|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

What if Dolores Cannon debated Bart Ehrman on reincarnation in the Bible?

Introduction by Dolores Cannon

Reincarnation in the Bible is one of those questions people shut down too quickly, not because the evidence is settled, but because the story they inherited feels safer when it stays simple. In this imaginary conversation, I’m not trying to “win” against Christianity. I’m trying to separate three things that get mixed up: what the Bible explicitly teaches, what early Christians chose to emphasize, and what human consciousness may actually do.

Because when someone says, “The Bible doesn’t teach reincarnation,” that’s a statement about doctrine and interpretation, not a courtroom verdict on reality. Even Christian sources arguing against reincarnation often rely on the idea that Scripture points to one life and judgment, not repeated earthly returns. Yet the same debate keeps resurfacing around the same pressure points: Elijah and John the Baptist, people mistaking Jesus for “Elijah” or another prophet, and later battles over what kinds of soul-theories were allowed to be discussed in public Christianity.

So we’ll do this in a way that respects history and still tests the big claim. If resurrection became the master storyline early, then “no reincarnation” may have grown less from proof and more from a tradition that protected its center. And if reincarnation is real, it doesn’t need a verse to exist. It needs fair standards of evidence and honest questions.

(Note: This is an imaginary conversation, a creative exploration of an idea, and not a real speech or event.)

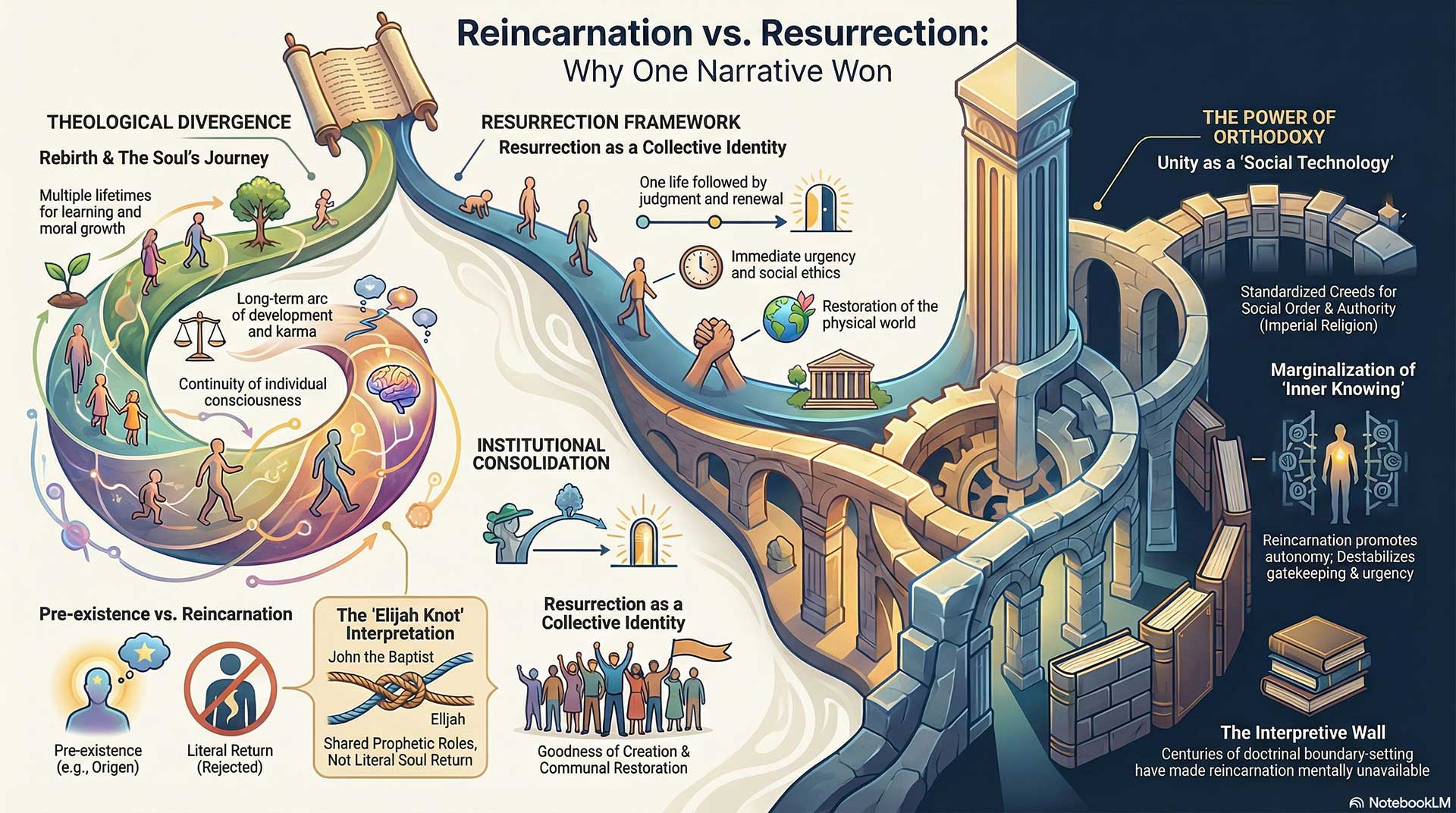

Topic 1: Resurrection vs Rebirth

Karen Armstrong: Let’s begin with the simplest friction point. Early Christianity came into the world with a very specific promise on its tongue: resurrection. Not a recycling of lives, but a transformation of the whole person. So here is what I want to ask, plainly, without jargon. Did Christianity define itself so early and so strongly around “one life, then resurrection” that reincarnation became almost impossible to hear, even if someone thought they saw hints of it?

N. T. Wright: Yes, and I would add that it wasn’t merely a preference. It was identity. The earliest Christian proclamation is not “your soul is immortal and returns.” It is “God has raised Jesus from the dead,” and that act is the start of a new creation. In that framework, the human story is not a ladder of successive attempts. It is one life lived inside a larger covenant story, then death, then God’s act of new life. If you place reincarnation in the center, you change the entire shape of the hope and the meaning of justice. Early Christians were arguing against both pagan ideas of disembodied immortality and certain philosophies of the soul. They insisted on bodily resurrection, which immediately pushes against a system of repeated embodiments.

Elaine Pagels: I agree that resurrection was central, but I want to widen the lens. Early Christianity was not a single choir singing in unison. It was more like a city of small houses with lights on in different windows. Some groups were intensely apocalyptic, some more mystical, some philosophical. You can find language about being “born again,” about putting on a new self, about the soul’s transformation. The question is what the dominant leadership later chose to protect and standardize. Once the movement is shaping a communal identity, it tends to favor a coherent public message. Resurrection is communal and historical. It binds people into a shared story. Reincarnation, even if someone privately believed it, tends to individualize the spiritual journey and can pull attention away from the urgency of social ethics and communal belonging. So yes, it becomes hard to hear, but not necessarily because nobody ever wondered. It’s because the public narrative needed clarity.

Bart D. Ehrman: From a historical standpoint, the earliest sources we have, especially Paul, emphasize resurrection, not reincarnation. The language is quite specific. The dead will be raised. There will be judgment. The world will be set right. That is a different concept from the soul returning to live another earthly life. It’s not that the early Christians are sitting in a room and choosing to ban reincarnation to gain power. It’s that their texts and their preaching are built around a particular apocalyptic expectation. When later interpreters read those texts, the default meaning is already set by those early commitments. Could individuals have speculated about the soul? Sure. But the mainstream message we can reconstruct is not reincarnation-friendly.

Jim B. Tucker: I come at this from a different direction, because I’m not primarily trying to win a theological argument. I’m looking at the question: if some form of reincarnation happens, would an early religious movement necessarily encode it clearly? Not always. Movements often emphasize what they need for cohesion and moral urgency. So I can accept what’s being said about resurrection as the early Christian center, and still say it does not logically exclude reincarnation as a phenomenon. It may simply mean the tradition chose a framework that was easier to teach, unify, and defend. In my world, evidence is not a verse. It’s cases, patterns, and explanations that fit the data with the fewest distortions.

Dolores Cannon: Exactly. I’m not here to pick a fight with Christianity. I’m here to say: show me the evidence against reincarnation. People say, “It’s not in the Bible,” as if that settles reality. But reality does not negotiate with committees. In my work, people report consistent patterns, not random fantasies. They describe continuity of consciousness. They describe lessons, themes, even what they call planning. So when someone says Christianity “could not hear” reincarnation, I hear a human story: a movement needed one simple message for salvation, and anything that suggested many lifetimes sounded like it weakened urgency or threatened authority. The absence of a doctrine is not proof of nonexistence. It’s proof that a doctrine was not preferred.

Karen Armstrong: Then let me sharpen it. If resurrection becomes the master story, what happens to the passages, images, and phrases that could suggest something like return, like continuation, like multiple chances? Do they get reinterpreted by default?

Jim B. Tucker: In psychology we see this constantly. A person with a strong expectation will reinterpret ambiguous information to fit the expectation. That’s not an insult. It’s how human cognition works. If your framework is “one life,” then anything that smells like “return” becomes metaphor or role. If your framework is “many lives,” then the same lines become literal hints. So the key is to identify which texts are truly unambiguous. In the Bible, many of the passages people cite are not unambiguous. That’s why the argument never ends. But again, ambiguity does not rule out the phenomenon. It only shows the text was not written as a manual for it.

Elaine Pagels: And the social process matters. Once a community builds boundaries, it develops interpretive reflexes. You can watch it happen in real time in any movement. There is a need for teachers to say, “This is what we mean,” and “This is what we do not mean.” Even if a text could be read in multiple ways, the community selects one reading and trains people to find it “obvious.” Over time, it feels like common sense. The interesting question for your project is not just whether reincarnation exists, but how the feeling of obviousness gets constructed.

N. T. Wright: But I want to resist the implication that this is merely psychological conditioning or institutional convenience. The resurrection hope is not chosen because it is easier. It is chosen because it is what the earliest Christians believed happened to Jesus. Their claim is not about the soul escaping. It is about God’s faithfulness to creation. If you import reincarnation, you alter the narrative of the body, the goodness of creation, and the meaning of redemption. Early Christians were saying, “This world matters and will be renewed.” They are not saying, “You will keep coming back until you get it right.” That is a fundamentally different moral universe.

Bart D. Ehrman: And historically, we need to be careful with “they reinterpreted it” as if it were a conspiracy. Many interpretations are simply inherited. If the earliest texts are not teaching reincarnation explicitly, later interpreters do not have to twist them to avoid reincarnation. They just read them as they appear in their own worldview. The Elijah and John the Baptist discussion is the classic example. People see it and think, “Aha, reincarnation.” But the text itself provides a harmonization through language like “spirit and power,” and within Jewish prophetic tradition, the return of Elijah is often understood as the return of a role, a prophetic function, an eschatological sign. That interpretive option was already available.

Dolores Cannon: But notice what’s being admitted, even gently. You can harmonize it away. That’s the point. If it can be harmonized away, it can also be harmonized toward. The question becomes: what did people need to protect? If you tell people they have one life and eternal stakes, they are easier to direct. If you tell them they have many lifetimes to learn, they might become less fear-based and more growth-based. That does not make them immoral. It may make them more responsible, because karma is not just punishment. It’s learning. So I’m not saying anyone is evil. I’m saying there are incentives.

Karen Armstrong: Let me ask the third question in a way that forces all of you onto the same playing field. If reincarnation were true, what would we expect the New Testament to sound like? What would it emphasize, and what would it avoid?

N. T. Wright: If reincarnation were central, we would expect repeated, clear, didactic teaching. We would expect ethical arguments grounded in it, the way Paul grounds ethics in resurrection. We would expect community practice shaped by it. Instead we see baptism as participation in Christ’s death and resurrection, one decisive turning, not one episode in a long series. We see warnings about judgment and hope for renewal. It’s not that reincarnation could not exist as a metaphysical possibility, but the New Testament does not present it as the framework.

Elaine Pagels: If reincarnation were a mainstream teaching, I would expect more explicit language about the soul’s repeated embodiment, especially in communities influenced by Greek thought where such concepts were already circulating. Yet the texts that became canonical lean toward a Jewish apocalyptic horizon and a decisive end. However, I would also expect diversity at the margins. And we do see diversity in early Christian thought about the soul, angels, heavens, cosmic layers, and mystical ascent. So the absence of explicit reincarnation language in the canon does not settle what every early Christian imagined. It settles what became the public, authorized center.

Bart D. Ehrman: From the standpoint of historical-critical reading, if reincarnation were taught by Jesus or the earliest communities, we would expect it to show up more plainly and more often, and in multiple independent traditions. Instead, the material that gets cited is typically ambiguous, isolated, or dependent on interpretive leaps. That doesn’t disprove reincarnation as a phenomenon in the universe. It does suggest it was not the standard Christian doctrine, and it makes the claim “early Christians suppressed the truth of reincarnation” harder to establish historically.

Jim B. Tucker: If reincarnation were true, I would not necessarily expect an ancient religious text to describe it like a textbook. I would expect human beings to bump into it. I would expect stories of children remembering, people feeling continuity, strong impressions that do not fit a single-life narrative. Then the culture decides what to do with it. Some cultures build it into their worldview. Others interpret it as spirits, demons, visions, symbolism, or heresy. So if reincarnation exists, the New Testament might still sound exactly like it does: focused on moral urgency, social community, and a big cosmic promise. The text might be describing the way people should live, not the full mechanics of consciousness.

Dolores Cannon: If reincarnation were true, I would expect exactly what we see in real life: fragments. Hints. Paradoxes. Stories that do not fully align if you force them into one rigid framework. Human beings are complicated, and spiritual reality is not obligated to be neat. I would expect institutions to simplify. I would expect believers to defend what gives them certainty. And I would expect a small number of seekers to say, “Wait, that line sounds like return. That story sounds like continuity.” Then they get told, “No, no, you’re reading it wrong.” My claim is simple: you can say the New Testament doesn’t teach reincarnation explicitly. Fine. But you cannot honestly say that proves reincarnation does not exist. It proves only that the tradition chose another centerpiece.

Karen Armstrong: That’s a strong place to pause. We have something like a shared ground, surprisingly. Resurrection is clearly the public center of early Christianity. Yet that does not logically settle the metaphysical question of reincarnation. The real battleground is how communities create a master story that makes certain interpretations feel natural and others feel impossible.

Topic 2: The Elijah Problem

Karen Armstrong: Let’s step onto the most contested patch of ground. The New Testament gives us a knot of statements that people keep returning to because it sounds like identity crossing lifetimes. Jesus speaks as if John the Baptist and Elijah are connected, yet John denies being Elijah, and another text speaks of coming in the spirit and power of Elijah. So here is what I want to know. When Jesus links John and Elijah, are we looking at literal identity, symbolic fulfillment, prophetic role, or something that could honestly be described as a return?

Dolores Cannon: When I hear that kind of knot, I don’t hear contradiction. I hear layers. The simplest explanation to me is that there is continuity that the mind tries to explain in a limited vocabulary. People want one clean label. “Reincarnation” or “not reincarnation.” But spiritual reality might not care about our neat boxes. If a soul can carry a mission thread across lives, then you can see why Jesus would speak in a way that points to continuity, and John could still deny a literal identity the way people imagine it. Because he is not walking around thinking, I am Elijah in a simple sense. He is himself, with a deeper current flowing through him.

Bart D. Ehrman: Historically, the expectation of Elijah’s return is a Jewish end-times theme. It shows up outside the New Testament as well. So when Jesus talks about Elijah and John, one immediate interpretive frame is not Greek reincarnation, but Jewish eschatology. In that world, Elijah’s “return” can mean the return of the prophetic function. John is the Elijah-like forerunner. The tension you mentioned is real, though, because the texts do not line up neatly if you read them like a police report. But ancient texts often preserve multiple traditions, and later authors try to harmonize them. That is not always sinister. It is normal.

Elaine Pagels: I want to slow down and notice something. People often assume the only options are literal reincarnation or total metaphor. But there’s a third space in many spiritual traditions, including Jewish prophetic imagination. A person can embody a role. A life can be seen as the unfolding of a pattern. That can feel like “return” without being a repeated identity in the strictest sense. The community then chooses how to teach it. If your community fears anything that sounds like multiple lives, you steer the interpretation toward role and symbolism. If your community expects souls to travel, you steer it toward literal return. The same texts become a mirror of what the community is prepared to accept.

N. T. Wright: There is also the basic reading that the New Testament itself hands you. It does not say John is Elijah in the sense that Elijah’s soul returned into a newborn body. It says John fulfills the Elijah expectation as the prophet who prepares the way. And when Luke uses the phrase about “spirit and power,” that signals vocation and empowerment, not identity transfer. You can call that an interpretive choice, but it is more than a convenient dodge. It fits the Jewish storyline and the Christian claim about God’s action in history moving toward a decisive renewal.

Jim B. Tucker: I hear two things happening. One is textual interpretation. The other is what people psychologically do with ambiguous material. If someone is motivated to find reincarnation in the Bible, this is where they will camp. If someone is motivated to protect a one-life framework, they will camp here too and build guardrails. What makes this a useful topic is that it shows the mechanism of interpretation in motion. It also raises a question I care about: does the text intend to describe the mechanics of consciousness, or is it describing a meaning. If it is the latter, then it may never settle the metaphysical question either way.

Karen Armstrong: Let’s press into the harmonization that tends to end the argument in many churches. Luke’s phrasing about John coming in the spirit and power of Elijah is often used as the safe bridge. Why did that reading become the default. What does it protect. What does it allow people to keep believing without panic?

N. T. Wright: It protects the coherence of the story. Christianity is not built around the soul migrating from body to body. It is built around the one God who will put the world right. That includes the body. If you make identity a wandering spark that repeatedly occupies bodies, you weaken the Christian insistence that this body and this creation matter and will be redeemed. The “spirit and power” reading allows the tradition to say, yes, prophecy can echo, roles can reappear, history can rhyme, without changing the core promise.

Elaine Pagels: It also protects authority in a softer sense. Not necessarily control by fear, but control by clarity. A community survives by being able to teach ordinary people what to expect. Multiple lives creates questions. Why suffering. Why inequality. What about salvation. What about urgency. If you keep the framework as one life and a decisive horizon, you can preach repentance, justice, and hope with a clean edge. The “spirit and power” language allows you to keep the poetry and power of Elijah imagery without opening a door you do not want to manage.

Bart D. Ehrman: And from the perspective of early Christian diversity, it is the least anachronistic move. Reincarnation is not the default Jewish category for Elijah’s return. So the “spirit and power” reading is not simply a later church invention. It is a plausible ancient explanation. Now, people will argue about which texts came first and how traditions developed, but the point remains: the mainstream reading has ancient roots. That makes it less like a later conspiracy and more like a continuity of interpretation.

Dolores Cannon: But notice the emotional truth underneath. People want safety. They want a map that tells them their suffering will be answered. If you introduce reincarnation, you introduce a longer learning arc. That can feel compassionate and expansive, but it can also feel threatening to anyone who needs the immediacy of certainty. So the “spirit and power” interpretation becomes a spiritual compromise. It says, something is going on, a continuity is there, but we will not name it in a way that destabilizes our system. My problem is when that compromise gets sold as proof that reincarnation is impossible.

Jim B. Tucker: I think that’s an important distinction. You can say, this is the best interpretation within this tradition. You cannot leap from that to saying reincarnation cannot be real. The interpretive choice may be about preserving the tradition’s internal logic. That is fine. But it is not a scientific disproof. If the goal of your conversation is to make the case that the “no reincarnation” stance was developed early as an interpretive tradition, this is a great example. It shows how a community chooses the reading that creates the least disruption.

Karen Armstrong: Now the hardest question. Many people who argue for reincarnation say, if the Bible contains even one strong hint, it means the door is open. Others say, the Elijah material is the strongest supposed hint and it still does not cross the line into literal rebirth. So I want each of you to answer this without hedging. If you had to pick one, is this the strongest biblical hint toward reincarnation, or is it a category mistake where modern readers import a concept that the text is not actually using?

Bart D. Ehrman: Category mistake. It’s not the right conceptual box for the ancient context.

N. T. Wright: Category mistake. The text is doing prophetic fulfillment, not teaching rebirth.

Elaine Pagels: It’s a useful pressure point but not a smoking gun. It reveals interpretive power more than it proves reincarnation.

Jim B. Tucker: It’s not proof. It’s ambiguity. It can motivate curiosity, but it cannot settle the phenomenon.

Dolores Cannon: It’s a hint. Not a courtroom exhibit, but a hint. And I would say the very fact that it can be argued both ways tells you the door was never as locked as people pretend.

Karen Armstrong: Good. That lands exactly where we need it. Topic 2 shows how a tradition can be both sincere and selective. A reading can be ancient, not invented, and still function as a boundary that keeps certain possibilities unnamed.

Topic 3: Origen, the Soul’s Journey, and the Line That Got Drawn

Karen Armstrong: Now we leave the battlefield of hints and step into the room where ideas get classified. Here is the tension. Early Christian thinkers were not all the same. Some were mystical, some philosophical, some fiercely apocalyptic. And then, over time, certain ideas about the soul became not merely unpopular, but dangerous. So let me begin simply. What did early thinkers actually teach about the soul before birth, and how is that different from reincarnation?

Bart D. Ehrman: The first distinction is critical. Pre-existence of the soul means the soul exists before you are born. Reincarnation means the soul returns multiple times into multiple lives. People often collapse those into the same thing, but historically they are not identical. When you look at the writings associated with Origen and later debates around him, you find complex speculation about the soul, about God’s justice, about the purpose of embodied life. But it is a mistake to say, therefore early Christianity taught reincarnation and it was later removed. The better historical claim is that some Christians explored models of the soul that made later authorities uncomfortable, and those models were pushed to the margins.

Elaine Pagels: Right. What matters here is not only what a thinker like Origen wrote, but what later communities feared he implied. Origen represents a kind of Christian intellectual ambition, an attempt to make the faith speak to philosophical questions of his time. Once Christianity becomes more institutionally organized, the tolerance for speculative systems tends to shrink. Not because every leader is power-hungry, but because communities are fragile. Boundaries prevent fragmentation. The soul’s pre-existence is one of those ideas that can spiral into a whole cosmos of implications. It changes how you interpret sin, justice, grace, and the meaning of Christ. It is not surprising that later authorities wanted to draw a line.

N. T. Wright: And from the theological angle, the concern is not arbitrary. Christianity is anchored in the goodness of creation and the goodness of embodied life. If you begin teaching that souls existed before and are embodied as part of a cosmic fall or a necessary cycle, you risk smuggling in a view that the body is a punishment or an accident. That runs against the Bible’s creation narrative and against the resurrection hope. So even if some early Christians speculated, the mainstream tradition is likely to reject those ideas not merely out of control, but out of consistency with its central claims.

Jim B. Tucker: I want to separate two debates that keep getting tangled. One is, what did early Christians teach as doctrine. The other is, what might be true about consciousness. Those are different questions. You can have a tradition that becomes firmly one-life oriented and still have reincarnation happen as a phenomenon that the tradition explains away or does not emphasize. Historically, suppression and reinterpretation happen in every culture. Scientifically, you look at patterns, not councils. But for your story, the historical question is still crucial. When ideas become labeled as forbidden, people often stop exploring them openly, even if they privately suspect there is something there.

Dolores Cannon: And that is exactly why this topic matters. I do not need to prove that Origen taught reincarnation in a neat, modern way. What I need to show is the human process. There were seekers. There were thinkers. There were experiences people could not easily explain. And then there were leaders who needed the faith to be stable, teachable, and uniform. So they did what institutions always do. They narrowed the field. They made certain ideas sound dangerous. And after enough generations, people forget there was ever another way to think.

Karen Armstrong: Let me ask the second question, because it forces motive into the open. When later Christian authorities condemned certain soul-speculations, what problem were they trying to solve. Was it truth. Unity. Control. Or confusion.

Bart D. Ehrman: Historically, the answer is usually a blend. Leaders believed they were protecting truth. They were also protecting unity. And yes, unity produces control, whether intended or not, because once you define the boundaries, you define who is inside. But I would be cautious about turning this into a simple drama of villains and victims. In the ancient world, rival teachings could fracture communities quickly. The pressure to standardize was intense.

Elaine Pagels: I would add that confusion is not trivial. If you tell people the soul existed before birth, then you have to explain why the soul is here, what it did before, why some people suffer more, whether salvation is a recovery of memory, whether Christ is necessary, whether history matters. Those are not small side questions. The more speculative the system, the more it competes with the central public message. So leaders may have sincerely thought, we are preventing confusion. But the outcome is the same. A boundary is drawn, and certain possibilities become almost unspeakable.

N. T. Wright: Also, Christianity is not merely a philosophy of the soul. It is a story about God and the world. Once you shift it toward a system where souls are on a long loop of self-improvement, you can unintentionally demote the public claims about God’s action in history. Leaders likely felt, we must keep the focus on Christ, on the cross and resurrection, on the coming renewal of creation. That does not require malice. It requires a clear center.

Jim B. Tucker: Yet from the outside, it does look like a narrowing of permitted inquiry. When a community prohibits certain questions, even for sincere reasons, it can create blind spots. In medicine, in science, in psychology, and in religion, taboo can freeze exploration. If reincarnation is real, taboo does not erase it. It just reroutes how people explain their experiences. They call it possession, visions, imagination, or they stay quiet.

Dolores Cannon: And when people stay quiet long enough, a whole culture loses a vocabulary. Then the next generation looks at the same human experiences and has no way to interpret them except through the approved categories. So the question is not only what the leaders intended. The question is what they produced. They produced a world where reincarnation was not just rejected, it was made mentally unavailable.

Karen Armstrong: That leads perfectly into the third question, the one that matters for your thesis. Did later doctrinal boundary-setting accidentally make reincarnation unthinkable, even for people who felt the text left room.

Elaine Pagels: Yes. That is how boundaries work. Once a belief is branded as heretical, even discussing it can feel like disloyalty. Over time, interpretation becomes reflex. People do not say, we interpret this passage to avoid reincarnation. They say, reincarnation is impossible, therefore that passage means something else. The conclusion becomes the premise.

Bart D. Ehrman: I can agree that boundary-setting shapes what is thinkable, while still saying that the earliest sources are not strongly reincarnation-friendly. Both can be true. The mainstream view may not have been invented to oppose reincarnation. It may have been original to the movement. But once that view is dominant, it becomes the filter that decides what is allowed to count as meaning.

N. T. Wright: I would phrase it differently. The tradition did not accidentally make reincarnation unthinkable. It intentionally emphasized resurrection because resurrection is the hope it proclaimed. If someone wants reincarnation, they are asking Christianity to become a different religion. Now, I will concede that individuals can have experiences they interpret as past-life memories. That is a pastoral and human question. But it is not the same as saying Christianity suppressed a doctrine it once held.

Jim B. Tucker: And here is the useful bridge. Even if Wright is correct about doctrine, Dolores can still be correct about the phenomenon. The tradition may never have taught reincarnation centrally, but its boundary-setting could still have made it culturally taboo, which affects how people interpret their experiences. Your conversation can show that both sides are arguing about different levels. One side is arguing about what Christianity meant to teach. The other is arguing about what consciousness might actually do.

Dolores Cannon: That is the heart of it. I am not trying to turn Christianity into something else. I am saying, do not confuse doctrine with reality. Early Christians built a strong story around resurrection. Fine. Later leaders protected that story by discouraging competing soul-theories. Fine. But then people made a leap and turned a preference into a denial of possibility. They started saying, there is no reincarnation because we do not teach it. That is not evidence. That is a boundary pretending to be proof.

Karen Armstrong: And now we have a clearer shape. Topic 3 is not about a missing verse. It is about how a tradition becomes a lens, and how a lens can become a wall.

Topic 4: Empire, Authority, and Allowed Belief

Karen Armstrong: Now we move from interpretation to incentives. Once Christianity stops being only a persecuted movement and becomes woven into the fabric of state power, something shifts. Beliefs are no longer just private visions. They become public order. So let me ask the first question. When Christianity gained institutional and imperial power, how did the need for unity change the way interpretation worked?

Bart D. Ehrman: It changed everything. When a movement is small, diversity can coexist because there’s no central mechanism to enforce agreement. Once the movement becomes a public institution, theological disagreements become political problems. Unity becomes not only desirable but necessary. The church develops creeds, councils, and mechanisms of orthodoxy. That doesn’t mean every decision is cynical, but it does mean that “correct belief” becomes bound up with the stability of a massive social body. Interpretations that might have been tolerated in a small circle can suddenly feel like threats because they fracture consensus.

Elaine Pagels: And there is another shift, quieter but profound. In a small group, a mystical idea can be personal, exploratory, even poetic. In an institution, ambiguity is expensive. It produces competing teachers, competing moral frameworks, competing claims of authority. So orthodoxy becomes not just a statement of truth but a social technology. It creates a shared language and a shared boundary. You might say it protects the vulnerable from confusion. You might also say it protects leaders from rivalry. Both can be true at the same time.

N. T. Wright: I want to add that unity is not merely control. It can be pastoral. A fractured church can become chaotic and harmful. But it’s also true that once you define the faith around certain central claims, you have to defend them from frameworks that alter them. The resurrection hope is not a small detail. It shapes the entire ethics and the entire idea of what God is doing in history. So when the tradition becomes institutional, it will naturally reinforce readings that keep that central story intact.

Jim B. Tucker: This is where reincarnation becomes socially interesting. If a community teaches one life and a decisive judgment, it can create a strong moral urgency. If it teaches many lives and long learning arcs, it can create a different moral psychology. Neither is automatically better, but they produce different kinds of compliance, different kinds of hope, and different kinds of fear. Institutions tend to prefer frameworks that are teachable, uniform, and motivating. Whether that’s virtuous or manipulative depends on how it’s used.

Dolores Cannon: And this is why I keep saying people confuse doctrine with reality. An institution can choose a doctrine because it serves unity. But unity does not prove the doctrine is the whole truth. If reincarnation exists, it exists whether the institution likes it or not. So the question becomes: what beliefs were socially stabilizing and what beliefs were socially destabilizing. Reincarnation implies spiritual growth across time, which can reduce fear and reduce dependence on authority. That can be beautiful for people. But it’s inconvenient for systems that rely on a single moment of compliance.

Karen Armstrong: That brings me to the second question. How do institutions tend to treat beliefs that imply multiple lifetimes, multiple chances, and a slow unfolding of justice?

N. T. Wright: Institutions will worry that it weakens the urgency of repentance and the seriousness of moral choice. If people believe they have endless chances, they may delay transformation. Christianity’s proclamation has an edge to it: the time is short, the kingdom is at hand, now is the moment. That isn’t merely a control mechanism. It’s an ethical wake-up call. A multi-life model can soften that edge.

Elaine Pagels: Yet it can also deepen compassion. A long arc of moral development can lead people to see others not as damned enemies but as unfinished souls. The trouble is that it complicates categories. Institutions like clean categories: saved and unsaved, orthodox and heretical, inside and outside. Multiple lifetimes blurs those. It makes identity fluid, moral progress gradual, and it can make exclusion harder to justify. That is socially disruptive even when it is spiritually humane.

Bart D. Ehrman: Historically, we should remember that many ancient societies had beliefs in fate, spirits, afterlives, and cosmic cycles. The church was not rejecting reincarnation alone. It was negotiating its difference from many surrounding views. The more it defined itself as distinct, the more it needed clear lines. Multiple lifetimes can look like it collapses Christianity into a broader religious marketplace. If you’re trying to preserve identity, you draw away from it.

Jim B. Tucker: There’s also a practical issue. If people report experiences that sound like past-life memories, a culture needs a way to categorize them. In a reincarnation-affirming culture, those experiences become interpretable and sometimes guiding. In a reincarnation-denying culture, they become suspect or pathologized or spiritualized in other directions. Institutions often prefer categories they can manage: saintly visions, demonic deception, imagination, mental illness. Those categories keep authority intact because they keep interpretation in the hands of approved experts.

Dolores Cannon: And it creates fear around the very evidence that could broaden understanding. People have memories, impressions, knowledge they shouldn’t have. They’re told not to trust it. They’re told it’s dangerous. That’s not neutral. It shapes the whole civilization’s ability to explore consciousness honestly. If you want a single life framework, fine. But do not stamp out the vocabulary and then claim silence as proof.

Karen Armstrong: Now the third question, which makes it personal. If reincarnation encourages spiritual autonomy and long-term moral growth, would that have made it harder to govern a unified church and society?

Bart D. Ehrman: It likely would have. Beliefs that relocate authority inside the individual and distribute moral development across long time horizons can reduce institutional leverage. That doesn’t mean the institution is evil. It means institutions respond to incentives like any other human structure.

Elaine Pagels: I agree. Reincarnation can be a decentralizing idea. It says you are not dependent on one gatekeeper moment. It says your soul is learning in ways that may not fit the institution’s timeline. That’s why, in many traditions, ideas of inner knowing become contested. The institution wants to be the interpreter. The mystic wants direct experience. Reincarnation is not the only battleground, but it amplifies that struggle.

N. T. Wright: I would caution against reducing Christian doctrine to governance. The church’s goal was not primarily to govern but to proclaim what it believed God had done and would do. Still, yes, ideas have social consequences. If reincarnation shifts the center from God’s future renewal to the soul’s repeated self-development, it changes what the church is for. That will naturally create tension with the church’s self-understanding.

Jim B. Tucker: What I like about this topic is that it shows how a belief can be rejected for reasons that are not strictly evidential. A community can reject reincarnation because it destabilizes their moral narrative, their urgency, their authority structure, or their identity boundary. That doesn’t answer whether reincarnation exists. It answers why a society might prefer not to talk about it.

Dolores Cannon: And that’s my point. The rejection is often a social decision dressed up as a metaphysical certainty. The church can say, “This is not our teaching.” Fine. But people went further and said, “Therefore it cannot be true.” That’s the moment where a boundary becomes a blindfold. Reincarnation didn’t need to be refuted. It only needed to be made unthinkable.

Karen Armstrong: So Topic 4 gives us a crucial insight. Once belief becomes public order, the question shifts from “What is true?” to “What holds?” and those two questions do not always align.

Topic 5: Evidence vs Interpretation

Karen Armstrong: We have arrived at the decisive question. We have talked about the Bible as a text, the early church as a community, and empire as an incentive structure. But all of that still leaves a modern reader with a practical dilemma. If reincarnation exists, what counts as evidence. If reincarnation does not exist, what would disprove it. So here is my first question. What should count as “evidence” in this debate: manuscripts, history, lived experience, logic, or all of the above?

Jim B. Tucker: In a serious inquiry, it’s all of the above, but you have to keep categories separate. Manuscripts tell you what a text says and how it circulated. History tells you what communities believed and why. Logic tells you whether an argument is coherent. But none of those alone settles a question about consciousness. For that, you look at empirical patterns. In my field, the strongest kinds of cases are those with verifiable details, especially when very young children report information they plausibly did not learn through normal means. That doesn’t prove reincarnation with mathematical certainty, but it’s a kind of evidence that deserves sober attention rather than ridicule.

Bart D. Ehrman: And from my angle, the Bible is not an evidence file for reincarnation either way. It is a collection of ancient writings with particular theological aims. If someone uses it to prove reincarnation, they usually rely on ambiguous passages. If someone uses it to disprove reincarnation, they often mistake the absence of teaching for a denial of possibility. Historically, Christianity did not teach reincarnation as a mainstream doctrine. That is the most responsible claim the historian can make. The metaphysical question is a different matter.

N. T. Wright: I agree the Bible is not a laboratory report, but it does make truth claims. It offers a coherent vision of human life: one life, accountability, and hope of resurrection. If you ask what counts as evidence, in theology the evidence includes the coherence of the worldview, the moral fruits it produces, and the faithfulness to the texts and traditions. For Christians, resurrection is not merely one hypothesis among many. It is the heart of the proclamation. So even if reincarnation is intellectually imaginable, it does not fit the Christian narrative without fundamentally reshaping it.

Elaine Pagels: I would add that “evidence” is also social. Communities decide what they will treat as credible. A mystical experience may be treated as revelation in one community and delusion in another. So a fair-minded approach has to ask: who gets to define credibility. The early church increasingly centralized that power. Modern readers inherit the result: many people treat certain experiences as impossible because their tradition trained them to do so. That is not evidence against the experience. It is evidence about cultural framing.

Dolores Cannon: And this is where I’m very direct. People keep saying, “There is no evidence.” But what they really mean is, “There is no evidence I am willing to accept.” In thousands of sessions, people describe patterns: themes of learning, continuity of consciousness, relationships returning, and a sense of purpose that doesn’t fit the idea of one roll of the dice. You can debate methods, you can critique the process, but you cannot honestly say the only possible explanation is imagination. At minimum, it’s data. And when data exists, the responsible question is: what model best explains it.

Karen Armstrong: Second question. Is the mainstream rejection of reincarnation a conclusion from the text, or a tradition reinforced by centuries of interpretation?

Bart D. Ehrman: Mostly tradition, though grounded in the text’s dominant themes. The New Testament’s authors were not teaching reincarnation. That’s a textual and historical observation. But the leap from “not taught” to “impossible” is a tradition move. It’s not a historical argument.

Elaine Pagels: Tradition reinforced by interpretation, by authority, and by repetition. Once a belief becomes the identity marker of the group, it’s not simply an idea. It’s belonging. That makes it very hard to revisit.

N. T. Wright: It is both. The tradition believes it is faithful to the text and to the earliest proclamation. The problem is that many people caricature this as mere institutional control. But Christians argue that resurrection is what the apostles proclaimed. So the rejection of reincarnation is not merely a later invention. It is part of what the movement has been from the start.

Jim B. Tucker: Yet the key point remains. Even if Christianity rejects reincarnation doctrinally, that does not answer whether reincarnation occurs. It answers how the tradition frames human destiny.

Dolores Cannon: And I keep returning to the same hinge. Doctrine is not a microscope. Doctrine is a story a community agrees to live by. You can honor the story and still ask what else is true.

Karen Armstrong: Third question, and it’s the one that matters for a modern spiritual reader who wants to be honest. If reincarnation exists, what is the strongest fair-minded case that it can coexist with Christian faith without rewriting Christianity?

N. T. Wright: It is difficult, because Christianity’s hope is not the soul’s cycle but the resurrection of the body and the renewal of creation. If someone insists on reincarnation, they will have to radically reinterpret core doctrines. That is not a minor adjustment. It changes the shape of the faith.

Elaine Pagels: I see a possible bridge, though it will not satisfy strict doctrinal boundaries. Some Christians can hold reincarnation as a private metaphysical belief while remaining ethically and devotionally Christian. They might say: God’s mercy is larger than our maps. But institutionally, it will always be contested because it changes the grammar of salvation.

Bart D. Ehrman: Historically, you can find Christians who explored many ideas that didn’t become orthodox. But that doesn’t mean the faith “really taught” them. For coexistence, you’d need a model that doesn’t contradict resurrection language. Some might propose reincarnation up to a final resurrection. But that’s speculative and not grounded in mainstream texts.

Jim B. Tucker: From the outside, coexistence might look like this: Christianity describes the moral and relational purpose of life. Reincarnation, if real, describes the mechanism by which that purpose unfolds across time. One is meaning, one is process. People can hold both if they allow mystery. The risk is that each tradition worries the other will dilute its urgency.

Dolores Cannon: I would frame it as expansion, not dilution. Resurrection can be understood as a culmination, a transformation at a higher level, not necessarily a denial of multiple lifetimes. A person can live multiple chapters and still reach a final awakening. The issue is not God. The issue is human gatekeeping. If God is love, God is not threatened by reincarnation. Institutions are.

Karen Armstrong: Then here is the last thing I want to place on the table before we close. We began with your thesis that the “no reincarnation” view was developed early as a dominant interpretive tradition. We now see how that could happen without anyone falsifying a manuscript. A tradition can be sincere, text-rooted, and still become a wall that defines what is thinkable.

And we also see the unresolved truth. The Bible cannot function as a laboratory proof. It can shape meaning, identity, and moral urgency. The question of reincarnation is ultimately a question of how we treat human experience, how we define evidence, and whether we allow mystery without surrendering integrity.

Final Thoughts by Dolores Cannon

If you take nothing else from this, take this: doctrine is not the same thing as reality. The early church’s mainstream identity centered on resurrection, and many Christian interpreters argue the Bible gives no foundation for reincarnation. That tells you how the tradition framed the human story. It does not automatically tell you what consciousness can and cannot do.

What I wanted to show is how a “no reincarnation” worldview can become self-reinforcing. Ambiguous passages get harmonized toward the accepted framework. Elijah becomes “spirit and power,” not literal return. Soul-speculations like preexistence become dangerous to teach, and later summaries even include anathemas against ideas tied to Origen. Over time, people stop asking. And silence starts to look like proof.

But the honest posture is braver: hold the tradition respectfully, acknowledge what the text emphasizes, and still admit that the universe may be larger than our authorized vocabulary. That’s where real inquiry begins.

Short Bios:

Dolores Cannon – Hypnotherapist and author known for pioneering past-life regression research and exploring reincarnation, soul planning, and consciousness beyond time.

Karen Armstrong – Former nun and bestselling author whose work compares world religions with empathy, historical depth, and a focus on shared human meaning.

Bart D. Ehrman – Critical historian of early Christianity specializing in textual transmission, early belief diversity, and how doctrine developed over time.

Elaine Pagels – Scholar of early Christian texts and movements, widely known for illuminating marginalized and suppressed strands of early Christian thought.

N. T. Wright – Theologian and historian emphasizing resurrection, Jewish context, and the coherence of early Christian belief within its historical framework.

Jim B. Tucker – Psychiatrist and researcher known for studying children’s past-life memory cases using empirical and clinical methods.

Leave a Reply