|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

What if the Trump Davos 2026 speech was debated by the world’s toughest realists—then rebuilt into a practical playbook?

Introduction by Donald J. Trump

In my Davos speech, I said the thing a lot of people were thinking, but wouldn’t say out loud:the world runs on strength, fairness, and results—not on endless meetings and pretty statements. Davos is full of smart people, very smart, but for years we watched the same problems get worse because leaders were afraid to enforce anything.

So I came in with a simple idea: if the deals are bad, we fix the deals. If the borders are weak, we secure the borders. If the burden is unfair, we make it fair. That’s not “controversial”—that’s leadership. And yes, it changed the agenda, because it touched the pressure points everyone cares about: security, trade terms, energy, and stability.

We’re going to look at these issues without the usual fog. Tariffs are leverage. Leverage creates deals. Deals create predictability—when they’re enforced. The Arctic is strategic, and I said clearly I’m not talking about force—I'm talking about smart arrangements that keep America and our allies safe. And the “Board of Peace” idea is about one thing: stopping the theater and getting outcomes. People can criticize the tone. I’m focused on the scoreboard.

(Note: This is an imaginary conversation, a creative exploration of an idea, and not a real speech or event.)

Topic 1: The Gravitational Field — How One Speech Rewrites Everyone’s Agenda

Snow presses against the glass like a silent audience. In a private Davos side room—half boardroom, half bunker—a round table sits under warm lights that can’t quite thaw the mood. Outside, the Annual Meeting continues like a well-oiled machine. Inside, the machine is being reprogrammed.

David Ignatius: This is an imaginary roundtable, but the effect we’re describing was real enough: one speech that bent the whole week around it. I want to start with the simplest, sharpest question—because it’s also the most uncomfortable. How does one person’s speech become the gravitational field for everyone else’s agenda? Is it policy, tone, threat, charisma… or the fact that people can’t afford to ignore it?

Ian Bremmer: It’s power plus uncertainty. Not just what you say—what you might do. When you’re the actor who can reset trade terms, alliance expectations, energy posture, and the diplomatic temperature with a sentence, everyone recalculates. The gravitational field isn’t the speech. It’s the reaction function it triggers.

Anne Applebaum: And it’s also spectacle. Modern politics is attention as coercion. If you can make every room talk about you, you can force moral choices and strategic choices—who condemns, who flatters, who stays silent. That’s why the tone matters so much; it’s not decoration. It’s part of the mechanism.

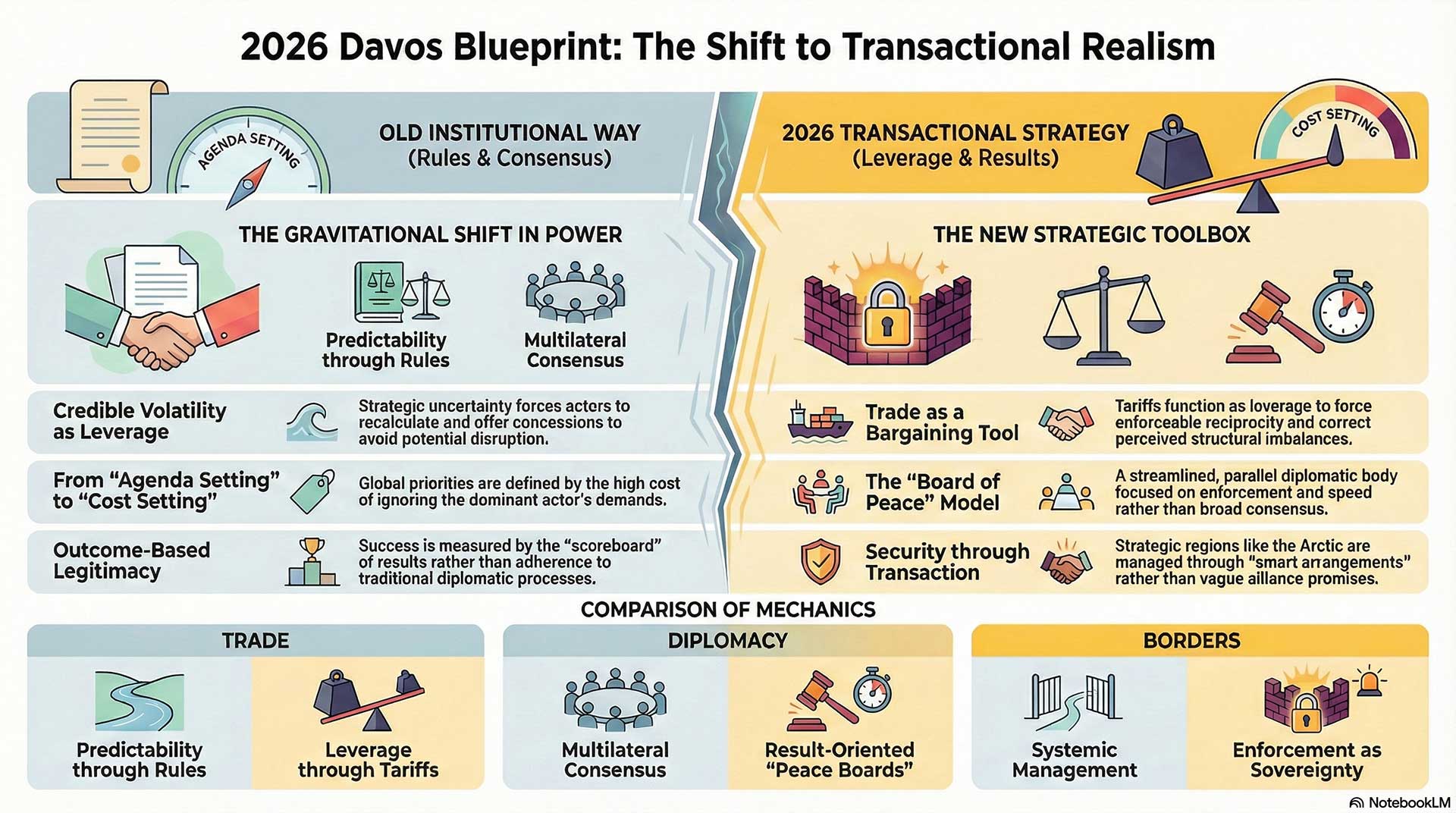

Stephen Walt: Let’s strip the romance away. It’s material power. The U.S. has enormous leverage. When the leader signals he’s willing to use it more bluntly, other states must respond. The speech becomes gravity because ignoring it is costly. People talk about “agenda setting,” but it’s really “cost setting.”

Mark Rutte: And from an ally’s point of view, it’s also bandwidth. You can’t do twenty strategic projects when you’re trying to interpret one actor’s next move. So yes—everyone orbits. Not because they want to, but because the consequences hit first.

Donald J. Trump: Look—everyone’s always been watching America. I just say it clearly. If something is unfair, we’re not going to pretend it’s fair. If we’re paying and others aren’t, that changes. People call it “gravity.” I call it reality. You can either deal with reality or you can do speeches to each other.

David Ignatius: Interesting—so for some of you, it’s “uncertainty as force,” for others it’s “attention as force,” and for others it’s simply “capability.” Let me press this into the second layer. When allies and rivals react to tone as much as substance, what becomes the real currency of diplomacy? Is it credibility? Is it theater? Is it intimidation? Is it deal-making?

Anne Applebaum: In an anxious era, “tone” signals norms. A calm, institutional tone implies restraint and continuity. A combative tone implies rupture and dominance. People respond because they’re trying to locate the new boundary of acceptable behavior. That’s why it’s dangerous—once you normalize humiliation, you don’t just change policy; you change what politics feels like.

Donald J. Trump: Tone? That’s just what people say when they don’t want to talk about results. Diplomacy is leverage. You want peace? You have leverage. You want good trade? You have leverage. You want borders that mean something? You enforce them. People can call it theater. I call it getting it done.

Ian Bremmer: Tone is policy in a world where signals move markets and alliances. “I might do something dramatic” forces preemptive concessions. “I’m predictable” forces slower negotiation. The currency becomes credible volatility—the ability to create uncertainty while still being believed. That’s rare, and it’s powerful, and it’s also risky if overused.

Mark Rutte: For allies, the currency becomes reassurance plus clarity. We can handle tough negotiation. What we struggle with is ambiguity that leaks into security commitments. Tone can amplify ambiguity—either calming it or inflaming it. If the tone makes everything sound transactional, allies start building hedges. That becomes self-fulfilling.

Stephen Walt: The currency is credibility, not charm. But credibility can be established by being consistent—or by being feared. Both work. The difference is the long-run cost. Fear-based credibility can yield quick gains and long-term resistance. Consistency-based credibility is slower and often less thrilling, but it builds durable cooperation.

David Ignatius: So we’ve got a spectrum: norms and legitimacy on one side, leverage and results on the other, and in the middle this idea of “credible volatility.” Now I want the third question to be the one everyone avoids because it forces you to pick a theory of history. Does this style reduce the risk of war by forcing clarity and deterrence—or raise the risk by turning everything into a public test of dominance?

Stephen Walt: Both possibilities exist, but the mechanism matters. If the style clarifies red lines and reduces misreading, it can lower risk. If it creates constant status contests—where backing down is humiliation—then it raises risk. Great-power crises are often status crises in disguise. The more public the contest, the harder it is to de-escalate.

Ian Bremmer: The danger is escalation through performative commitment. When leaders speak to the world as if they’re speaking to a crowd, they lock themselves in. But the upside is that ambiguity can also be destabilizing—people miscalculate. So the question is whether the “clarity” is accompanied by off-ramps. Tough talk without off-ramps is a trap.

Donald J. Trump: I’ll tell you what reduces war—strength. When people know you’re serious, they don’t test you. The problem with the old way is everybody was testing. Testing on trade, testing on borders, testing on energy. If you stop the testing, you stop the problems. That’s peace through strength. It’s not complicated.

Anne Applebaum: Strength is not the same as theatrical dominance. War risk rises when institutions are weakened and decisions become personal. If everything depends on one leader’s mood or one leader’s need to “win,” then adversaries start gambling on psychology instead of policy. And allies start doubting reliability. That combination—adversaries gambling, allies hedging—is exactly how you drift into dangerous miscalculation.

Mark Rutte: I’ve watched deterrence work, and I’ve watched miscommunication nearly break things. Strength matters. But alliances are also about trust—trust that commitments are steady, that the rules don’t change mid-crisis. If the style turns every issue into a deal on the spot, then in a crisis people won’t know the floor beneath their feet. That uncertainty can invite exactly the kind of test President Trump says he wants to prevent.

David Ignatius: Let me reflect what I’m hearing. President Trump is arguing that clarity plus strength reduces testing. Anne is warning that personalization and public dominance games can increase testing. Ian is saying the key is off-ramps. Stephen is saying status contests are the hidden accelerant. Mark is saying alliances need predictability to deter.

He leans forward, voice softening a notch—because the room is hot enough already.

David Ignatius: Here’s what I want to pin down before we move to the next topic in this series. If the “gravitational field” is real, then the question isn’t whether people orbit. They will. The question is what kind of orbit it creates: stable, predictable, and deterrent—or erratic, brittle, and crisis-prone.

Donald J. Trump: Stable comes from fairness. People don’t like hearing it, but it’s true. When the deals are fair, you get stability. When they’re not, you get weakness and resentment. I’m fixing the fairness.

Anne Applebaum: Stability also comes from legitimacy. If the system looks like raw power, it eventually produces coalitions against raw power.

Stephen Walt: Stability comes from incentives that make restraint rational. You can do that through institutions, or through deterrence, or through a balance of power. But you need something that doesn’t depend on personality.

Ian Bremmer: And you need a world where you can be tough without making every outcome a public humiliation. That’s the single biggest design problem right now.

Mark Rutte: Which is why allies will keep adapting—quietly. Even when the spotlight is loud.

The snow outside keeps falling. Inside, nobody reaches for closure—because the next topics (trade, security, “peace boards,” borders) are already waiting in the hallway, tapping their foot.

Topic 2: Trade as Leverage — Tariffs, Deals, and the Return of Hard Bargaining

The Davos air feels different in this room—less champagne, more spreadsheets. A long table. Five microphones that nobody needs. The kind of quiet that happens when everyone knows the numbers, but nobody agrees on what the numbers mean.

Gillian Tett taps a pen once, like a metronome for the week’s central obsession.

Gillian Tett: Let’s treat this like a stress test, not a slogan contest. President Trump, your trade posture has a simple premise: leverage first, deal second. I want to start with the hardest, most honest question. When do tariffs function as legitimate bargaining—and when do they become destabilizing coercion that breaks trust and investment?

Donald J. Trump: It’s legitimate when you’re getting ripped off. For years, countries took advantage of the United States. Bad deals, unfair tariffs, currency games—you name it. Tariffs are a tool. You use the tool to get a better deal. If people call that coercion, fine. It’s called negotiation. And guess what? It works.

Robert Lighthizer: Trade policy is national security policy. Tariffs are legitimate when they correct structural imbalances—predatory practices, forced technology transfer, subsidized overcapacity, chronic deficits that hollow out industries. The destabilizing part comes from pretending that “free trade” is automatically fair. It isn’t. Predictability without fairness is just predictable decline.

Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala: Tariffs can be legitimate within clear rules and transparent processes. They become destabilizing when they are applied broadly, unpredictably, and outside agreed frameworks—because then uncertainty becomes a tax on the global economy. Businesses stop investing. Smaller economies lose access. Retaliation spirals. The point of trade rules is not to stop countries from defending interests; it is to stop every disagreement from becoming a trade war.

Dani Rodrik: I think we need to be frank: tariffs can be legitimate as a domestic social contract tool. Governments must maintain political legitimacy at home. If openness creates concentrated pain and diffuse gains, backlash is inevitable. But coercion is when tariffs are used not to repair domestic legitimacy but to extract unrelated concessions and signal dominance. That invites countermeasures and accelerates fragmentation.

Jason Furman: Tariffs can be legitimate in narrow, clearly defined cases—national security, unfair trade practices—especially with evidence and a plan. They become destabilizing when they’re used broadly as a first resort, because the costs hit consumers, supply chains, and confidence. You can “win” a negotiation and still lose long-term growth if uncertainty becomes the baseline.

Gillian nods slowly, as if she’s watching the same movie from five different seats.

Gillian Tett: Good. Now the second question is what everyone in Davos is really calculating in the margins of their notebooks. Can “deal-first” trade policy coexist with predictable investment and supply-chain stability—or does the logic of leverage require permanent uncertainty to keep working?

Robert Lighthizer: It can coexist, but only if you’re honest about what stability means. The old system promised stability while allowing systematic cheating. That wasn’t stability—it was complacency. Deal-first can create predictability if it establishes durable terms: reciprocal market access, enforceable commitments, domestic reindustrialization. The uncertainty is a transition cost to reset a rigged equilibrium.

Donald J. Trump: You know what creates predictability? Knowing the U.S. is serious. When companies see we’re going to protect our workers and make good deals, they invest here. People act like tariffs are chaos. What’s chaos is letting your country get hollowed out. I’m not going to do that.

Jason Furman: The problem is that investment needs stable expectations—on costs, access, and rules. If firms believe policy can swing dramatically with each negotiation cycle, they delay decisions or diversify away from exposure. Even if your objective is fairer terms, you can design it with more predictability: clear criteria, timelines, off-ramps, and multilateral coordination where possible.

Dani Rodrik: Deal-first can coexist with stability if we define “stability” politically, not just economically. If your social contract is breaking, the economy is unstable even if markets look calm. A new trade regime that protects policy space—allowing countries to maintain labor standards, climate policies, and social cohesion—could produce deeper stability. But if deal-first becomes performative brinkmanship, it creates the worst kind: political instability abroad and economic instability at home.

Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala: Predictability is itself a global public good. Deal-making can happen inside rules—rules that allow flexibility but discourage arbitrary escalation. The danger is normalizing the idea that the strongest actor can rewrite terms at will. That forces others to build competing blocs, not because they want to, but because they must hedge. That is the path to a fragmented trading system that is less efficient and more conflict-prone.

Gillian keeps her expression neutral, but her question sharpens like a blade.

Gillian Tett: Third question. Everyone claims their approach will deliver strength. But strength has tradeoffs. What is the hidden cost of tariffs-as-leverage: inflation, retaliation, fragmentation—or is the hidden benefit a rebalanced system that actually lasts?

Jason Furman: The near-term costs are straightforward: higher prices for consumers, disruption in intermediate inputs, and retaliation that hits exporters. The longer-term cost is uncertainty, which depresses investment and productivity. The potential benefit—if you believe it exists—is a new equilibrium with less cheating and more domestic capacity. But to get that benefit, you need careful targeting and a strategy beyond the tariff itself.

Robert Lighthizer: The hidden benefit is rebuilding industrial capability and bargaining power. Retaliation is manageable if you have leverage and clarity. Inflation depends on how you implement and what you’re targeting. The larger risk is continuing a system where strategic industries migrate, critical supply chains become dependent, and you end up weaker. If you want a stable system, you must first correct the imbalance.

Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala: Fragmentation is the hidden cost that compounds. Once the world splits into separate standards, separate supply networks, separate compliance regimes, it becomes expensive to re-integrate. Smaller and developing economies pay the highest price. The hidden benefit of reform is real if it strengthens fairness and inclusivity. But if the method is unilateral escalation, the damage spreads beyond trade into trust—into the ability to cooperate on climate, health, security.

Dani Rodrik: The hidden cost is that tariff politics can become permanent—an easy tool for leaders to perform toughness. Then you don’t get rebalancing; you get a new addiction. The hidden benefit, if managed well, is restoring democratic legitimacy: people tolerate openness when they feel protected from its shocks and respected by their own institutions. If tariffs are part of a broader domestic strategy—skills, safety nets, industrial policy—they can support that legitimacy. If they’re a standalone weapon, they can erode it.

Donald J. Trump: The hidden cost of the old system was jobs and power—gone. That’s the cost nobody in these rooms wanted to talk about. I’m willing to take short-term heat to get long-term strength. And retaliation? We have the market. People want access. You make a deal, everybody wins. You don’t, then you don’t get the access. It’s very simple.

Gillian looks down at her folder, then back up—like she’s deciding whether simplicity is a strength or a risk.

Gillian Tett: Let me sum up what’s on the table. President Trump and Ambassador Lighthizer argue that leverage is the reset button—short-term disruption for long-term fairness and strength. Ngozi is warning that unilateral reset becomes systemic fragmentation and punishes the vulnerable. Dani is arguing legitimacy is the core variable—trade policy must preserve democratic stability. Jason is saying you can pursue fairness, but design matters: clarity, targeting, off-ramps.

She pauses, then asks the question that doesn’t sound academic at all.

Gillian Tett: If you had to define the difference between “leverage that reforms” and “leverage that breaks,” what is it?

Robert Lighthizer: Whether it produces enforceable reciprocity.

Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala: Whether it preserves trust and predictable rules for all—not just the powerful.

Dani Rodrik: Whether it strengthens legitimacy at home without destroying cooperation abroad.

Jason Furman: Whether it reduces uncertainty over time instead of institutionalizing it.

Donald J. Trump: Whether it gets results.

Gillian lets that last line hang, because it’s the line the whole week has been orbiting—results measured by whom, at what cost, and with what kind of world left standing afterward.

Topic 3: “No Force” — Greenland, the Arctic, and Security by Transaction

The snow outside is brighter than it should be—white glare off the mountains, like nature insisting everything is clean. Inside, the room is not clean. It’s precise. A small Davos studio with a round table, water glasses untouched, and a muted Arctic map on the wall—no labels, just ice, ocean, and coastline shapes.

Fareed Zakaria looks at the map for a beat before he looks at the people.

Fareed Zakaria: President Trump, you said you wouldn’t use force—yet you’ve put Greenland and the Arctic into the center of a security conversation. I want to start where the world’s confusion starts. If Greenland is framed as “national security,” what principle limits that logic from expanding everywhere? Where does it stop?

Fiona Hill: The principle is sovereignty—full stop. Security concerns don’t erase sovereignty. If great powers normalize the idea that “security” can justify pressure over territory or governance choices, you create a world where every neighbor becomes a potential pretext. The limiting principle has to be law plus alliance cohesion. Otherwise “security” becomes a blank check.

Donald J. Trump: It stops where it makes sense. We’re talking about national security, shipping lanes, the Arctic, resources, and a world that’s changing fast. People love to say “sovereignty” like it’s magic. The United States has to protect itself. I’m not talking about force. I’m talking about smart arrangements—things that make everyone safer and stronger.

Mette Frederiksen: It stops at the reality that Greenland is not a piece on a chessboard. Greenland has its own people, its own identity, its own democratic choices. Denmark and Greenland take security seriously—we are allies. But the principle cannot be “bigger country wants, bigger country gets.” If that becomes the rule, the world becomes unstable very quickly.

Anders Fogh Rasmussen: The limiting principle is the alliance itself. NATO is built on mutual defense, not territorial bargaining. If we start treating allies like negotiable assets, we weaken deterrence. You can talk about Arctic security all day—and we should—but it must be done through cooperation, not pressure. Otherwise you invite exactly the rival behaviors we’re trying to deter.

Mark Rutte: The logic must be bounded by shared security planning. The Arctic is strategic, yes. But the way to handle it is agreements: capabilities, basing arrangements where appropriate, investment in surveillance and infrastructure, joint exercises, clear coordination with Denmark and Greenland’s leaders. The “limit” is consent—because consent is what keeps alliances strong.

Fareed nods, then leans in.

Fareed Zakaria: So consent, sovereignty, alliance cohesion. But the world heard another signal too: transactional security. Which brings me to the next question. Is “framework talk”—the idea of a deal, an arrangement, a new structure—genuine de-escalation? Or is it the normalization of transactional territorial pressure that makes everyone nervous?

Donald J. Trump: It’s de-escalation because it’s honest. The old way was vague promises and everyone pretending the problems weren’t there. I’m saying: let’s talk about what’s real. Security is real. The Arctic is real. If we can make a framework that works—great. If people don’t want to talk, that’s their choice, but then they shouldn’t complain when the world changes around them.

Anders Fogh Rasmussen: It can be de-escalation if it’s done inside alliance processes, respecting sovereignty, and with transparency. But if it is perceived as pressure—especially public pressure—it risks doing the opposite. Allies don’t respond well to being put on the spot. And adversaries interpret alliance friction as opportunity.

Fiona Hill: “Framework talk” sounds calm, but it can be a vehicle for coercion if one side controls the terms and the threat environment. In great-power politics, offers often come with unspoken consequences. That’s what makes countries nervous: not the paperwork, the power imbalance behind the paperwork.

Mark Rutte: I think it depends on the tone and the channels. Quiet, serious diplomacy can reduce risk. Public bargaining can increase it because it forces leaders into pride positions. If we want de-escalation, we need private clarity and public unity—so rivals see coherence, not cracks.

Mette Frederiksen: For Denmark and Greenland, it cannot be a “framework” that is written about us without us. If the process respects Greenlandic self-determination and alliance cooperation, then yes, dialogue reduces tension. If it feels like a demand with a timeline, then it doesn’t reduce tension—it relocates it into the alliance.

Fareed lets the tension breathe. He glances back at the Arctic map—ice that looks static, even though it is melting.

Fareed Zakaria: Final question, and it’s the one that decides whether this becomes a footnote or a fault line. What’s the real Arctic future: deterrence stability, alliance strain, or a new bargain-driven order? And what’s the single biggest move that pushes us toward the best outcome?

Mark Rutte: The best outcome is deterrence stability through alliance unity. The move is coordinated investment: Arctic capabilities, infrastructure, surveillance, and readiness—done together, not as a bilateral surprise. When allies move in sync, the Arctic becomes less vulnerable to miscalculation and less tempting for rivals.

Fiona Hill: The Arctic future becomes bargain-driven if law and institutions are sidelined. The move toward stability is to reaffirm sovereignty and predictable rules—then build practical cooperation on top: search and rescue, environmental monitoring, deconfliction channels. Security must be strong, but it must be anchored. Otherwise you create a permanent auction of strategic geography.

Donald J. Trump: The best outcome is strength and clarity. The move is to stop pretending we can ignore strategic realities. The Arctic is not going away. Russia’s there. China’s interested. We need to be serious. If allies want stability, they should invest, commit, and recognize that the United States is carrying a big load. Fairness creates stability.

Mette Frederiksen: The best outcome is alliance stability with Greenlandic self-determination respected. The move is a three-way approach: Denmark, Greenland, and the United States working as partners—quietly, consistently, and with mutual respect. That builds security without turning people into symbols.

Anders Fogh Rasmussen: The real danger is alliance strain—because strain invites testing. The move is disciplined alliance process: decisions made with allies, not at allies. Strength is essential, yes—but so is cohesion. If cohesion breaks, deterrence weakens, and then the Arctic becomes a theater for pressure rather than cooperation.

Fareed folds his hands.

Fareed Zakaria: What’s striking is that everyone agrees the Arctic matters—and everyone disagrees on the political method. President Trump argues clarity and leverage bring stability. The others argue consent and cohesion bring stability. The risk is that each side thinks it’s preventing testing—while unintentionally inviting it.

He looks around the table, voice quiet but sharp.

Fareed Zakaria: If the Arctic is becoming the new high ground, then the choice isn’t whether it becomes strategic. It already is. The choice is whether strategy looks like alliance architecture—or like a real estate negotiation.

No one laughs. The map stays unlabeled. The implication doesn’t need labels.

Topic 4: The Board of Peace — Parallel Diplomacy or Parallel Authority?

The room they’ve been given feels like a TV studio disguised as diplomacy—soft lighting, soundproof walls, a round table that’s too perfect, and a single blank placard on the wall that could be a logo but isn’t. Outside, Davos hums. Inside, the idea on the table is new enough to make everyone slightly suspicious of their own assumptions.

Christiane Amanpour: The phrase itself is provocative: a “Board of Peace.” It sounds elegant—almost irresistible. But history is crowded with elegant ideas that failed on contact with reality. So let’s begin at the fault line. President Trump, you pitched a new body because you believe the existing system is too slow, too compromised, too performative. Does creating a new ‘peace board’ solve coordination and speed—or does it weaken legitimacy by bypassing institutions that already exist?

Donald J. Trump: The current system is slow. Everybody knows it. Meetings, committees, statements, nothing happens. People are dying. The Board of Peace is about results. You get the right people, you get them in a room, you make decisions, and you move. If it works, that’s legitimacy. The legitimacy is the outcome.

Samantha Power: Outcomes matter, but legitimacy is not optional. If you create parallel structures that answer to power rather than law, you may move quickly, but you also invite abuse. Institutions are slow for a reason: they prevent one actor’s preferences from becoming everyone else’s reality. The question isn’t only “Can we move faster?” It’s “Can we move faster without breaking the rules that keep the weak from being crushed?”

John Bolton: Let’s be honest about what this is. The UN and a lot of multilateral bodies are often ineffective because they’re built on illusions of consensus. If the President wants a new mechanism that reflects real power and can act, that’s not inherently bad. The key is that it must serve American interests first. If it becomes a committee for moral theater, it will be useless. If it becomes a tool to apply pressure efficiently, it could be valuable.

Martin Griffiths: Speed is not the same as effectiveness. I’ve seen “fast diplomacy” that ignores local realities and collapses in weeks, leaving worse violence behind. A peace mechanism must be legitimate to those who live under its decisions. If a new board accelerates attention, funding, and coordination, that could save lives. But if it bypasses humanitarian principles, excludes essential actors, or creates false promises, it could do harm at scale.

Mark Carney: I’m instinctively sympathetic to the desire for competence—systems that work. But a Board of Peace can’t be a branding exercise or a power shortcut. If it competes with existing institutions, it will fracture coordination. If it complements them—by focusing on execution, financing, and accountability—it could add value. The tension is between speed and trust. Lose trust, and you lose the very cooperation that makes speed possible.

Christiane Amanpour: That’s a clean divide: outcome-as-legitimacy versus process-as-protection. Let’s sharpen it. Suppose this board exists. It will need rules—not slogans. What governance would prevent it from becoming either performative or captured by powerful states? Who sits on it, how are decisions made, and what stops it from turning into a private club with global consequences?

John Bolton: If you want it to work, don’t pretend it’s democratic. Make it small, decisive, and aligned with the countries that actually have leverage. You want a rule? The rule is: those who can enforce peace shape the terms. That’s how it’s always been. Capture by powerful states isn’t a bug—it’s the reality. The danger is pretending otherwise and then being paralyzed.

Samantha Power: That’s precisely why governance matters. If you hard-code power, you lose moral authority, and you lose buy-in. You need transparency, oversight, and clear criteria for action: civilian protection thresholds, humanitarian access guarantees, independent monitoring. And you need representation that isn’t cosmetic—particularly for affected regions. Otherwise, you don’t have a Board of Peace; you have a Board of Power.

Donald J. Trump: Look, the problem with “oversight” is it becomes a way to stop action. You can have rules, sure—basic rules. But it has to be practical. The people on it should be people who can get things done. Not talkers. The board should be able to move fast, bring the parties together, create deals, enforce consequences if someone breaks the deal. If you can’t enforce, you’re just writing letters.

Martin Griffiths: Enforcement is important, but so is protection. If the board is not anchored in humanitarian principles, it will produce deals that look stable on paper and break human lives on the ground. Governance should include safeguards: a standing humanitarian impact assessment, red lines against forced displacement, mechanisms to guarantee aid corridors. You can move quickly and still be principled, but you must build those principles into the design, not add them later as apologies.

Mark Carney: I’d frame governance like this: clarity of mandate, constraints on scope, and accountability for outcomes. The board should have limited, defined objectives—ceasefire implementation, stabilization finance, reconstruction coordination—rather than vague “world peace” ambition. Capture happens when mandates are broad and opaque. Prevent capture by setting standards, publishing metrics, and building a coalition architecture where no single actor can rewrite terms alone.

Christiane Amanpour: I notice a pattern: everyone agrees on leverage; you disagree on what should restrain leverage. Let me push toward the part that usually breaks new initiatives: expansion. Every successful mechanism, the moment it has a win, starts to believe it has a mission. So here’s the final question. If this board claims early success in one conflict, how do you stop mission creep? And who gets a seat when the board inevitably wants to expand—more conflicts, more regions, more “peace processes”?

Mark Carney: Mission creep is a governance failure, not a moral one. You stop it with strict scope: define what the board does, define what it doesn’t do, and require supermajority consent for expansion. If the board becomes everything, it becomes nothing. The seat question should track contribution and legitimacy: those who fund, those who enforce, and those who are directly affected—balanced so the board can act without becoming unaccountable.

Samantha Power: You stop mission creep by tying authority to standards and independent evaluation. If you expand without proving you protected civilians, improved humanitarian access, and created durable outcomes, you shouldn’t expand. As for seats: affected regions must have real voice, not symbolic presence. Otherwise, you create a board that speaks about people rather than with them. That destroys the very peace you claim to build.

John Bolton: Mission creep is avoided by keeping the mandate aligned with national interest and strategic priorities. If the board becomes a global social-work project, it will fail. Seats should go to those with skin in the game and the willingness to use pressure. The world doesn’t need another talk shop. If it can’t compel compliance, it doesn’t matter who sits on it.

Martin Griffiths: But compulsion without legitimacy is unstable. A board that grows by brute force will accumulate resentment and, eventually, resistance. Mission creep is prevented by humility: recognizing that peace is local, that every context is different, and that sometimes the best action is not a new “process” but sustained protection and relief. Seats must include humanitarian expertise and conflict mediation professionals, not only political actors.

Donald J. Trump: Mission creep is easy: don’t do it. You pick the places where you can win—where there’s leverage, where the parties want a deal, where you can enforce it. If you can’t, you don’t pretend. That’s how you avoid creep. As for seats, you put the people in the room who can make the deal happen. Too many seats, nothing happens.

Christiane Amanpour: There it is—the core argument in plain language. President Trump says: choose winnable deals, move fast, enforce. Ambassador Power says: speed without legitimacy becomes abuse, and abuse becomes backlash. John says: power is the point, don’t dress it up. Martin says: protection and local reality are the difference between a pause and peace. Mark says: design the architecture—scope, standards, accountability—so leverage doesn’t become chaos.

She leans back, not satisfied—because she isn’t supposed to be.

Christiane Amanpour: Let me end with the uncomfortable truth: “peace” is the most marketable word in politics. It sells hope instantly. That is exactly why it attracts bad design and worse incentives.

She looks at Trump.

Christiane Amanpour: If the Board of Peace becomes a shortcut around institutions, it will be condemned as a power play.

She looks at Power.

Christiane Amanpour: If it becomes an institution of perfect principles with no leverage, it will be condemned as theater.

She looks at everyone.

Christiane Amanpour: The only question that matters is whether you can build a mechanism that acts quickly without becoming lawless; that wields leverage without becoming predatory; that seeks results without turning human lives into bargaining chips.

The room doesn’t feel resolved. It feels designed—like a blueprint with sharp edges, waiting for someone to decide whether it becomes a tool or a weapon.

Topic 5: Borders as Strategy — Immigration, Labor, Identity, and Power

The room for this one is quieter—not because the issue is small, but because everyone knows it detonates families, elections, and alliances all at once. A Davos side suite with soft carpet and too much glass. Outside: badges, cameras, the choreography of global confidence. Inside: the question that refuses choreography.

Bari Weiss sits forward, elbows near the table, eyes moving from face to face like she’s already reading their defenses.

Bari Weiss: Let’s not pretend. “Borders” is the issue where people smuggle three different arguments under one word: security, economics, and identity. President Trump, you framed borders as strategy—part enforcement, part leverage, part sovereignty. So here’s the first question, clean and sharp. Is border control mainly a security issue, an economic policy, or an identity signal—and which one is actually driving outcomes right now?

Donald J. Trump: It’s all three, but security comes first. If you don’t have borders, you don’t have a country. People can talk about identity—sure. People can talk about labor. But when you have millions coming in, you don’t know who they are, you don’t know what they’re bringing, you don’t know what they’ll cost. I’m for legal immigration. But illegal? No. It’s not complicated.

Alejandro Mayorkas: Security is essential, but reducing this to a single lever misses the operational truth. Border systems fail when the legal pathways are broken, the processing capacity is overwhelmed, and the incentives are unmanaged. Enforcement alone won’t fix it if the system is structurally congested. Economics and geopolitics drive flows. Identity politics can distort the response. The outcomes depend on whether policy addresses all parts of the system.

E. J. Antoni: The economic component is often downplayed. Mass illegal immigration can suppress wages for lower-skilled workers, strain public services, and shift bargaining power away from domestic labor. Yes, some industries benefit, but the gains aren’t evenly distributed. Identity matters because it shapes trust—whether citizens believe the state can govern. When people lose trust, everything becomes political combustion.

Tyler Cowen: The honest answer is that identity drives the politics and security drives the rhetoric, while economics drives much of the reality. Labor demand exists. Demographic decline exists. But the public doesn’t experience “aggregate GDP.” They experience school capacity, housing costs, cultural cohesion, and the sense of whether rules apply. Outcomes hinge on legitimacy. A policy that is economically rational but politically illegible will collapse.

Yascha Mounk: I’d emphasize democratic legitimacy. Liberal democracies can sustain openness when citizens believe institutions are competent and fair. When borders appear porous, citizens infer a deeper message: the state can’t enforce its own rules. That erodes trust. Then identity becomes a proxy battlefield. Security concerns rise because distrust rises. So yes, it’s all three—but legitimacy is the fuse connecting them.

Bari doesn’t nod yet. She’s not there to validate; she’s there to separate what sounds good from what holds up.

Bari Weiss: Second question. Everyone throws around the word “success,” but they mean different things. What does success even mean here—fewer crossings, higher wages, safer cities, social cohesion—and which metrics actually matter enough to settle the argument?

E. J. Antoni: If you want a serious metric, start with labor outcomes at the bottom: wage growth and labor participation for lower-income citizens. Add fiscal impact: net costs to local and state governments, especially education and healthcare. If those metrics are negative, “success” is a story told over the objections of the people paying the bill.

Alejandro Mayorkas: Success must include operational metrics: reduction in unlawful entries, faster processing, fewer backlogs, improved asylum adjudication speed and quality, and effective removal of those who don’t qualify—paired with expanded legal pathways for those who do. If you don’t increase throughput and legality, you simply displace the problem from one bottleneck to another.

Tyler Cowen: We should also include dynamism metrics: entrepreneurship, regional revitalization, workforce shortages filled, and long-term productivity. But I agree with the legitimacy frame: if citizens perceive disorder, the politics will implode. So you need metrics that are visible and intuitive to the public, not just to economists.

Yascha Mounk: Social cohesion matters, but it’s hard to measure without propaganda on both sides. Still, there are proxies: trust in institutions, support for democratic norms, levels of political violence, segregation patterns, and intergroup hostility. If border policy increases polarization to the point that democracy itself is threatened, then you’ve “won” a policy battle and lost the system.

Donald J. Trump: Success is simple: secure border, fewer illegal crossings, criminals out, legal immigration that benefits the country. And yes—wages go up for Americans when you stop the flood. People can make it complicated. It’s not. You enforce the law and you get control back.

Bari tilts her head slightly, like she’s testing whether “simple” is leadership or a refusal to see the system.

Bari Weiss: Final question, and it’s the one that decides the next decade. How do democracies enforce borders without radicalizing politics or breaking legitimacy? Because right now it feels like we’re choosing between chaos and cruelty, and neither is sustainable.

Yascha Mounk: The key is fairness plus competence. If citizens see a system that applies rules consistently—humane but firm—they can accept tradeoffs. If they see disorder or selective enforcement, they assume elites are gaming the system. That fuels extremism. You need credible enforcement and credible integration: language acquisition, civic expectations, anti-discrimination protections, and a clear pathway for those who meet standards.

Alejandro Mayorkas: You need layered policy: enforcement at the border, yes—but also regional cooperation to reduce push factors, faster adjudication, modernized processing, and legal pathways that match reality. Otherwise you manufacture illegality. And you have to communicate honestly: absolutes and theatrics erode trust. People must see the machine working.

E. J. Antoni: You can’t avoid radicalization by ignoring legitimate grievances. If working-class citizens feel sacrificed for cheap labor or elite ideology, they will turn to anyone who promises control. So you enforce the border, you reduce illegal flows, and you put citizens first in labor policy. Then the temperature drops. Compassion without control becomes chaos, and chaos breeds cruelty.

Tyler Cowen: The tragedy is that both sides often choose the worst rhetoric: one side romanticizes openness without governance; the other side weaponizes fear without system design. A functional democracy needs boring competence: predictable rules, consistent enforcement, and a public story that doesn’t demonize people. If you can’t tell a story that blends firmness with dignity, politics will keep rewarding extremes.

Donald J. Trump: Radicalization comes from being ignored. For years people said, “Oh, it’s fine,” while communities changed overnight and crime went up and costs went up. Enforce the border and people calm down. That’s what happens. When people feel the country is being protected, they’re not radical—they’re relieved.

Bari leans back a little, letting the room feel the collision: competence, legitimacy, identity, economics, and the primal human desire for a boundary that means something.

Bari Weiss: Here’s what I’m hearing. President Trump says enforcement restores relief and trust. Mayorkas says enforcement without system capacity manufactures illegality. Antoni says economics and wages are the neglected truth that drives resentment. Cowen says legitimacy requires visible competence and a story that avoids demonization. Mounk says democracy itself is the fragile asset, and borders are now one of its stress tests.

She looks around, voice steady.

Bari Weiss: The border debate isn’t just about who comes in. It’s about whether the state can still do the one thing it exists to do: enforce rules consistently enough that citizens accept living together.

No applause. No moral bow. Just that quiet Davos discomfort—the moment when everyone realizes the argument isn’t going away, because it isn’t only an argument. It’s a referendum on governance.

Final Thoughts by Donald J. Trump

Here’s the truth: the world has been pretending for too long. Pretending bad trade deals don’t matter. Pretending open borders don’t matter. Pretending that strength doesn’t matter. And then everybody acts shocked when people lose trust, when countries get taken advantage of, when rivals push and push because nobody pushes back.

If you want peace, you need credibility. If you want fairness, you need enforcement. If you want stability, you need rules that actually mean something—and consequences when they’re broken. That’s not “harsh.” That’s how you prevent bigger problems later.

This series is going to show you the mechanics: how leverage works, where it helps, where it can backfire, and what kind of world it creates if everyone starts playing the same game. Some people will love it. Some people will hate it. But nobody should say it doesn’t matter—because it does. Davos felt it. Allies felt it. Rivals felt it.

And at the end of the day, I’m not interested in speeches that sound good. I’m interested in outcomes that last.

Short Bios:

Donald J. Trump — U.S. President whose Davos presence dominated the week, framing global issues through leverage, deals, border enforcement, and hard-security signaling.

David Ignatius — Washington Post columnist known for measured, inside-the-system moderation that teases out incentives, red lines, and unintended consequences.

Gillian Tett — Financial Times editor with an anthropologist’s eye for hidden power structures, translating trade, markets, and institutions into human motives.

Fareed Zakaria — Global affairs host and author who excels at framing geopolitical disputes as competing systems—then pushing for clarity on first principles.

Christiane Amanpour — Veteran international journalist and interviewer, relentless about legitimacy, accountability, and the human consequences behind statecraft.

Bari Weiss — Commentator and interviewer who drives direct, high-friction conversations on culture, sovereignty, and the political psychology beneath policy.

Ian Bremmer — Political risk analyst who treats geopolitics as incentives and constraints, pressing leaders to convert slogans into executable strategies.

Stephen Walt — Realist international relations scholar focused on alliances, deterrence, and how status contests and credibility drive conflict.

Anne Applebaum — Historian and writer on authoritarianism and democratic resilience, emphasizing legitimacy, norms, and the dangers of power-as-performance.

Mark Rutte — European security leader associated with alliance cohesion and deterrence, stressing predictability and unity during high-stakes signaling.

Robert Lighthizer — Trade strategist and former U.S. negotiator known for a tariffs-first worldview that treats trade as power and industrial survival.

Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala — WTO Director-General focused on rules-based trade, warning about fragmentation and advocating reforms that protect smaller economies.

Dani Rodrik — Economist arguing for “smart” interdependence and democratic policy space, balancing globalization with domestic legitimacy.

Jason Furman — Economist and policy adviser emphasizing growth, consumer impacts, and the design details that separate effective trade tools from economic drag.

Fiona Hill — Russia and security expert known for clear-eyed warnings about sovereignty, coercion, and the risks of personalistic diplomacy.

Mette Frederiksen — Danish leader emphasizing alliance cooperation, Greenlandic self-determination, and Arctic security handled through consent, not pressure.

Anders Fogh Rasmussen — Former NATO Secretary General focused on deterrence and alliance process, warning that public bargaining can invite adversary testing.

Samantha Power — Former diplomat and humanitarian advocate emphasizing civilian protection, legitimacy, and safeguards against power-driven “peace” shortcuts.

John Bolton — Hardline national security thinker, skeptical of multilateralism, arguing power and enforceability matter more than process.

Martin Griffiths — Humanitarian and conflict-response leader emphasizing on-the-ground realities, aid protection, and the limits of “fast diplomacy.”

Alejandro Mayorkas — Former homeland security leader focused on operational border capacity, lawful pathways, and system-level management.

E. J. Antoni — Economist emphasizing wage impacts, fiscal costs, and the political consequences of perceived elite indifference to border enforcement.

Tyler Cowen — Economist and commentator who focuses on dynamism, legitimacy, and “boring competence” as the antidote to polarization.

Yascha Mounk — Political scientist on democratic stability, arguing border competence and fairness are now core tests for liberal democracy.

Leave a Reply