|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Neil deGrasse Tyson:

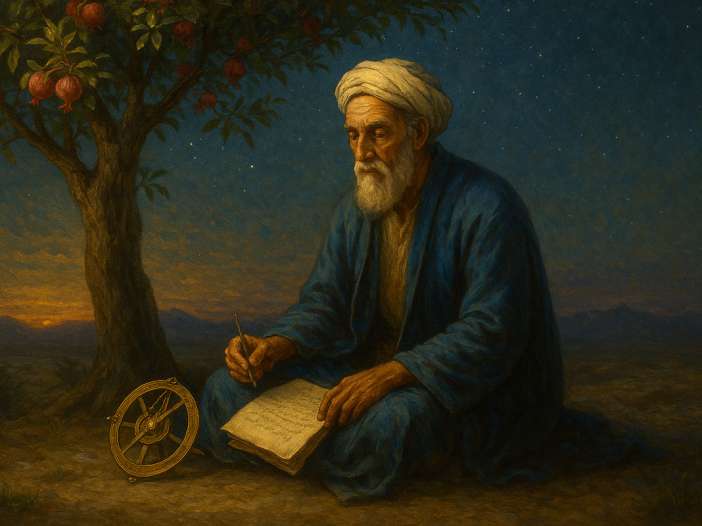

When we gaze into the night sky, the same stars that bewildered our ancestors still shine upon us. Omar Khayyam, born nearly a thousand years ago in Nishapur, was one of those rare minds who did more than wonder—he measured, calculated, and questioned the heavens themselves. As a mathematician, he refined algebra into a language of precision; as an astronomer, he reformed time itself with a calendar more accurate than the one we use today.

And yet, Khayyam was not content with equations alone. He reached beyond numbers into poetry, using the quatrain as a vessel for doubt, joy, love, and rebellion. He dared to ask if eternity was certain, if paradise was real, and if perhaps the fleeting taste of wine, the company of a friend, or the glance at a night sky held more truth than promises of the afterlife.

Omar Khayyam reminds us that science and poetry are not opposites but complementary ways of seeing. He invites us to live fully in the brief span we are given, and to celebrate both the clarity of reason and the mystery of existence.”

(Note: This is an imaginary conversation, a creative exploration of an idea, and not a real speech or event.)

Chapter 1: Early Education and the Burden of Knowledge

The air of Nishapur carried a strange mix in those days — the fragrance of mulberries, the metallic tang of ink, and the ever-present dust of the road that seemed to weave the city into the desert beyond. I remember walking with Omar when he was still a boy, his steps quick, his hands already stained black with ink, his mind darting far ahead of both of us.

He had been born into a time of both brilliance and unease. Nishapur was alive with scholars, calligraphers, astronomers, and philosophers, but it was also a city watched carefully by the eyes of orthodoxy. The Seljuk dynasty wanted knowledge, yes, but not the kind of questions that threatened to unseat certainty. And already Omar was asking the kinds of questions that made elders shift uncomfortably in their robes.

I first saw him at the home of a tutor, bent over Euclid’s Elements. His lips moved silently, as if tasting the flavor of each proof. When he looked up, his eyes were not those of a boy reading for memorization—they were the eyes of someone arguing with the stars themselves.

“Omar,” the tutor said, gently shaking his head, “it is enough to know the demonstration. Do not pull apart the heavens.”

But Omar could not be satisfied. That night, under the mulberry tree, he told me, “Why must I accept what others call eternal? Euclid says the lines are infinite, but what if the universe itself curves and bends? Will his truths still stand then?” His words were fire, and his hands trembled as he spoke them, as though afraid his thoughts might burn his very skin.

I reminded him, “Knowledge is a river, Omar. Drink slowly, or it will drown you.”

He laughed, though there was no mirth in it. “If it must drown me, let it. What better death than in pursuit of truth?”

By day, Omar studied mathematics, absorbing the works of al-Khwarizmi and al-Biruni. By night, he slipped into the language of poetry, shaping quatrains that whispered of mortality, love, and the fleeting nature of joy. He showed them only to me at first, embarrassed, as though confessing a private weakness.

“I can master the cube and the sphere,” he said, “but I cannot master the heart. Perhaps these verses are my rebellion against the tyranny of numbers.”

There was something restless in him, a hunger too large for the narrow paths carved by tradition. While other boys his age were content to memorize holy texts or recite the patterns of the stars, Omar wanted to know why—why the stars wandered, why numbers obeyed strange invisible laws, why death stalked every man yet made life taste sweeter.

One evening, he dragged me up to the roof of his family’s house. The night sky stretched above us, endless, jeweled, serene. He lifted a finger toward the constellation of Orion. “They tell us these stars are fixed in crystal spheres, eternal and perfect. But I see them wander. If the heavens themselves can move, why should we believe anything is fixed forever?”

I had no answer. I only placed my hand on his shoulder and said softly, “Trust your eyes, Omar. But trust your questions more.”

He fell silent, but I saw how deeply the words sank into him. His gaze returned to the stars, not in reverence but in defiance, as though he had already made a pact with the universe: he would not look away, no matter how blinding its truths might be.

The following year, his reputation spread. Teachers praised his brilliance, but their praise was tinged with unease. Too curious, too relentless, too unwilling to stop where tradition demanded silence. “He has no patience for boundaries,” one scholar muttered. “One day, it will cost him.”

Perhaps it already had. I could see the loneliness settling on him like a cloak. His peers respected him but did not befriend him. His questions frightened them; his brilliance isolated him. I became his confidant not because I understood all he pursued, but because I did not fear to stand beside him while he reached.

One winter, as snow dusted the city walls, Omar showed me a small lamp he had taken apart. Its flame burned weakly, flickering. He stared at it for a long time, then whispered, “I want to be like this light. Small, perhaps, but strong enough to hold back the darkness.”

I did not tell him then what I feared—that the brighter a flame burns, the sooner it draws the wind’s hunger.

But I understood in that moment that Omar’s destiny would never be an easy one. He was not built for comfort, nor for obedience. He was built to question, to pierce, to dismantle illusions even if it left him standing alone in the cold.

And as we left the lamp to gutter in the shadows of his study, I knew I was not only his friend—I was becoming the witness to a journey that would change not only his life, but the very way the world measured time, space, and the fleeting sweetness of wine upon the tongue.

Chapter 2: Reforming the Persian Calendar

The summons came one spring morning, carried on parchment sealed with the crest of Sultan Malik-Shah. Omar read it once, then again, his brow furrowing deeper with each line.

“The Sultan wishes me in Isfahan,” he murmured, half to himself, half to me. “To join a council of scholars. To reform the calendar.”

I leaned closer. “The calendar? But the stars already mark the year, and the imams already bless the months. Why does a king trouble himself with time?”

Omar’s lips curved into something between amusement and dread. “Because the harvest fails when the months do not align with the sun. Because armies march under banners of misplaced seasons. Because kings need certainty, even if the heavens themselves shift.”

That evening, he sat under the mulberry tree with his astronomical tables spread before him, the ink of countless nights smudged into his fingertips. His eyes darted across the figures. “The Julian reckoning drifts by a day every 128 years. A small mistake, perhaps, but small mistakes in the heavens become great errors on the earth.”

The journey to Isfahan was long, across deserts where the wind carried sand like knives, through towns where gossip clung to travelers like dust. When at last we arrived at the Seljuk court, the grandeur of it silenced even Omar for a time. Marble halls, gilded lamps, men of power seated in velvet, their words heavy as stone.

The council of scholars gathered—astronomers, mathematicians, jurists, each eager to leave his mark. Yet it was Omar who spoke least. He listened, pen scratching quietly as the others argued, their voices echoing off the walls like thunder. Days turned to weeks, weeks to months. Outside, Isfahan bloomed with gardens and fountains, but Omar scarcely left his chamber.

One night, I found him hunched over a globe, his face pale with exhaustion. “I have it,” he whispered. “A reckoning so precise it will not drift for thousands of years. The Jalali calendar will hold the sun to its rightful course. No more wandering days. No more false equinoxes.”

His voice should have carried triumph, but instead it carried weight. I asked him why.

“Because truth is not safe,” he said. “Each equation that brings us closer to the heavens pulls us further from the certainties men cling to. The Sultan will praise me today, but tomorrow? Tomorrow another ruler may curse me for daring to measure eternity.”

The day of presentation dawned bright. In the great hall, Omar stood before Malik-Shah, the scroll of his calculations unfurled like a river of ink across the floor. He spoke clearly, steadily, as courtiers leaned in, their eyes wide, their brows furrowed. When he finished, the Sultan rose, his laughter booming through the chamber.

“By Allah,” Malik-Shah declared, “this man has chained the sun itself!”

Applause erupted, but Omar only bowed his head. That night, when the court feasted, he slipped away to the gardens, where fountains whispered under moonlight.

I found him there, staring into the water. “Why do you not celebrate?” I asked.

He dipped his hand into the pool, scattering the moon’s reflection. “Because I have not chained the sun. I have only measured its shadow. And men do not forgive shadows when they reveal truths they would rather not see.”

His words chilled me more than the night air. Even in triumph, Omar carried the burden of doubt—the knowledge that every discovery cast him further into solitude, every triumph sharpened the knives of suspicion.

Yet, as the years passed, the Jalali calendar endured, its precision astonishing even the skeptics. And still, Omar walked the gardens with ink-stained hands and restless eyes, already searching for the next question to tear open the sky.

Chapter 3: Mathematics and the Shadows of Orthodoxy

The years after the calendar reform brought Omar both renown and unease. His name was spoken with reverence among scholars from Samarkand to Baghdad, yet in the markets and mosques, there were whispers: He peers too far into the secrets of God. He asks what no man should ask.

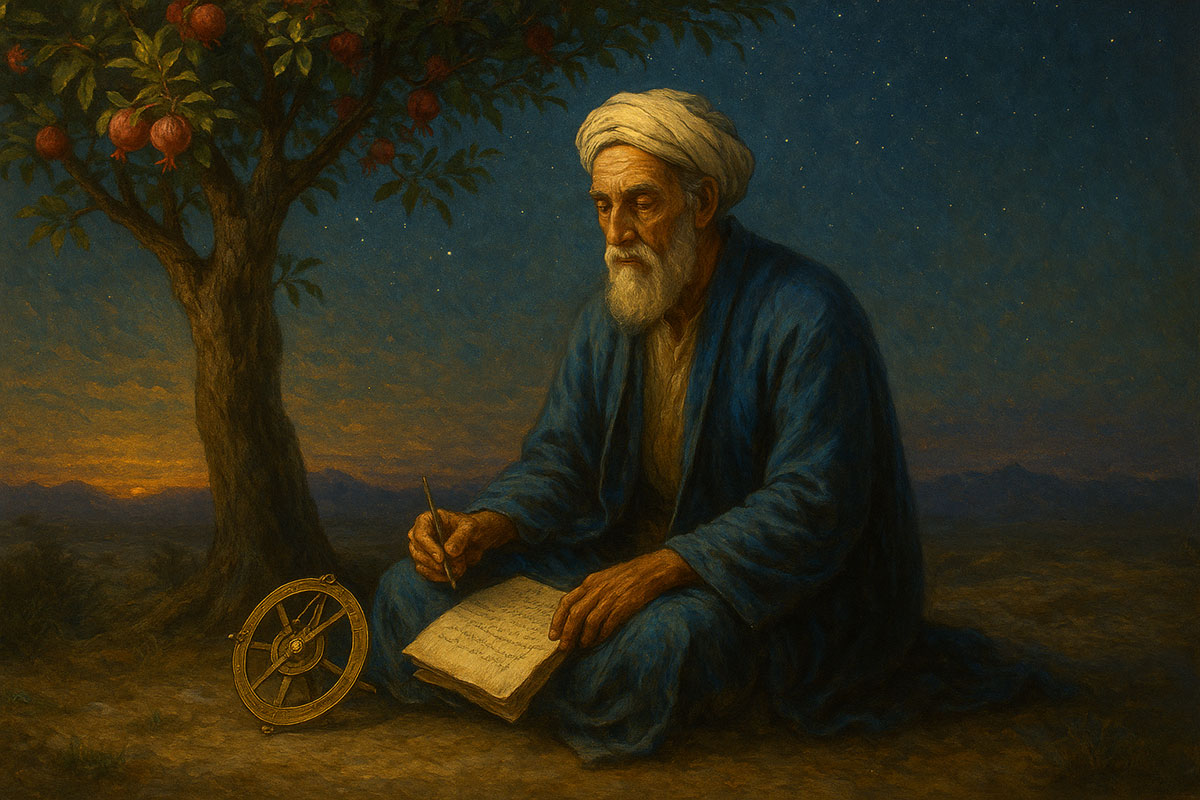

By then, I often found him bent over wax tablets and parchment, his study crowded with instruments: astrolabes, compasses, polished spheres of brass. His hands, always stained with ink, moved with quick, restless energy as he carved equations into the margins of treatises.

One evening, he summoned me to his chamber. “Look,” he said, pointing at a page scrawled with dense diagrams. “Cubic equations. For centuries, men have feared them—too unwieldy, too resistant to reason. But what if we do not attack them with numbers alone? What if we draw them? Geometry can tame what arithmetic cannot.”

On the parchment, I saw parabolas and intersecting lines. At their crossings, he marked the solutions that had eluded mathematicians for generations. His eyes gleamed with quiet triumph, though his voice remained steady.

“It is not just about solving problems,” he continued. “It is about seeing differently. The world is not only numbers—it is shapes, movements, symmetries. Mathematics is a language, and we have spoken only half of it.”

I marveled, yet I also felt the shadow that hung over his words. For in the madrassas, scholars clung to inherited knowledge like a shield. Innovation was tolerated only if it bowed before tradition. Anything more was seen as arrogance, even blasphemy.

“Will they accept this?” I asked quietly.

He smiled, weary. “Some will. Others will call me a sorcerer. But what does it matter? Truth is not less true because it frightens men.”

Not long after, a cleric came to visit, his robes dark, his tone sharper than courtesy required. He studied Omar’s pages, then closed the book with deliberate force.

“You play with numbers as if they were toys,” the cleric said. “But the order of the world is not yours to unravel. Beware, Omar. Those who dig too deep into the mysteries of God may find themselves buried beneath them.”

When the man had left, I saw Omar’s hands trembling—not with fear, but with fury. “Do you hear it?” he hissed. “They speak as though truth were a locked chest, theirs alone to guard. But the heavens are no man’s possession! The stars shine for anyone who dares to look up.”

That night, he walked with me through the silent streets of Nishapur. Snow dusted the rooftops, and the air smelled of smoke from the hearths. He spoke softly, almost to himself.

“They fear what they cannot control. But I—” He stopped, staring at the snowflakes dissolving on his sleeve. “I fear something greater. That we will spend our lives reciting old words while new truths pass us by, unseen, unspoken. That the light will go out because no one dared to carry it forward.”

I knew then that Omar’s battle was no longer with numbers or the stars. It was with the guardians of silence, those who confused preservation with stagnation. His mathematics was not merely calculation—it was rebellion. Each line he drew across a page was a crack in the walls that sought to contain human thought.

And though he laughed when we spoke of wine or love, though he scribbled quatrains mocking fate, I saw the cost in his eyes. For every discovery brought him closer to brilliance—and closer to isolation.

Chapter 4: The Philosopher’s Doubt

By the time Omar entered his middle years, the shadows of suspicion had thickened around him. His work in mathematics and astronomy was admired in secret, cited quietly in schools and whispered about in courts. But in the bazaars and the mosques, he was no longer just a scholar — he was the man who asked too many questions, the one who held his gaze too long upon the stars.

And so, when his voice could not rise in the madrassa, it found another home: in verse. In quatrains. Simple, sharp, almost careless in their form, yet carrying a weight that no polished treatise could bear.

I remember the first time he read one to me aloud. We were seated in his garden at dusk, the scent of jasmine rising in the warm air. He poured a glass of wine, lifted it against the fading light, and recited:

“A jug of wine, a loaf of bread — and thou

Beside me singing in the wilderness —

Ah, wilderness were paradise enow.”

He smiled faintly after speaking it, but his eyes were searching mine. “Do you see? It is not just a jest. It is rebellion, hidden in simplicity. They want me to believe paradise is only after death. But why must I not taste it here, with bread, with wine, with friendship?”

I felt the weight of his defiance. Each quatrain was a spark cast against a forest of dry wood. Some heard in his verses the laughter of a skeptic, others the weariness of a man who had seen through all illusions.

Yet, in private, I knew the verses came not from arrogance but from longing. Omar wrestled with God, with fate, with the emptiness of the grave. He was a believer and an unbeliever all at once, tormented by the possibility that both faith and doubt might be traps.

Often, he spoke in paradoxes. “If there is no afterlife,” he told me one night, his voice low, “then let us drink and laugh, for tomorrow we die. But if there is one, will the Almighty scorn us for treasuring the brief gift He gave us here? Tell me, which God would be so small as to begrudge His children joy?”

I had no answer. I only listened, as I always had, watching his fingers tighten around the wine cup, as though it were both an anchor and a weapon.

And yet, for all his doubt, Omar never ceased searching. He read philosophers with the same hunger he read the stars, chasing meaning through scrolls of Aristotle, through the poetry of Ferdowsi, through the whispers of Sufis who claimed the heart knew what reason never could. He admired them, but he did not join them. Their certainty was too neat, their answers too complete.

One winter evening, after a long silence, he murmured, “Perhaps life is not about finding truth, but enduring its absence. Perhaps wisdom is learning to drink from an empty cup and call it enough.”

Those words stayed with me. For in them I saw both his greatness and his wound: Omar could not lie to himself. And so he lived caught between heaven and earth, between prayer and laughter, between the silence of the stars and the song of the wine.

And it was in that tension — that restless honesty — that the Rubáiyát was born.

Chapter 5: The Solitude of Wisdom

The years of court and council faded behind him, like a city glimpsed through the dust of a long journey. Omar returned to Nishapur, not as the brilliant reformer of the Sultan’s calendar nor as the mathematician whose treatises crossed empires, but as a man seeking quiet.

He lived simply in his later days. His home was modest, his garden tended by his own hands. Visitors still came—students eager to sit at his feet, travelers curious about the famed astronomer-poet—but he welcomed few. “The noise of men deafens me,” he once told me with a faint smile. “I would rather listen to the silence of the stars.”

And so he walked the garden paths at dusk, his robes brushing against the lavender, his eyes always tilted upward, even as age clouded them. In one hand, he still carried a notebook. In the other, sometimes a cup of wine. His steps were slower, but his mind never rested.

One evening, I found him sitting by the pond, the reflection of the moon wavering on its surface. He turned to me and said softly, “Do you think the universe notices us? Or are we no more than shadows passing over shadows?”

“You have given it your life,” I reminded him. “The stars will remember you, even if they cannot speak.”

He chuckled, the sound half-bitter, half-tender. “And yet, men will argue over what I believed more than over what I proved. They will say I was a skeptic. Or a believer. Or a drunkard. Or a saint. They will clothe me in garments I never wore.” He dipped a hand into the water, shattering the moon’s reflection. “Perhaps that is fitting. A man is only ever partly known, even to himself.”

In those final years, he wrote less but spoke more. Short verses slipped from his lips, distilled wisdom, fragments of longing. Some were playful, others cut like a blade.

Once, as we watched autumn leaves scatter across the garden, he murmured:

“Ah, make the most of what we yet may spend,

Before we too into the dust descend.”

There was no defiance in his voice anymore, no rage against heaven. Only acceptance, calm and unshakable. He had spent a lifetime measuring time, yet now he surrendered to it, as one surrenders to sleep.

When illness finally came, he did not curse it. He lay on his bed by the open window, the scent of blossoms drifting in. On the table beside him rested a copy of the Qur’an, a flask of wine, and a stack of old papers filled with equations. Faith, doubt, and reason—side by side, as they had always been within him.

His last words to me were not of mathematics, nor poetry, nor even God. He grasped my hand and whispered, “Do not let them silence the questions. Promise me.”

And then he was gone, leaving behind not certainty, but a legacy of wonder.

The Jalali calendar endured, precise beyond its age. His algebraic insights opened doors for generations. His Rubáiyát, carried far from Persia, whispered across centuries, teaching lovers and skeptics alike that life, however brief, is still worth toasting with bread, wine, and song.

And I—I remained his witness, remembering the boy who once stood on a rooftop, pointing to the stars, daring them to reveal their secrets.

Final Thoughts By Jorge Luis Borges

In every quatrain of Omar Khayyam, we encounter a labyrinth of time. His verses circle around eternity, not with certainty, but with the fragile beauty of doubt. I think of him as a poet of both faith and heresy, for he stood between two infinities: the infinite stars above and the infinite questions within.

What is most remarkable is that Omar Khayyam was not trapped by the centuries in which he lived. His voice slips past walls of empires and dogma, reaching us as if he wrote yesterday, as if he whispered to us in the solitude of our own thoughts. His Rubáiyát is a mirror in which we see our own fleeting joys, our inevitable mortality, our thirst for meaning.

In Khayyam’s poetry, wine is more than wine, and the cup more than clay—it is existence itself, raised in defiance against silence. He teaches us not to conquer the unknown, but to embrace it. And so, as we close his story, we find not an ending, but an eternal conversation between a man, the stars, and the mystery of being.

Short Bios:

Omar Khayyam

Omar Khayyam (1048–1131) was a Persian poet, mathematician, and astronomer. He is best known for the Rubáiyát, quatrains exploring love, fate, and doubt, and for reforming the Jalali calendar with remarkable precision.

Neil deGrasse Tyson

Neil deGrasse Tyson (b. 1958) is an American astrophysicist, author, and science communicator. As director of New York’s Hayden Planetarium, he is known for popularizing astronomy and making cosmic ideas accessible worldwide.

Jorge Luis Borges

Jorge Luis Borges (1899–1986) was an Argentine poet, essayist, and short story writer. His works, such as Ficciones, explored infinity, time, and paradox, making him one of the most influential literary voices of the 20th century.

Leave a Reply