification?

Angela Duckworth

Schools have a major role. Teaching self-regulation strategies—like setting goals, monitoring progress, or using small rewards—creates a culture of discipline. Programs that teach grit and self-control can help level the playing field, especially for children from unpredictable backgrounds.

Robert Sapolsky

But let’s be careful. If you put a child under chronic stress—poverty, instability, violence—you cannot simply teach them breathing exercises and expect miracles. Societal structures matter. Reduce inequality and insecurity, and suddenly kids have the bandwidth to think about tomorrow.

Carol Dweck

I’d add that parents and teachers must communicate faith in a child’s ability to grow. Encouragement and modeling patience are interventions too. A mindset of hope—"waiting will make things better"—must be believable.

Walter Mischel

Exactly. That’s why in later variations of the experiment, when we manipulated trust—by showing children that adults kept or broke promises—their waiting times shifted dramatically. Interventions must build both skill and trust in the promise of reward.

Daniel Kahneman

So environment and trust are as critical as discipline and biology. Let’s close with one last dimension. Many assume delayed gratification is always the wiser choice. But is there a danger in glorifying waiting too much? Could immediate action sometimes be the better strategy?

Robert Sapolsky

Evolutionarily, yes. Our ancestors survived by grabbing food when it was available. Delaying could mean starvation. Impulsivity isn’t just weakness—it’s an adaptation for uncertain environments.

Walter Mischel

Indeed. My experiment was never meant to glorify waiting for waiting’s sake. It was about context. In a stable world, patience pays off. In an unstable one, seizing the marshmallow can be smart.

Carol Dweck

I agree. The danger is in moralizing patience. True wisdom is in flexibility: knowing when to wait and when to act.

Angela Duckworth

And in teaching people how to design their lives accordingly. Sometimes the path to success is about discipline. Other times, it’s about seizing fleeting opportunities.

Daniel Kahneman (closing)

So perhaps the lesson is this: self-control is neither purely innate nor purely learned. It is a dialogue between biology, mindset, trust, and circumstance. And wisdom lies not in always waiting, but in recognizing when waiting leads to flourishing.

Topic 2: Trust, Scarcity, and the Psychology of Waiting

Esther Duflo (opening)

The marshmallow experiment revealed that trust in the future shapes whether a child waits or not. But I want to begin by asking: How much does scarcity, poverty, and lived experience affect our willingness to delay gratification compared to individual willpower?

Sendhil Mullainathan

Scarcity captures the mind. When resources are scarce, attention narrows. It’s not that poor people lack willpower; it’s that the urgent need of the present consumes cognitive bandwidth. Waiting for the second marshmallow is hard when you’re worried about tonight’s dinner.

Eldar Shafir

Exactly. Scarcity changes the psychology of time. In environments where tomorrow feels uncertain, taking the sure thing now is rational. Self-control is not just about individual capacity—it’s about the perceived reliability of the future.

Dan Ariely

I’d add that people in scarcity are also exposed to broken promises more often. If the system doesn’t deliver, waiting feels foolish. We mustn’t moralize impatience when the environment teaches people not to trust.

Rutger Bregman

That’s why the real solution is not teaching more willpower but creating systems of trust and security. When people know the future will come, and that society won’t abandon them, patience emerges naturally. A universal basic income, for example, could change the entire psychology of waiting.

Esther Duflo

That brings me to the next question. If trust and reliability matter so much, what can societies do to create environments where people feel safe enough to delay gratification?

Eldar Shafir

Policy must reduce unpredictability. Reliable welfare programs, consistent rules, and systems that actually deliver help are crucial. If people trust the institutions, they can think long-term.

Rutger Bregman

Yes, social safety nets are trust machines. A basic income, guaranteed healthcare, or secure housing create psychological space for people to plan ahead instead of grabbing whatever is in front of them.

Dan Ariely

On a smaller scale, companies and schools can model reliability too. If teachers or employers consistently follow through on promises, they train people to expect the future to pay off.

Sendhil Mullainathan

I’d caution, though, that trust is fragile. One broken promise can undo months of progress. Policy design must ensure not just generosity, but reliability. People need to experience the system as dependable.

Esther Duflo

That’s a powerful reminder. Let me close with one final question: Is there ever wisdom in taking the marshmallow now? When does impatience become the rational, even the optimal, choice?

Dan Ariely

Absolutely. If you’re in a volatile environment, grabbing the immediate reward may maximize survival. Think of refugees or those in failing economies—it can be foolish to wait for a promise that may never come.

Eldar Shafir

Yes. Rationality is contextual. We must shift our language: impatience is not weakness, it’s adaptation. The marshmallow test without context risks becoming a moral judgment instead of a behavioral insight.

Rutger Bregman

But we must also dream bigger. If society creates stable futures, fewer people will face that choice. Impatience becomes rational only because we have built irrational systems.

Sendhil Mullainathan

The real challenge, then, is to ensure that taking the marshmallow now is never the only rational option. That requires stability, trust, and fairness in our systems.

Esther Duflo (closing)

So perhaps the lesson is this: scarcity and mistrust do not merely limit willpower, they reshape what it means to be rational. If we want people to wait for tomorrow, we must give them a tomorrow worth waiting for.

Topic 3: Delayed Gratification in the Digital Age

Tristan Harris (opening)

The world today is built around instant gratification: likes, notifications, one-click purchases. I want to begin with this: Has technology fundamentally rewired our brains to expect immediacy, making delayed gratification harder than ever before?

Nicholas Carr

I would say yes. The internet, and especially smartphones, shorten our attention spans. We skim instead of reading deeply, scroll instead of contemplating. Our neural pathways adapt to constant novelty, so waiting—whether for knowledge or reward—feels unnatural.

Cal Newport

And yet, technology doesn’t erase our ability to delay. It simply raises the cost. Deep work still requires sustained focus, but now we must actively fight back against an environment engineered for distraction. Our brains aren’t broken; they’re responding predictably to incentives.

Sherry Turkle

But it’s not only about the brain. It’s also about relationships. When a child texts and receives an immediate response, they learn that patience in communication is unnecessary. Technology changes not just cognition but social expectation.

Jean Twenge

We see this especially in Gen Z. They’ve grown up in a culture where instant gratification is the norm. Rates of anxiety and depression rise in part because waiting—whether for success, relationships, or self-worth—is almost intolerable. They’ve been conditioned to live in the “now.”

Tristan Harris

That leads us to the next question. If tech companies profit from designing for immediacy, what can individuals and societies do to protect the capacity for patience and long-term thinking?

Cal Newport

Individuals must reclaim control by creating boundaries. Turn off notifications, set time for deep work, and train the mind to tolerate boredom. These small acts rewire attention away from the quick fix.

Jean Twenge

Parents and schools play a vital role. Children need protected spaces without screens—time outdoors, face-to-face conversations, unstructured play. That’s how they learn to wait, to imagine, to delay gratification.

Sherry Turkle

I’d add that society must rethink its relationship to tech. Regulation may be necessary. If platforms profit by exploiting impatience, then the responsibility isn’t just on individuals to resist—it’s on us collectively to demand humane design.

Nicholas Carr

And culturally, we must value slowness again. Books, music, long conversations—these are antidotes to instant consumption. The arts remind us that some rewards can’t be rushed.

Tristan Harris

Important points. Let me ask one final question: Is there a danger in glorifying patience too much? In a fast-paced digital world, could waiting actually mean missing out?

Sherry Turkle

Yes, sometimes immediacy fosters connection. A quick response to a friend in crisis can save a relationship. Not all instant gratification is shallow; some is profoundly human.

Nicholas Carr

But we must distinguish urgency from compulsion. True urgency—responding to a crisis—is different from the compulsive need to refresh a feed. Most of what feels urgent is manufactured by algorithms.

Jean Twenge

I agree. For young people, the key is balance. Teach them that sometimes it’s wise to act now, but also to recognize when waiting creates deeper satisfaction.

Cal Newport

And from a productivity standpoint, immediacy often leads to shallow decisions. Waiting—even briefly—improves judgment. The danger is not waiting too long, but mistaking constant motion for progress.

Tristan Harris (closing)

So the lesson is clear: technology amplifies our craving for immediacy, but the capacity to wait remains within us. The challenge is to design lives and societies where patience is not a relic of the past but a foundation for the future.

Topic 4: From Marshmallows to Millions: Financial Patience and Wealth Building

Warren Buffett (opening)

We’ve seen how waiting for a second marshmallow can translate into waiting for compounded returns in finance. Let me begin with this: Why do so many people struggle with financial patience, even when the math of saving and compounding is so clear?

Suze Orman

Because emotions often override math. People buy cars they can’t afford, swipe credit cards for short-term joy, and delay saving because the future feels abstract. Financial literacy helps, but at its heart, impatience with money is often emotional, not logical.

Ray Dalio

I’d add that the system itself encourages short-termism. Quarterly earnings, political cycles, media noise—all push people toward immediacy. The culture of capitalism often rewards the quick hit rather than the long build.

Thomas Piketty

And let’s not forget inequality. Many people can’t afford to wait because they’re trapped by low wages, high rents, and debt. Delayed gratification is easier when your basic needs are met. For the poor, grabbing the marshmallow may be survival, not weakness.

Morgan Housel

Yes, and even among the well-off, human psychology is wired for immediacy. The brain values today more than tomorrow. That’s why patience in investing is so rare—and why it’s so rewarded. Those who can endure boredom often outperform those chasing excitement.

Warren Buffett

Interesting. Let’s go deeper. If patience is so critical to wealth, how can individuals and societies cultivate financial habits that encourage waiting for tomorrow rather than spending it all today?

Suze Orman

Automation is one solution. If savings are automatic—retirement contributions, investment transfers—people don’t have to fight temptation each month. Structure beats willpower.

Morgan Housel

Storytelling matters too. If we frame saving as giving your “future self” a gift, people connect emotionally. Patience becomes less about deprivation and more about generosity to your future.

Ray Dalio

From a systems view, we must encourage policies that reward long-term behavior: tax incentives for retirement saving, capital gains breaks for long-term holdings, and education that starts early. Society can nudge patience through design.

Thomas Piketty

But structural inequality must also be addressed. Patience is a privilege if the poor cannot afford to save. Progressive taxation, wealth redistribution, and affordable housing make delayed gratification possible for everyone, not just the rich.

Warren Buffett

Good. Now let’s finish with one more question. Is patience always the best financial strategy? Or are there times when seizing the first marshmallow—the quick gain—is the wiser move?

Ray Dalio

Timing matters. In crises, holding cash instead of waiting for theoretical future gains can mean survival. Patience must be balanced with adaptability to changing environments.

Suze Orman

Yes. If you’re drowning in high-interest debt, the smartest move is not to wait—it’s to pay it off immediately. Sometimes action beats compounding.

Thomas Piketty

And politically, patience is not always rewarded. Workers waiting for trickle-down promises may wait forever. Sometimes collective impatience is needed to demand fairness now.

Morgan Housel

I’d argue that even quick action can be reframed as long-term patience. Paying off debt, building an emergency fund, or grabbing an opportunity can actually extend your ability to be patient later.

Warren Buffett (closing)

So the lesson is not that patience is always right, but that wisdom lies in knowing when to wait and when to act. Wealth is built not just on compounding returns, but on compounding good decisions—timely patience mixed with timely boldness.

Topic 5: Redefining Success: Should Waiting Always Be Rewarded?

Malcolm Gladwell (opening)

We’ve been talking about the virtues of patience, but I want to begin by questioning the premise. Is waiting always a virtue? Or can delayed gratification blind us to opportunities that only exist in the present moment?

Nassim Nicholas Taleb

Waiting can be dangerous if it assumes the future will look like the past. Black Swan events—the rare, unexpected—reward those who act decisively. Many fortunes are made not by waiting patiently, but by seizing asymmetric opportunities.

Elizabeth Gilbert

As a writer, I’d say the same. Creativity doesn’t always reward patience. Sometimes the spark comes and you must leap. Waiting for the “perfect” time can mean losing the chance altogether.

Alain de Botton

But patience has its place in philosophy. We often rush through life seeking quick thrills and miss deeper meaning. While waiting is not always rewarded materially, it can be spiritually enriching, teaching acceptance and perspective.

Adam Grant

In organizations, both are true. Some careers thrive on patient apprenticeship, while others demand risk-taking. The challenge is discernment—knowing when patience builds resilience and when it calcifies into stagnation.

Malcolm Gladwell

That brings me to the next question. If patience isn’t universally good, how should we teach the next generation to balance waiting with boldness?

Elizabeth Gilbert

We should teach them to listen to their own intuition. Patience is valuable, but if waiting feels like fear disguised as wisdom, that’s when you need to act.

Adam Grant

I’d emphasize experimentation. Young people should try things quickly, fail, and learn. Patience should apply to long-term growth, but not to staying stuck in something unfulfilling.

Alain de Botton

Philosophically, I’d say we should also teach them that waiting is not passive. It is active reflection, gestation. Sometimes the most radical act is to pause, to allow time to ripen insight.

Nassim Nicholas Taleb

I disagree partly. We must avoid teaching patience as submission. Teach optionality: keep yourself in a position to seize upside without catastrophic risk. That means small bets, trial and error, not blind waiting.

Malcolm Gladwell

Fascinating. Let me ask one final question. How should we redefine success itself—so that waiting, seizing, patience, and boldness are all seen not as opposites, but as parts of the same journey?

Alain de Botton

Success should be judged less by outcomes and more by the quality of life experienced along the way. Patience and boldness both contribute to meaning, not just money.

Elizabeth Gilbert

Yes. Success is living a creative life where you act when inspiration strikes, and wait when the soul demands rest. Both patience and immediacy are tools for alignment with purpose.

Adam Grant

In the workplace, success could be redefined as adaptability—valuing those who can shift between patience and speed depending on the context. That flexibility is the modern virtue.

Nassim Nicholas Taleb

For me, success is survival with dignity. Waiting is sometimes wise, sometimes fatal. Seizing is sometimes brave, sometimes foolish. Success is having the robustness and antifragility to thrive no matter what life throws at you.

Malcolm Gladwell (closing)

So we end where we began—with a paradox. Patience is not a universal key, nor is immediacy. True success lies in knowing when to wait, when to leap, and in embracing both as part of a life fully lived.

Final Thoughts by Malcolm Gladwell

If the marshmallow effect began as a study of children, it ends as a study of us all. The choices we make—between now and later, between trust and fear, between patience and urgency—shape the arc of our lives. We can no longer pretend the marshmallow is only about willpower. It is about context. It is about inequality. It is about the design of our world.

Sometimes, the wise thing is to wait. Other times, the wise thing is to leap. Success is not built on patience alone, nor on boldness alone, but on the delicate art of knowing when to do each. The marshmallow was never the answer. It was always the question. And it is a question we are still learning how to answer—together.

Short Bios:

Walter Mischel — Psychologist who created the famous Stanford Marshmallow Experiment, his work revealed how delayed gratification links to later success.

Angela Duckworth — Psychologist and author of Grit, she studies perseverance, self-control, and how habits shape achievement.

Carol Dweck — Stanford psychologist known for her growth mindset theory, showing how belief in improvement drives resilience.

Robert Sapolsky — Neuroscientist and author, he researches stress, biology, and behavior, blending science with storytelling.

Daniel Kahneman — Nobel Prize–winning psychologist and author of Thinking, Fast and Slow, pioneer of behavioral economics.

Eldar Shafir — Cognitive scientist whose research explores scarcity, decision-making, and the psychology of poverty.

Sendhil Mullainathan — Economist and co-author of Scarcity, he studies how limited resources shape thought and choices.

Dan Ariely — Behavioral economist and author of Predictably Irrational, he explores human quirks in decision-making.

Rutger Bregman — Dutch historian and author of Utopia for Realists, he advocates for universal basic income and social trust.

Esther Duflo — Nobel Prize–winning economist, co-founder of J-PAL, her research focuses on poverty alleviation and development.

Cal Newport — Author of Deep Work and Digital Minimalism, he studies focus, productivity, and the cost of distraction.

Sherry Turkle — MIT professor and author of Alone Together, she explores technology’s impact on relationships and identity.

Nicholas Carr — Technology writer and author of The Shallows, he examines how the internet reshapes our thinking.

Jean Twenge — Psychologist studying generational trends, especially the effects of smartphones on Gen Z mental health.

Tristan Harris — Former Google ethicist, co-founder of the Center for Humane Technology, advocate for ethical tech design.

Warren Buffett — Legendary investor, chairman of Berkshire Hathaway, known for patience, long-term thinking, and compounding wealth.

Ray Dalio — Hedge fund manager and founder of Bridgewater Associates, author of Principles, expert on economic cycles.

Suze Orman — Financial advisor and bestselling author, she teaches personal finance, savings, and debt reduction.

Thomas Piketty — French economist and author of Capital in the Twenty-First Century, known for his work on inequality.

Morgan Housel — Financial writer and author of The Psychology of Money, he explores behavior and money management.

Malcolm Gladwell — Author of Outliers and The Tipping Point, he weaves research and storytelling to challenge assumptions.

Alain de Botton — Philosopher and founder of The School of Life, he writes on love, work, and the pursuit of happiness.

Nassim Nicholas Taleb — Statistician and author of The Black Swan and Antifragile, he critiques risk, randomness, and fragile systems.

Elizabeth Gilbert — Author of Eat, Pray, Love and Big Magic, she explores creativity, risk, and living authentically.

Adam Grant — Wharton professor and author of Think Again and Give and Take, he studies motivation, generosity, and innovation.

Leave a Reply