|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

What if David Morehouse debated remote viewing with top researchers and skeptics?

Introduction by David Morehouse

Remote viewing explained is not a parlor trick, and it is not a religion. It is a disciplined attempt to access information about a target you cannot normally perceive, while using protocol to reduce the two greatest enemies of truth: suggestion and self-deception. If you came here hoping for certainty, I will disappoint you. If you came here willing to do the boring work, stay humble, and let results speak louder than belief, then you are in the right place.

Across these five topics, we do not hide from the hard questions. We define what remote viewing is and what it is not. We get honest about how testing fails, even when nobody is lying. We talk about the viewer’s internal battlefield, because imagination can feel identical to signal when you want the answer badly enough. We draw bright ethical lines, because the moment you start using impressions as verdicts, people get hurt. And we end where we should begin, with the only standard that matters in the long run: repeatability.

(Note: This is an imaginary conversation, a creative exploration of an idea, and not a real speech or event.)

Topic 1: What Remote Viewing Really Is (and isn’t)

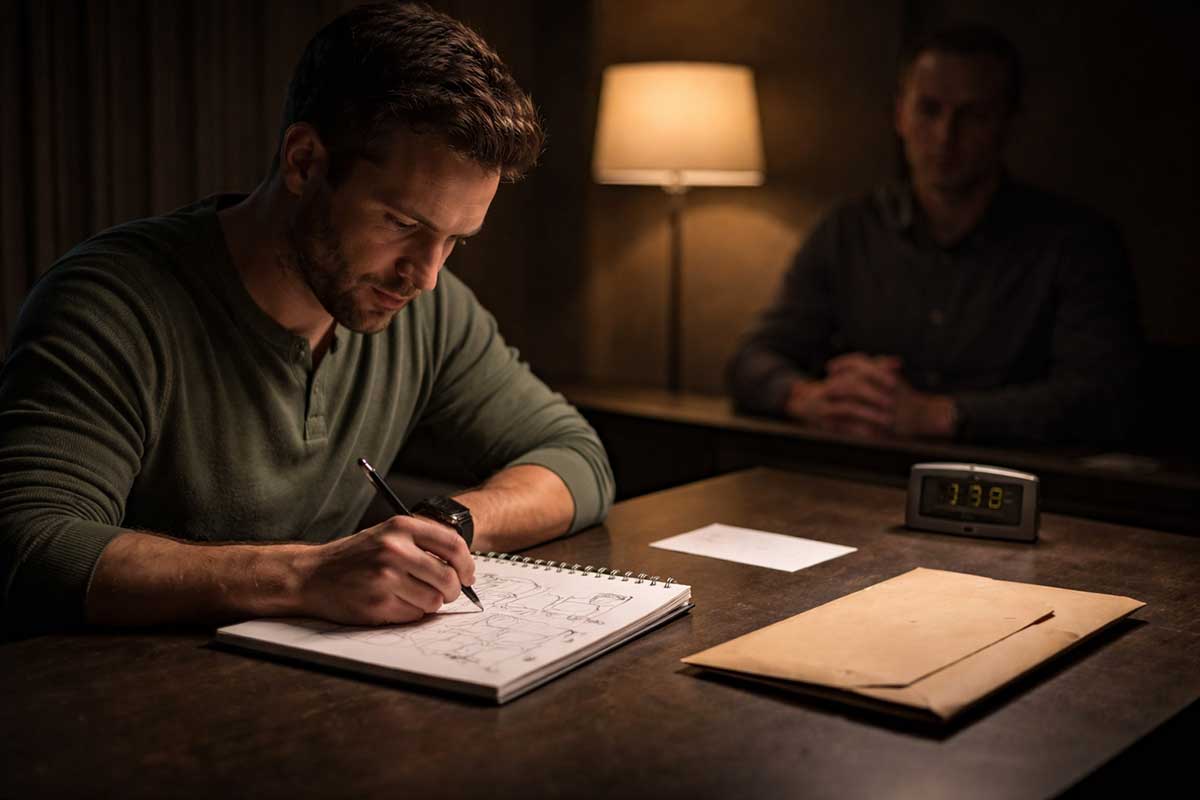

Lex Fridman: We’re sitting in a quiet room with no screens on, no cues, no “helpful” hints in the air. Just a question that keeps coming back like a chorus: what is remote viewing, really, and what is it not. David, let’s start with you. If you had to define it in a way that doesn’t lean on romance or reputation, what would you say?

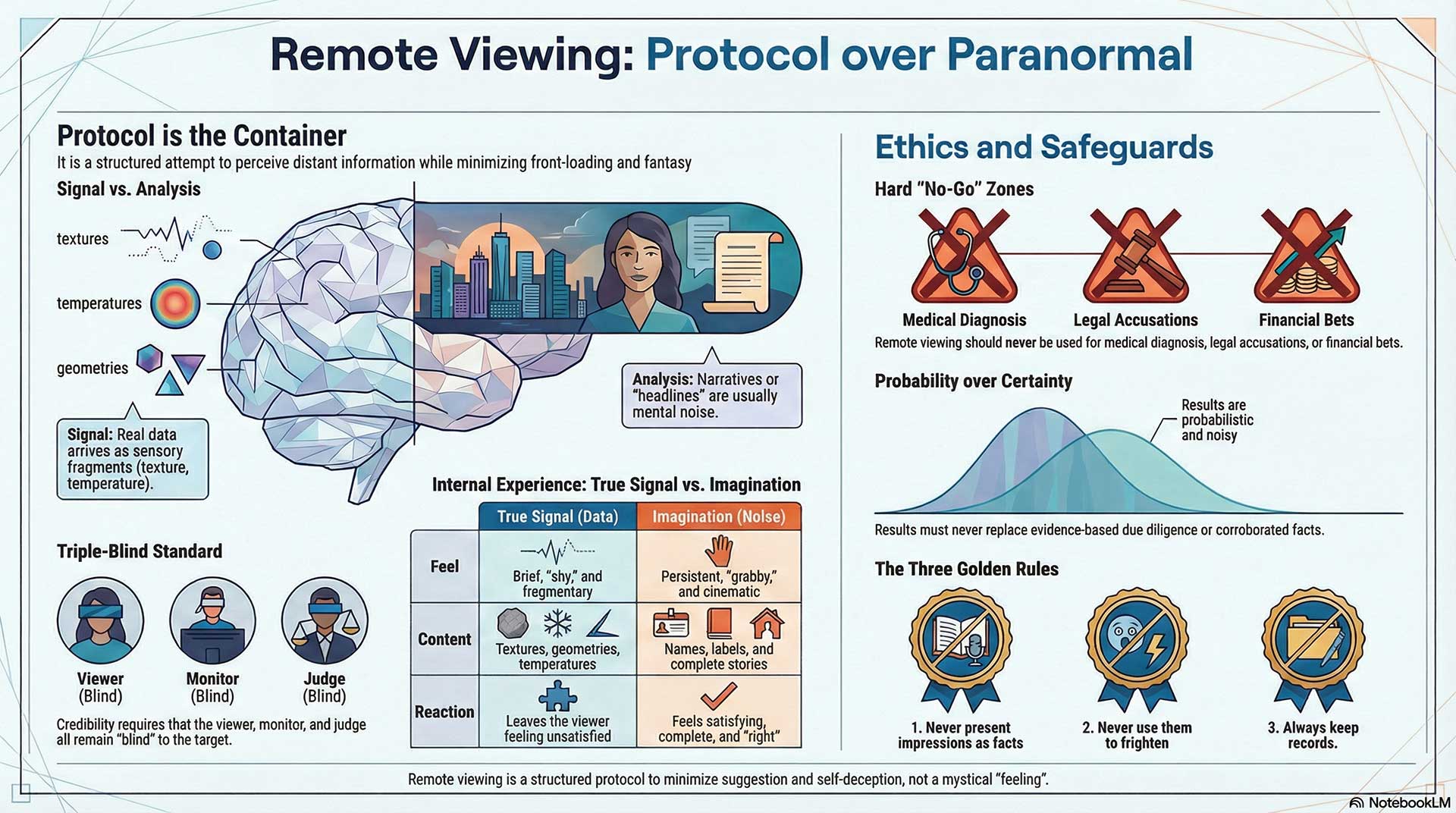

David Morehouse: Remote viewing is a protocol. That’s the first thing people miss. It’s not “I had a feeling” or “I saw a vision.” It’s a structured attempt to perceive information about a target you do not have normal access to, while minimizing front-loading and fantasy. If you remove the protocol, you’re left with intuition, imagination, or storytelling. Those can be meaningful, but they’re not remote viewing.

Ray Hyman: Notice what David did there. He made it about procedure, not about paranormal certainty. That’s smart, because the biggest problem in this space is category drift. People call everything remote viewing: gut feelings, dreams, mediumship, déjà vu. Then they cite the entire pile as evidence for the one thing they want to claim.

Ingo Swann: And yet, procedure alone is not the soul of it. Protocol is the container. The thing inside the container is a human capacity to register faint impressions that are not obviously sourced from the five senses. When I worked, I did not experience it as “I am psychic.” I experienced it as “I am perceiving.” Perception is a slippery word, but it matters. Because if it’s perception, you can train it, refine it, and you can also contaminate it.

Russell Targ: I agree with that framing. In our early work, what mattered was whether information could be obtained under conditions that eliminate ordinary explanations. The question was never “Is this mystical.” The question was “Does it produce statistically meaningful results when you remove sensory leakage.” That’s the hinge.

Jessica Utts: And the moment you start using words like “statistically meaningful,” half the audience leans in and the other half rolls their eyes. But this is the difference between an anecdote and evidence. If remote viewing is real as a phenomenon, it should show up as an effect across many trials, not just memorable stories. The protocols are there to make the signal measurable.

Lex Fridman: Let me push the definition edge a little. If a person says, “I pictured a bridge and later I found out the target was a bridge,” that sounds like a hit. But if they didn’t have blinding, tasking, judging, and feedback controls, it could also be coincidence. So here’s the real question underneath: what separates remote viewing from intuition, cold reading, and educated guessing in practice, not in marketing language?

Ray Hyman: Blinding and independence. If the viewer can be influenced, even subtly, by the person who knows the target, your “hit” is suspect. Humans are suggestion engines. We detect micro-cues. We also retro-fit memories. People forget their misses and canonize their wins. So the separation is not spiritual sincerity. It’s control of information flow.

David Morehouse: That’s fair. And I’ll add one more: remote viewing is not about being right in a cinematic way. It’s about fragments. Texture. Temperature. Motion. Structure. You’re often dealing with partial descriptors that later can be matched. That’s why the judging matters. If you let the viewer see the target before scoring, you’ve already destroyed the test.

Ingo Swann: And do not confuse “fragments” with “vagueness.” There is a difference. A fragment can be precise. “Vertical,” “metal,” “echoing,” “crowds below,” “wind at height,” can point somewhere. The danger is when the mind says, “Ah, that must be the Eiffel Tower,” and then you are no longer perceiving. You are naming. That naming is usually where the fantasy begins.

Russell Targ: Ingo is describing what we saw. The best viewers tended to describe, not declare. They would give sensory and spatial elements. The analysts and judges would do the matching. When you ask viewers to be prophets, you get performance and anxiety. When you ask them to be observers, you get data.

Jessica Utts: And there’s a statistical point here. If you have a forced-choice design, like “Which of these four images is the target,” chance is 25 percent. If you consistently beat that under proper blinding, you have an effect. Not a proof of mechanism, but an effect. The separation from intuition becomes: does it replicate, and does it beat chance in controlled conditions.

Lex Fridman: I want to make this concrete. Imagine you all had to agree on what a “clean hit” looks like. Not the kind of hit that convinces your fans, but one that would make a skeptical scientist pause. What does that look like?

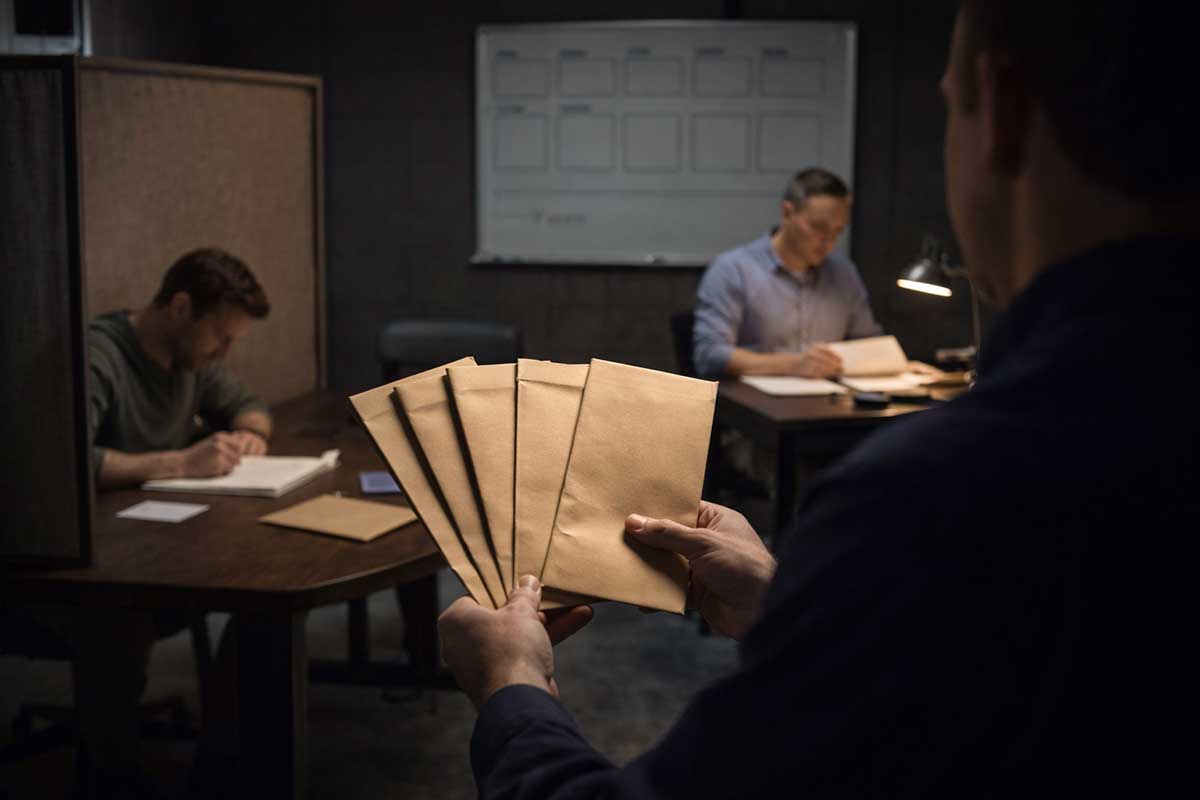

Russell Targ: Properly blinded target selection, independent judging, and scoring done before feedback. The viewer produces a transcript. Judges match transcript to possible targets. If the correct target is ranked first at a rate that’s reliably above chance over many trials, that’s clean.

Ray Hyman: Add pre-registration. Decide your scoring method before you start. Decide what counts as success before you see results. Otherwise, you can torture data until it confesses. Also, the target pool has to be constructed to prevent generic matches. If any sketch can “fit” anything, you’ve built a self-fulfilling system.

Jessica Utts: I’d also include effect size. “Above chance” can be statistically significant but practically small. If the effect is tiny, it may be real but not useful. A clean hit would be both statistically credible and meaningfully informative. Something that reduces uncertainty, not just something that can be rationalized after the fact.

David Morehouse: And from the practitioner side, a clean hit is one where the transcript contains elements that are specific enough that you wouldn’t casually generate them. Not “There’s water,” because Earth has a lot of water. More like “I sense a curved boundary with rhythmic impact,” and it turns out to be a stadium with waves of cheering. But I agree, you still need controls. Specificity without controls is still just a story.

Ingo Swann: I’m going to be blunt. Many “hits” people brag about are not clean. They are emotionally clean, because they felt true. But clean as evidence, no. A clean hit must be unromantic. It must survive boredom. It must survive repetition. If you can’t do it again, you have a tale, not a skill.

Lex Fridman: That leads to the last part of this first topic. Let’s assume, just for the sake of exploration, that some form of remote viewing does produce real information sometimes. What does it seem best at describing? Where does it break?

Jessica Utts: The data from various studies suggests it’s often better at broad characteristics than fine-grained identifiers. Patterns, general structure, maybe function. Exact names, dates, or numbers are much harder. That’s consistent with an effect that is noisy and probabilistic.

Russell Targ: Yes. It can be surprisingly good at gestalt: a sense of the overall scene, motion, purpose, “this is a place where people gather,” or “this is industrial.” It’s less reliable for crisp details that require symbolic labeling.

Ray Hyman: Or, alternatively, it is good at producing material that humans are good at matching after the fact. We are pattern matchers. If you give me ten vague descriptors, I can fit them to many targets, especially if I know the target set. So what it’s “best at” might be partly an artifact of how we judge it.

David Morehouse: That’s why I keep coming back to training and discipline. The viewer needs to stay in description mode and avoid analysis. Analysis feels satisfying, but it’s the fastest way to be wrong with confidence. When it works, it feels like a thin signal: a texture, a pressure, a geometry. When you try to force it into a headline, it collapses.

Ingo Swann: And it breaks when you want it to be a god. When you demand certainty, you get theater. When you accept that perception can be partial, you can work with it. A viewer is not an oracle. A viewer is a human instrument, and human instruments have drift.

Lex Fridman: So for Topic 1, the shape that’s forming is this: remote viewing is claimed as an information-gathering process under controls, not a vibe. Clean hits require boredom-proof procedures, not charisma. And even if there’s something real, it seems to speak in textures and structures more than in neat labels.

Alright. Next, I want to take you into the weeds where the fights live: blinding, judging, scoring, and the places where the whole thing quietly breaks without anyone intending to cheat.

Topic 2: Protocol Wars: Blinding, Scoring, and Repeatability

Lex Fridman: Same quiet room, same rule. No theatrics. If remote viewing is going to be taken seriously, it has to survive the most boring thing on Earth: proper controls. So let’s go straight into it. If you had to name the single control that matters most for credibility, what is it?

James Randi: Double blinding. And not “we think it was blind.” Real blindness where nobody in the room, nobody interacting with the viewer, nobody scoring in a flexible way can leak the target. People underestimate how easily information seeps in, even through tone, timing, enthusiasm. The easiest way to fake a miracle is to leave one tiny doorway open.

Lyn Buchanan: I agree that blinding is essential, but I’ll sharpen it. The most important control is preventing front-loading. In training, people want to know what they’re doing, because uncertainty feels uncomfortable. But that hunger for context is exactly how you poison the session. If the viewer knows anything, even “it’s a location in Europe,” you just changed the whole game.

Edwin May: From a research perspective, pre-specification is the critical piece. Decide the target pool, decide the judging method, decide the scoring criteria before the first session is done. Otherwise you are doing archaeology, not science. You are digging through the rubble of data trying to find something that looks like treasure.

Joe McMoneagle: The most important control is separating the viewer from anyone who knows the target. Period. If the monitor knows, you get subtle steering. If the analyst knows, you get confirmation bias. If the judge knows, you get motivated matching. When remote viewing is done operationally, everyone wants it to work. That wanting itself becomes contamination.

David Morehouse: For me, it’s feedback discipline. People hate this answer because it’s less sexy than blinding, but if you don’t have honest feedback, you can’t calibrate the instrument. Viewers learn by noticing what signal feels like, what noise feels like, and what their personal traps are. Without clean feedback, you train delusion.

Lex Fridman: I love that you all picked different “most important” controls, which kind of proves the point: there are many failure points. Let’s talk about the quiet failures. Not fraud. Not intentional cheating. The accidental ways this breaks down even when everyone is sincere. Where do you see it happen most?

Edwin May: The biggest accidental breakdown is flexible analysis after the fact. People do a session, then they hunt for a target that fits. Or they adjust their scoring method once they see the transcript. That is not malicious. It is human. The mind wants coherence. It wants a win. That is why pre-registration matters.

Joe McMoneagle: Another big one is target pool design. If your targets are too similar, you’re testing confusion, not perception. If your targets are too broad, anything can match something. You need targets that are distinct and a judging process that does not allow “creative interpretation” to become the scoring method.

James Randi: My favorite accidental breakdown is the “helpful” assistant. Someone says, “I’m going to keep this organized,” and suddenly the viewer is receiving little clues. Or the target setter picks a target that has emotional meaning to the team and everybody’s energy changes. You can call it contamination, you can call it cueing, but it’s the same thing. It ruins the experiment.

David Morehouse: I’ve seen breakdowns in the moment of translation. The viewer gets a sensory impression and immediately names it. “It feels like water” becomes “It’s the ocean.” “It feels like height” becomes “It’s a skyscraper.” That leap is where the story hijacks the data. It’s not cheating, it’s the brain trying to be useful. But in protocol terms, it’s a failure.

Lyn Buchanan: I’m going to call out something uncomfortable: training culture. In some groups, people reward dramatic sessions more than accurate sessions. If a student learns that emotional performance gets applause, they will unconsciously give emotional performance. They’ll start adding narrative. You can feel it in a transcript. It reads like a movie. Real sessions often read like weird sensory fragments, because that’s what it is.

Lex Fridman: That’s a fascinating point. Incentives shape the output. Now I want to ask the question that everyone argues about but rarely designs well. If you had to build a modern test that both believers and skeptics would respect, what would it look like?

James Randi: It would be simple. Pre-registered. Independent. Cash reward if you can do it reliably. The viewer is given a target number. The target is selected by a process no human can influence after selection. The viewer produces a transcript. The transcript is matched to a set of decoys by judges who have no stake in the outcome. If remote viewing is real, it should show up like any other claimed ability under proper conditions.

Edwin May: I would add rigor without turning it into theater. The target pool should be large and locked. The judging should be blind and preferably algorithm-assisted, but human judges can work if they’re independent and trained. The scoring should be decided in advance. Most importantly, you need enough trials to estimate the effect. One dramatic “win” proves nothing.

Lyn Buchanan: And you need viewers who are actually trained, not people dragged in off the street and asked to do something they’ve never done. Skeptics often set up tests that are designed to fail by ignoring skill acquisition. If you want a fair test, you recruit competent viewers, you standardize their method, and you keep the protocol clean. Then you let the data speak.

David Morehouse: I’d build it with two layers. One that tests pure perception and one that tests operational usefulness. The first layer is classic: blind targets, decoys, scoring. The second layer asks: does this information reduce uncertainty for a decision maker? Not “did you name the object,” but “did you provide descriptors that helped someone identify the correct target better than chance.” That’s closer to how it was used.

Joe McMoneagle: I’d also address the reality of variability. A fair test measures individuals over time. Some days you’re on, some days you’re not. If you pretend every session should be perfect, you’ll declare failure too quickly. But if you allow endless excuses, you never test anything. So you set a performance threshold in advance: over X sessions, you must exceed Y accuracy.

Lex Fridman: Let me press all of you on one thorny detail. The moment you introduce judging, skeptics say “subjective matching.” And the moment you force objective answers, practitioners say “that’s not how the signal arrives.” How do we bridge that?

Edwin May: You bridge it by using multiple scoring methods at once, all pre-registered. Rank-order judging plus quantitative feature scoring. And you report everything, not just what flatters the outcome.

James Randi: Or you bridge it by refusing to accept “It can’t be tested” as an answer. If a claim can’t be tested, it can’t be used to make decisions. That doesn’t mean it’s false. It means it’s not evidence.

Lyn Buchanan: The signal often is qualitative, but qualitative does not mean sloppy. You can break a target into features: textures, geometries, sounds, temperatures, motion. Then you score features. If people want numbers, give them numbers that reflect the actual data.

David Morehouse: This is where humility matters. Remote viewing is not a magic trick. It’s not supposed to impress. It’s supposed to collect impressions under controls. If we can’t agree on what counts as a hit, we shouldn’t be selling certainty. We should be building better tests.

Joe McMoneagle: And we should be honest about what it can and cannot do. It can sometimes describe aspects of a target. It is not a replacement for evidence. It’s not a courtroom tool. It’s not a medical tool. If you define the use case properly, the testing becomes cleaner.

Lex Fridman: So the picture coming into focus is this: credibility lives in boring discipline. Blinding, separation, pre-registration, target pool design, judging that does not wiggle, and incentives that reward accuracy over drama. If you build a test that respects both the need for controls and the nature of the data, you at least get to an honest question.

Next, I want to go inside the viewer’s mind, because even with perfect protocol, the biggest contaminant might still be internal: imagination, emotion, fear, ego, and the strange way confidence can help and distort at the same time.

Topic 3: The Viewer’s Mind

Participants: David Morehouse, Cindy Riggs, Lyn Buchanan, Paul H. Smith, Ray Hyman

Moderator: Lex Fridman

Lex Fridman: Topic 3 is where it gets personal. Even if the protocol is perfect, the viewer’s inner world can still sabotage everything. So let me start with the question most people secretly care about. In the moment, while you’re doing it, how do you tell the difference between signal and imagination?

Lyn Buchanan: The simplest answer is also the least satisfying. You don’t know in the moment. Not with certainty. You learn your internal texture. Signal tends to arrive clean, brief, almost shy. It has a different feel than analysis. Analysis has momentum. It grabs the wheel. Signal taps you on the shoulder. So I train people to write the tap, not the story. When you start narrating, you are usually gone.

Cindy Riggs: I agree with the texture idea, but I approach it through energy. To me, imagination has a kind of personal flavor. It feels like me. Signal feels like it arrived from outside my normal mental stream. There’s a neutrality to it, like a packet. But I also want to say this carefully because I do multiple modalities. Remote viewing is supposed to be structured perception. Channeling and mediumship are different. If I’m doing RV, I’m not asking for a personality to speak. I’m listening for impressions.

Ray Hyman: That distinction is important, but it’s also where people get sloppy. What you’re all describing are introspective feelings. Those feelings can be compelling, but they are not reliable indicators of truth. Humans routinely mistake the vividness of an image for accuracy. The brain is excellent at producing convincing internal experiences that have nothing to do with external reality. That’s why you need external scoring, not internal certainty.

Paul H. Smith: Ray’s right to warn about the trap. The internal sense of confidence can be totally misleading. But he’s missing the practical part. If you’re going to do the work at all, you need a method to manage your own mind. In CRV-style approaches, we treat raw impressions as data points and we aggressively label analysis as analysis. You can literally write “AOL” and move on. That’s not a spiritual claim. It’s a psychological tool to stop the mind from hallucinating certainty.

David Morehouse: And the truth is, the signal is often not cinematic. It’s not a voice telling you the answer. It’s pressure, temperature, motion, density, texture, geometry. The imagination wants a headline. The signal gives you fragments. So one way you know you’re still in signal is that you are slightly dissatisfied. It feels incomplete. When it feels too complete, too satisfying, that’s often the ego writing the script.

Lex Fridman: That’s interesting. Dissatisfaction as a marker of honesty. Cindy, you said something that matters for our series. You work with experiences that many skeptics would group together. So let’s go straight at it. Where is the line between remote viewing, mediumship, and channeling? Should they be separated, or do you think they blur into each other?

Ray Hyman: Before Cindy answers, I’ll frame why I care. When you blur categories, you remove falsifiability. If remote viewing is “protocol-based perception,” you can test it. If it becomes “a spirit told me,” then the standard of evidence changes dramatically. The danger is not just scientific confusion. The danger is that people start making serious decisions based on untestable stories.

Cindy Riggs: I actually agree with the danger. That’s why I separate them in my own practice. Remote viewing is target-based and structured. Channeling is allowing a being or a consciousness stream to communicate through you. Mediumship is communication with deceased human personalities. They can feel different. Remote viewing is more like receiving impressions and assembling them carefully. Channeling has a relational quality, like a dialogue. But can people drift between them without realizing it? Absolutely. That’s why discernment is the whole game.

Paul H. Smith: In training, we try to keep it clean. If you’re doing remote viewing, you do not want to be negotiating with entities, asking questions, or inviting anything. You want a sterile channel, in the engineering sense. The viewer is an instrument. You gather data. You score it. If someone wants to interpret it spiritually, that’s their personal choice, but the method should stay disciplined.

Lyn Buchanan: I’ll put it bluntly. The biggest failure I see is people who want the outcome so badly that they will accept any internal event as “information.” They’ll start mixing dreams, symbols, feelings, and then declare it remote viewing because the word sounds authoritative. If you want RV credibility, treat it like a craft. Like marksmanship. You don’t call every loud sound a bullseye. You score the target.

David Morehouse: I’m going to speak to the middle. I’ve met viewers who are intensely spiritual and viewers who are intensely mechanical, and sometimes they get similar results. That suggests the underlying phenomenon, if there is one, might not care about our narrative. But for public clarity, you absolutely separate them. Otherwise, remote viewing gets swallowed by everything that cannot be tested, and then it’s dead as a serious practice.

Lex Fridman: Cindy, you also talk a lot about safety, asking whether an entity is “from the light,” and so on. I know that’s your world, and I’m not trying to blend it into RV. But it does raise a shared issue: how do you keep the mind honest when it wants certainty? Which leads to the third question. Training seems to matter, but confidence seems to matter even more. How do you build real confidence without building false certainty?

David Morehouse: Feedback. Hard feedback. You do sessions, you score them honestly, and you look at your patterns over time. Confidence should be earned like a pilot earns it. Not from one successful landing, but from hundreds, including rough weather. The worst thing for a viewer is a few early dramatic hits that convince them they’re infallible.

Ray Hyman: I’ll add something unpopular. You build confidence by building skepticism toward yourself. Your default stance should be: I am biased, I am error-prone, my memory is unreliable, and I am motivated. If your method does not assume those things, it is not protecting you. Real confidence comes from procedures that prevent you from fooling yourself, not from believing harder.

Lyn Buchanan: That’s actually compatible with training. In CRV, we teach you to distrust analysis. Not because analysis is evil, but because analysis pretends to know. You can absolutely use analysis later, after the session, but during collection it’s poison. So confidence becomes this odd thing. It’s not confidence in your conclusions. It’s confidence in your process. I can trust that I stayed in structure. I can trust that I didn’t front-load. I can trust that I recorded impressions without decorating them.

Paul H. Smith: Exactly. The beginner’s problem is that they think confidence means “I’m right.” It doesn’t. It means “I did the method and I accept the outcome.” That keeps you sane. And then you iterate. People also need to understand that performance varies. If you pretend variability means “it’s fake,” you’ll quit prematurely. If you pretend variability means “mysterious forces,” you’ll drift into excuses. The healthy middle is measurement: track your results, track your conditions, track your errors.

Cindy Riggs: I’m going to bring it back to the human experience. Confidence is a choice, but it has to be an informed choice. For people developing intuition, they often don’t trust themselves because they’ve been trained not to. So the first step is: I will treat my impressions respectfully, but not worship them. I will test them where I can. I will be humble where I can’t. And I’ll say one more thing: fear distorts perception. If you are terrified of being wrong, you will over-control and block impressions. If you are terrified of being judged, you will perform. So confidence is also nervous-system regulation. Calm, grounded, present. That’s when perception tends to be cleaner.

Ray Hyman: Cindy, I appreciate that you’re emphasizing humility and testing. That’s where many people in adjacent fields fail. They sell certainty. They don’t measure. They don’t publish misses. If someone wants to practice this responsibly, they should keep records, allow independent scoring, and accept that feeling certain is not the same as being correct.

David Morehouse: And that’s where the practitioner and the skeptic can actually shake hands. We can disagree about the ultimate explanation and still agree about the safeguards. Discipline is kindness. It protects the viewer from ego and the client from fantasy.

Lex Fridman: So what we’ve got at the end of Topic 3 is something like a shared code. Signal feels fragmentary and slightly unsatisfying. The mind wants headlines, and that’s where it lies to you. Categories matter because testability matters. Confidence should be confidence in process, not confidence in being right.

Next topic gets sharper. If someone claims they can perceive information beyond the senses, that claim becomes tempting. People will use it for money, love, health, guilt, criminal accusations, even grief. That’s where ethics stops being theoretical.

Topic 4: Ethics and Harm When Psychic Information Becomes Dangerous

Participants: David Morehouse, Joe McMoneagle, Annie Jacobsen, Steven Novella, Jessica Utts

Moderator: Lex Fridman

Lex Fridman: This topic is the one that makes everybody uncomfortable for the right reasons. Because if remote viewing is even occasionally useful, it becomes tempting. And temptation is where people get hurt. So I want to begin with a hard boundary question, not a theoretical one. Even if remote viewing worked better than critics think, what should it never be used for?

Steven Novella: Medical decisions and legal accusations. Full stop. Anything where a wrong guess can lead to real harm, delayed treatment, ruined reputations, wrongful arrests. The problem is not only that remote viewing might be wrong. It’s that humans overweight confident narratives. A dramatic reading can overpower common sense and evidence. That is exactly how people get hurt.

Joe McMoneagle: I’ll echo legal and medical. Also anything that replaces basic due diligence. If someone wants to use it as a pointer, maybe, but it cannot become the deciding factor. In operational contexts, you treat it as one input among many, and you never forget it can be wrong. The moment you forget that, you turn it into a weapon.

Annie Jacobsen: I’ll add a category that people don’t like to talk about. National security decisions. When people get enamored with extraordinary methods, they start making extraordinary leaps. History shows that institutions can become superstitious under pressure. If you start using psychic claims to justify policy, you’ve created a permission structure for bad decisions that will not be accountable.

Jessica Utts: I agree with the high-stakes areas, but I want to be precise. Some people will use it regardless. So the ethical question becomes, if it is used, how do we minimize harm. The answer is to forbid certainty language and require transparency about error rates. If someone is going to offer it, they should state what the evidence supports and what it does not. Most harm comes from overstating confidence.

David Morehouse: For me, the line is decisions that alter someone’s life trajectory without corroboration. If a remote viewer says “your spouse is cheating” or “your child is in danger” or “you have a disease,” that is a grenade. Remote viewing is not built for that. It’s descriptive, fragmentary, and it is easy to be wrong with conviction. So I say no to diagnosis, no to criminal accusations, no to relationship verdicts, and no to financial bets presented as certainty.

Lex Fridman: So everyone agrees there are no-go zones. But here is where it gets messy. People still use these things for missing persons, grief, closure, “is my partner faithful,” “should I take this job,” and so on. The next question is about protection. If someone is practicing remote viewing or any adjacent intuitive work, how do you protect the client from dependency and how do you protect yourself from overreach?

Joe McMoneagle: You begin by refusing the role of authority. The practitioner must not become the decider. You make it clear that what you provide is impressionistic and uncertain. You encourage the person to seek normal avenues first. And you keep records. If you are serious, you track your accuracy. Most people avoid tracking because they don’t want to face their misses.

Jessica Utts: The record-keeping point is huge. Dependency thrives in ambiguity. If you don’t quantify outcomes, clients can believe you’re always right because they remember the emotional moments. Ethical practice requires you to publish your uncertainty. You can literally show a base rate. “In similar tasks, I perform around X.” Even if the number is imperfect, it disciplines the story.

Steven Novella: I would go further. You also need to protect clients from your own cognitive biases. People doing these practices often believe they are immune to self-deception. They are not. The ethical approach is to adopt safeguards like pre-commitment. You write down the impressions before any feedback. You separate tasking from viewing. You avoid talking the client into interpretations. And you should never use it to create fear because fear is a control mechanism.

David Morehouse: Overreach often happens when a practitioner tries to be a hero. “I’m going to solve it. I’m going to fix it. I’m going to save you.” That mindset pushes you into analysis and drama. So I train toward restraint. Give the data, clearly labeled. Do not interpret it as destiny. If the client wants meaning, they can find meaning, but you do not hand them a verdict.

Annie Jacobsen: I’m going to bring in the social layer. Overreach is not just personal. It’s incentivized. People make more money and gain more status when they sound certain. Platforms reward confidence, not caution. The ethical practitioner is swimming against the current. So you need structural guardrails. Written disclaimers. Clear scope. Refusal policies. And honestly, you need a community that criticizes you when you drift.

Lex Fridman: That’s interesting. Community accountability rather than lone genius. Let me tighten the question. Suppose a client is vulnerable. They’re grieving, or terrified, or desperate. They want you to be certain. They want you to tell them what to do. What does ethical uncertainty look like in practice, in the actual words you say?

Jessica Utts: Ethical uncertainty sounds like this: “Here is what I perceived. Here is how I produced it. Here is how often this method is wrong. Here are alternative explanations. Here is what you should do next using normal evidence.” It’s not just “I might be wrong.” It’s operational. It gives them a pathway that does not rely on you.

Steven Novella: And it includes a refusal to amplify delusions. If someone is spiraling, you do not feed the story. You don’t say “Yes, the universe is sending you a sign that your neighbor is dangerous.” You say “I can’t help with that, and you should talk to a professional.” Ethical uncertainty includes saying no.

Joe McMoneagle: It also includes recognizing the difference between a hint and a claim. If I say “I get a sense of water nearby,” that is not “Your loved one is in a lake.” The practitioner has to keep the language at the right altitude. Vague descriptors stay descriptors. They do not become accusations.

David Morehouse: I’ll make it concrete. If I ever say anything that could create fear, I slow down. I say “Do not take action based only on this.” I insist on corroboration. I ask, “What evidence do you already have.” And if they have none, I treat it as noise. Because the harm of a false alarm is real, and it damages trust in the person’s own judgment.

Annie Jacobsen: Ethical uncertainty also means not laundering your impression into legitimacy by borrowing authority. People love to cite intelligence agencies, government programs, secret research. That turns an impression into a myth. The myth becomes persuasive. The ethical move is to strip away mythology, not add to it.

Lex Fridman: I want to challenge you, David and Joe. People hear “military, CIA, operational” and they assume it must have been reliable. Skeptics then say, “If it was reliable, it would still be used openly.” How should a responsible practitioner talk about those histories without turning them into either propaganda or dismissal?

Joe McMoneagle: By being honest about variability and context. It was never a magic machine. It was one tool in a toolbox. Sometimes it was useful. Sometimes it wasn’t. You don’t turn that into a fairy tale. You also don’t pretend it never happened. You talk about it like any imperfect human method that occasionally produced actionable clues.

David Morehouse: Exactly. You don’t claim omniscience. You don’t claim it replaces evidence. If you frame it as “we could see everything,” you’re lying. If you frame it as “it was all nonsense,” you might also be lying. The ethical line is humility. “Sometimes there were results that looked real, and we tried to structure the process to reduce error.”

Steven Novella: Even that must be paired with acknowledging how easy it is to misinterpret “useful.” Intelligence work is full of ambiguous inputs. If you deliver ten vague reports and one seems to match later, people call it a success. That is not proof. So ethically, you should separate “people believed it helped” from “we demonstrated an effect under rigorous controls.” Those are different claims.

Jessica Utts: Right, and this is where language matters. The ethical practitioner says, “There is debate about the evidence. Here is what studies show, here is what critics argue, here is what we do to reduce self-deception.” You treat the audience like adults. You don’t sell certainty.

Annie Jacobsen: And you keep the stakes visible. When organizations are under stress, they will grasp at methods that promise advantage. That’s why ethics cannot be an afterthought. It must be built into the practice. Otherwise, the practice will drift toward whatever rewards attention, money, or power.

Lex Fridman: Let’s land this topic with a practical compact. If someone watching this wants to explore remote viewing without hurting themselves or others, what are the three ethical rules you’d want them to tattoo on their brain?

David Morehouse: One: Never present impressions as facts. Two: Never use it to accuse, diagnose, or frighten. Three: Keep records and let reality correct you.

Steven Novella: One: Do not replace evidence-based decision-making. Two: Build safeguards against self-deception, especially blinding and pre-commitment. Three: Refuse to play authority over vulnerable people.

Jessica Utts: One: Measure your performance honestly. Two: Communicate uncertainty with numbers and plain language. Three: Always offer next steps that do not depend on you.

Joe McMoneagle: One: Stay descriptive, not declarative. Two: Use it only as a supplement, never as the sole basis for action. Three: Be willing to be wrong and say so out loud.

Annie Jacobsen: One: Beware the incentives that reward certainty. Two: Do not mythologize your own practice. Three: Remember that the cost of being wrong is not abstract, it’s human.

Lex Fridman: That’s the heart of Topic 4. If remote viewing is anything at all, it’s not a license to bypass reality. The ethical center is restraint, measurement, and refusing to turn uncertainty into a weapon.

Next, we go to the strangest place, the place where even skeptics sometimes pause. If an effect exists, what does it imply about consciousness and reality, and what kind of evidence would settle it in a way that doesn’t devolve into religion or ridicule.

Topic 5: If Remote Viewing Works, What Does That Mean About Reality

Participants: David Morehouse, Ingo Swann, Russell Targ, Donald Hoffman, David Chalmers

Moderator: Lex Fridman

Lex Fridman: This is the topic where people either get defensive or poetic. Let’s try for neither. Just clean thinking. If remote viewing sometimes works, even a little, what does it imply about consciousness, time, and space?

Russell Targ: It implies that consciousness is not confined to the brain in the way we usually assume. At minimum, it suggests there can be access to information that is not mediated by the known senses. That doesn’t force a particular spiritual conclusion. But it challenges a strict “mind is only inside the skull” model.

David Chalmers: I’m sympathetic to the “challenge,” but I’m cautious about “implies.” A replicable effect would imply that our current models are incomplete. It wouldn’t automatically imply a specific metaphysics. The history of science is full of surprising effects that later found natural explanations. Still, if information is accessed beyond standard channels, it does put pressure on materialist intuitions.

Donald Hoffman: I would go further. Our perception is not a window onto objective reality. It’s an interface, a user interface. If consciousness is fundamental, then what we call space and time may be part of the interface, not the underlying truth. Remote viewing, if genuine, would be a crack in the idea that we are locked inside the interface.

Ingo Swann: You’re all circling something I felt as a practitioner. The target is “over there,” yet impressions arrive “in here.” The question is: where is “there” and where is “here?” If the mind can register information across distance, then distance is not the barrier we imagine it is. It doesn’t mean physics is wrong. It means our model of mind is too small.

David Morehouse: From my side, it implies humility. We might be dealing with a human capacity that exists on the edge of what we can measure cleanly. If it’s real, it’s not a superpower. It’s more like a faint radio station. The implication isn’t “we are gods.” The implication is “we don’t know what we are.”

Lex Fridman: Let’s make it sharper. Suppose RV exists as a weak but real effect. Is it a trainable skill anyone can learn, or does it depend on rare traits?

David Morehouse: Anyone can improve their sensitivity to the signal, but not everyone will become a top performer. That’s true in music, athletics, and perception tasks. Training helps, discipline helps, but there’s variability. Some people have a temperament for it. Some don’t.

Ingo Swann: Training matters, but the culture around it matters more. If you train people to chase certainty, they will hallucinate. If you train them to tolerate ambiguity and collect impressions cleanly, you will get better data. It’s not that some people are “chosen.” It’s that some people can stay quiet inside.

Russell Targ: Empirically, there are differences between individuals, but that doesn’t mean it’s rare in principle. Many people show some above-chance performance in certain tasks. The practical question is whether the effect is strong enough to be useful, and under what conditions.

Donald Hoffman: If consciousness is fundamental, then everyone has access in principle. The limitation might not be “ability.” The limitation might be how tightly the interface constrains us. Training could be learning to loosen the interface rules, gently, without destabilizing function.

David Chalmers: I’ll add a philosophical caution. “Trainable” can mean two things. It can mean you can improve performance. Or it can mean you can reliably get results at will. Many human capacities are trainable in the first sense but not controllable in the second. If RV is real, it may remain probabilistic even in experts. That would fit the “weak signal” framing.

Lex Fridman: Now I want to ask the most practical and most political question. What evidence would actually settle this for the public? Not for true believers or true skeptics, but for the reasonable middle.

Russell Targ: A large-scale, multi-lab replication with strict protocols and pre-registered analysis. Not one lab. Not one charismatic teacher. Multiple groups, independent, transparent. If the effect shows up consistently, it becomes part of the scientific conversation.

David Chalmers: I agree. Add open data, open methods, and a design that separates mechanism questions from effect questions. We don’t need to know how it works to know whether it works. But we do need to rule out leakage, bias, selective reporting, and flexible scoring.

David Morehouse: I’d also want real-world usefulness tests that don’t encourage nonsense. Something like: can remote viewing help an independent analyst select the correct target from a set at above-chance rates in a way that’s practically meaningful. If you can’t turn it into anything measurable, it’ll stay a religion.

Donald Hoffman: A fair test should also respect the nature of the data. If impressions are qualitative, build scoring that handles qualitative data without allowing endless reinterpretation. A lot of fights here are not about reality. They’re about measurement mismatch.

Ingo Swann: And I would add: the public will never be “settled” by one perfect study. People will argue forever. What will change minds is a combination of careful research and careful practice that produces repeatable demonstrations without showmanship. If you need drama to persuade, you’ve already lost.

Lex Fridman: There’s one more layer that people avoid because it’s awkward. If RV works, even a little, it invites exploitation. It becomes a market. It becomes a belief system. It becomes an identity. How do you prevent “a real effect” from turning into a cultural disease?

David Morehouse: You keep it boring. You keep it measured. You keep it humble. You don’t sell it as destiny. You teach record-keeping, protocol, and restraint. And you repeat the ethics: never accuse, never diagnose, never frighten.

Russell Targ: You emphasize that uncertainty is not failure. It’s part of the phenomenon. If you demand certainty, you’ll get fraud or delusion. If you accept probability, you can do honest research.

David Chalmers: Culturally, we should distinguish two things: curiosity and authority. It’s fine to explore strange possibilities. It’s not fine to claim authority over others’ lives based on them. The ethical problem is authority, not curiosity.

Donald Hoffman: And we can also say: even if there is an effect, it doesn’t automatically give you a better moral compass. Perceiving information is not the same as wisdom. Wisdom is how you use what you think you know.

Ingo Swann: Exactly. The greatest danger is not that remote viewing is false. The greatest danger is that humans will use it to inflate themselves. If you want to explore perception beyond the senses, the first discipline is not a technique. It is character.

Lex Fridman: Let me try to summarize Topic 5 without turning it into a slogan. If remote viewing exists as an effect, it nudges us to expand our model of mind. It does not automatically endorse a single metaphysics. It may be trainable but remain probabilistic. And the only path to public credibility is boring replication, transparent methods, and ethical restraint.

Final Thoughts by David Morehouse

Here is the simplest truth I can offer. If remote viewing is nothing, then strict protocol still teaches you something priceless about your mind. It teaches you how quickly confidence turns into story, and how easily story turns into certainty.

If remote viewing is something, even a weak something, then the responsibility is even heavier. You do not get to use it to scare people. You do not get to use it to accuse people. You do not get to replace evidence with vibes. You treat it as a tool that can fail. You measure your work. You show your misses. You stay descriptive, not declarative. You keep it boring on purpose.

Because the real test is not whether you can get a hit once. The real test is whether you can pursue the unknown without lying to yourself or hurting anyone else while you do it.

Short Bios:

David Morehouse is a prominent remote viewing instructor and former U.S. Army officer known for popularizing Coordinate Remote Viewing style training for civilians. He’s best recognized for framing remote viewing as a disciplined protocol rather than a mystical gift.

Cindy Riggs is a psychic medium and trans channel who also teaches intuitive development. She describes her work as blending structured practices like hypnosis and energy work with strong emphasis on discernment and client safety.

Lex Fridman is a long-form interviewer and podcast host known for calm, methodical conversations on science, philosophy, and human performance. He’s often used as a moderator archetype because he keeps debates rigorous without turning them hostile.

Ingo Swann was a pioneering figure in modern remote viewing and is frequently associated with the early development of structured approaches to the craft. He is known for emphasizing perception, discipline, and the dangers of premature interpretation.

Russell Targ is a physicist and early researcher linked to foundational lab work exploring remote viewing under controlled conditions. He is best known for arguing that the key question is whether an effect appears reliably under proper blinding.

Jessica Utts is a statistician known for evaluating parapsychology research from a methodological and evidence-based perspective. She is often cited for focusing on effect size, replication, and clear standards for what data can and cannot claim.

Ray Hyman is a psychologist and leading skeptical critic of paranormal claims, especially around experimental design and cognitive bias. He is valued in debates for pressing on leakage, judging subjectivity, and the difference between vivid experience and reliable evidence.

Joe McMoneagle is one of the most well-known operational remote viewers associated with U.S. government era remote viewing work. He is often described as pragmatic, emphasizing uncertainty, discipline, and using results only as one input among many.

Edwin May is a researcher associated with later-stage remote viewing program era methodology and analysis. He is known for focusing on pre-registration, scoring rigor, and separating interesting stories from measurable effects.

Lyn Buchanan is a remote viewing trainer closely associated with Coordinate Remote Viewing instruction and skill development. He is known for practical training language, especially around avoiding analysis and keeping sessions clean.

James Randi was a famous stage magician and skeptic who challenged paranormal claims with a focus on fraud controls and test design. He is widely referenced for pushing the idea that extraordinary claims must survive airtight protocols.

Paul H. Smith is a remote viewing teacher and writer associated with structured CRV-style methods and training. He is known for explaining remote viewing as a learnable craft while stressing process discipline and error tracking.

Annie Jacobsen is an investigative journalist known for deep reporting on national security, intelligence history, and institutional incentives. In panels like this, she often represents the perspective of how extraordinary claims can shape policy and public belief.

Steven Novella is a neurologist and prominent science communicator known for emphasizing evidence-based thinking and consumer protection. He often focuses on where claims can cause harm, especially in medical and legal contexts.

Donald Hoffman is a cognitive scientist known for arguing that perception functions like an interface rather than a direct view of objective reality. He’s often used in consciousness discussions to explore what unusual perception claims might imply philosophically.

David Chalmers is a philosopher of mind best known for rigorous work on consciousness and the “hard problem.” In debates like this, he tends to separate questions of evidence from questions of metaphysical interpretation.

Leave a Reply