|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Mary Oliver:

Henry David Thoreau lived as few dared to live—deliberately, inwardly, stubbornly true. He walked slowly. He noticed the trill of the sparrow, the stillness of ponds, and the brief bloom of wild roses. But what we rarely say—what we shy away from saying—is that solitude can ache. That silence can weigh like winter.

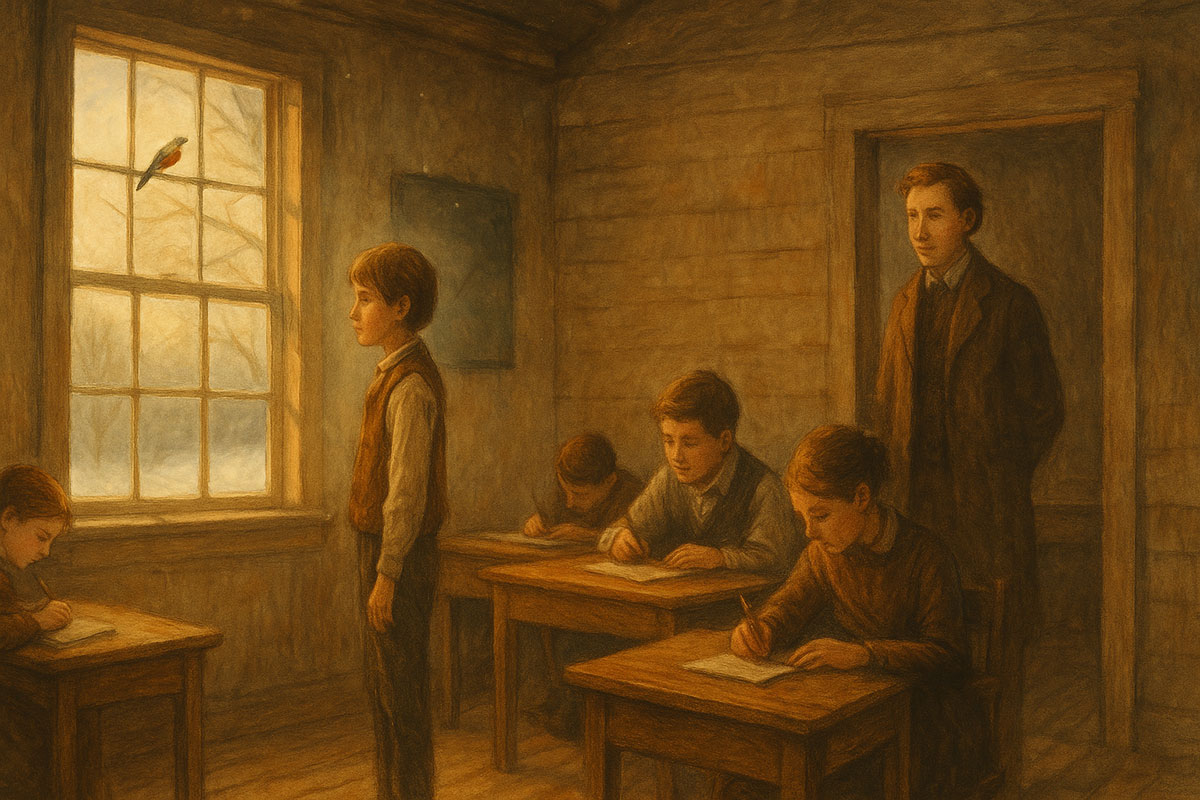

In these quiet chapters, we don’t return to Thoreau the philosopher or protester, but Thoreau the boy who once stood too still in a classroom. Thoreau the brother who buried grief beneath pine needles. Thoreau the man who both found freedom in the woods and longed for connection he could barely name.

What happens when we place a gentle hand over the hand of someone who rarely reached out? What comfort can we offer someone who believed that most men “lead lives of quiet desperation”?

These scenes do not aim to rescue Henry, nor rewrite him. They simply offer what he gave to the world—stillness, presence, and the chance to be seen.

(Note: This is an imaginary conversation, a creative exploration of an idea, and not a real speech or event.)

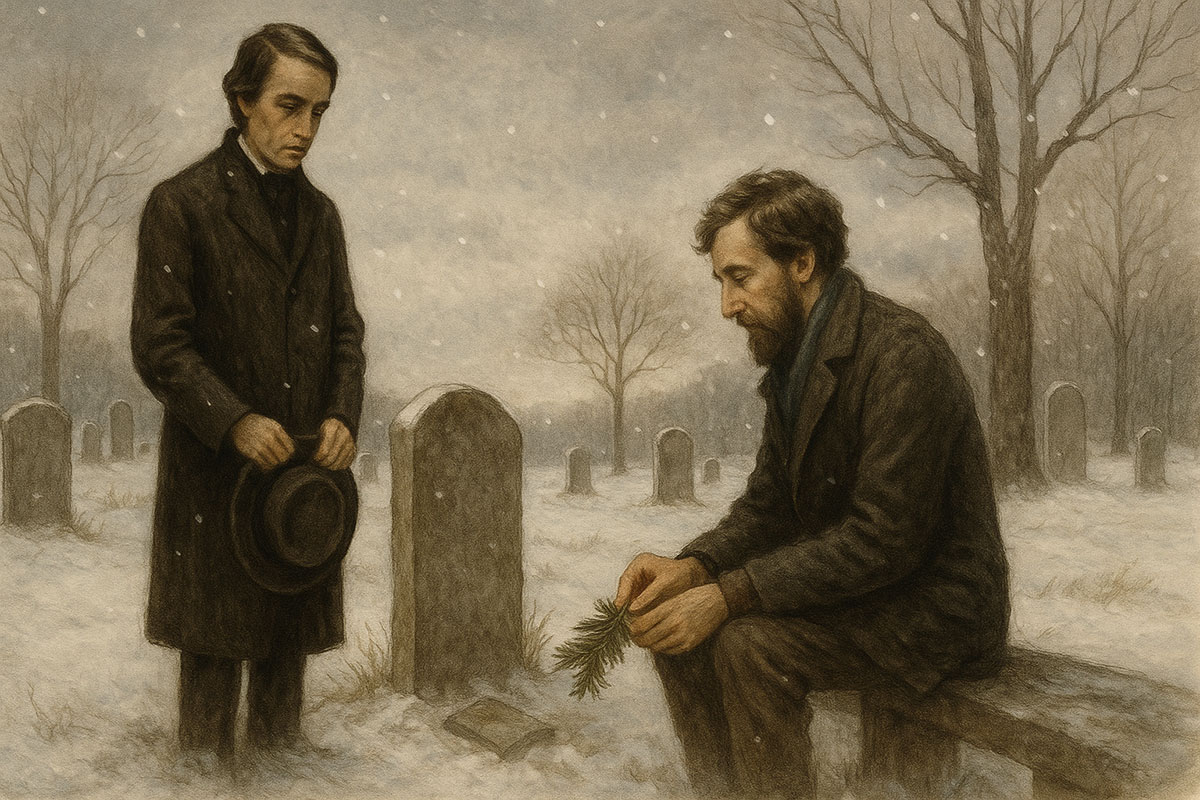

Chapter 1: The Death of His Brother

The river was quiet that day, quieter than usual, as if it too were in mourning.

Henry stood alone by the Concord, the wind gently combing through the reeds, his boots half-buried in the soft mud where he and John used to fish. The world had not changed—not the way the light filtered through the trees, not the call of the loons or the sighing hush of the leaves. But he had. Inside him, a stillness had rooted, hollow and hard.

John, the elder, the kinder, the more social of the two, had been his mirror in laughter and his shadow in grief. They had rowed together, taught school together, shared books and firelight and the fragile dreams of youth. And then suddenly—gone. A simple cut, an infection, a fever. The life bled out of him in days.

Now Henry kept walking the river path they once walked together, as if each footprint might call John back.

When I found him that morning, Henry was sitting on a flat rock with a notebook open, but the page was empty. His pencil dangled from his fingers like a thought too painful to touch.

“I should have died first,” he whispered.

I sat beside him, silent. The grief didn’t need words. It needed presence.

“You know,” he said after a long time, “we laughed just before he cut his finger. Something foolish. Something about frogs. I cannot remember it. But I remember the sound of him laughing. I wish I could have bottled that.”

He closed the notebook. Still no words. “I thought if I lived rightly, nature would protect those I loved.”

I looked out across the water. “Nature doesn’t promise safety, Henry. Only truth.”

He smiled bitterly. “I wanted to build a world where John still existed.”

“You did,” I said gently. “It’s in your walking. In every bird you pause to listen to. In every line of your journals.”

His eyes shone with unshed tears. “It hurts to breathe sometimes.”

“Then we’ll breathe together. Until it doesn’t.”

We stayed there for hours, watching the light shift. A heron lifted off in the distance, and the rhythm of the water began to speak again.

That night, he wrote only one sentence:

Grief is not the absence of life—but the proof of its depth.

Chapter 2: Isolation at Walden Pond

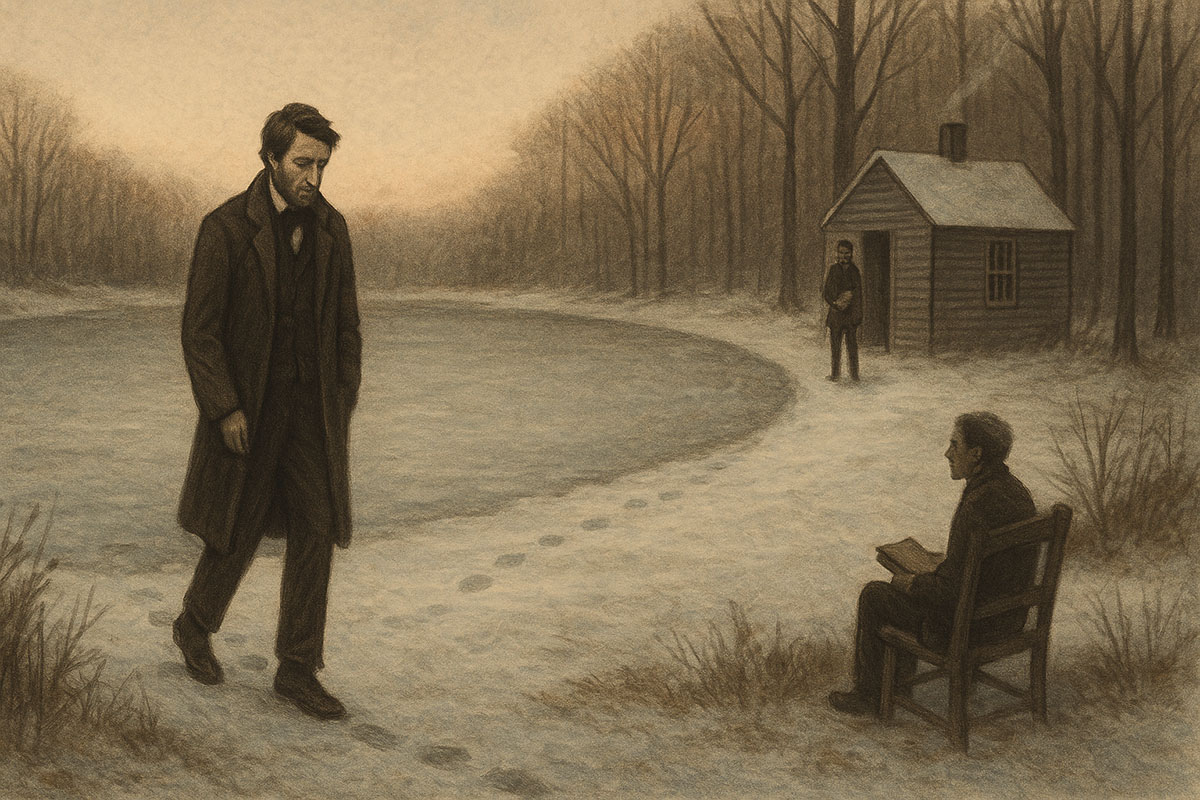

The pond held its breath.

Each morning, Henry stepped from his cabin, the door creaking like an old sigh. The air was cool, the trees motionless in their monastic stillness, and only the ripples answered his presence. He lived here not to escape the world, he often said, but to hear it more clearly.

And yet, some mornings, he felt the weight of being unseen.

I arrived on such a morning—just after a frost. The ground was silvered and crisp, his footprints the only ones between cabin and water. He sat on the edge of the small dock, wool coat wrapped tight, a tin cup of coffee cradled in his hands as if for warmth more spiritual than physical.

"Some days," he said without turning, "the stillness is a kind of ache."

I sat beside him, watching a lone leaf skate across the surface.

"They think I’m aloof," he continued. "That I live out here because I disdain people. But it’s not disdain. It’s… over-saturation. The world is loud with contradiction."

"And in the quiet?"

"Even louder," he admitted, softly. "Out here, I meet myself. And I don’t always like the company."

He handed me his journal. I flipped through sketches of pine needles, long passages on birdsong, and a single line repeated:

Am I living deliberately?

"I write it each day," he said. "Not to answer it—but to stay awake."

I nodded. “It’s a hard thing, to be fully awake.”

He smiled faintly. “Do you know the loneliest sound here? It’s not the owl, or the train whistle at night. It’s the echo of my own voice when I speak aloud to no one.”

And yet, in that moment, he was not alone.

“You’re not wrong to come here, Henry,” I said. “The world has its rhythm. So do you. This place lets you hear it.”

He closed his eyes. “Sometimes I feel the pond listens better than people.”

“It does,” I replied. “But people need what you’ve heard here.”

That night, I left him in candlelight, scribbling beneath a blanket, the window cracked just enough to let in the sound of wind through pine.

And in the morning, I found this written in the dirt outside the cabin:

Solitude is not the absence of company, but the deepening of communion.

Chapter 3: The Burden of Being Misunderstood

It was raining when I returned.

Not the loud kind, but that slow, steady drizzle that seeps into the wood, the ground, and the soul. The kind of rain that doesn’t ask permission. That simply arrives and lingers. Henry sat by the window, chin on palm, watching drops race each other down the glass.

"They say I hated society," he murmured without looking at me. “But I didn’t. I simply wanted it to mean something.”

I stepped inside and closed the door behind me. The fire had long since gone out, and the chill in the room was more than physical. On the small table lay a letter, unopened. The handwriting on the envelope was familiar—Emerson's. I noticed Henry hadn’t touched it.

“I’ve become a caricature,” he said bitterly. “They quote me to avoid listening. They paint me as some wild prophet in the woods, as if I slept on moss and spoke only to squirrels. But I paid taxes once. I bought nails. I felt hunger.”

“You still do,” I said gently.

He looked at me, eyes fierce but weary. “Have you ever screamed into a world that responds with applause instead of understanding?”

I nodded. “It hurts more than silence.”

Henry picked up the letter and held it like a stone. “Emerson means well. But even he doesn't quite see me anymore. I’m no sage. I’m a man with splinters under his fingernails, who sometimes wishes he could walk into town without someone whispering about Walden.”

We sat for a long while, listening to the rain thread itself through the trees. I noticed his boots by the door—worn through at the heel, patched with care.

“I wanted my life to be the message,” he whispered. “But all they saw was the metaphor.”

I stood and poured us tea. The steam curled like breath between us.

“There’s a difference,” I said, “between being admired and being understood. You were born for the second. But most people only know how to offer the first.”

He smiled, though it trembled. “Sometimes, I wish I could be ordinary. To wake up, chop wood, laugh with neighbors, go to sleep never having wrestled with the stars.”

“And yet,” I said, “if you were ordinary, the rest of us would never be reminded of what’s possible.”

The rain softened to a mist. Henry finally opened the letter. He didn’t read it aloud, but I saw the way his shoulders dropped, some unseen weight released.

Later that night, before leaving, I turned at the doorway. He was sitting by the fire now, journal in hand, scratching something into the margins.

Years later, I would find that page. It read:

They may not know me. But I lived so they could remember themselves.

Chapter 4: The Grief of a Dying Brother

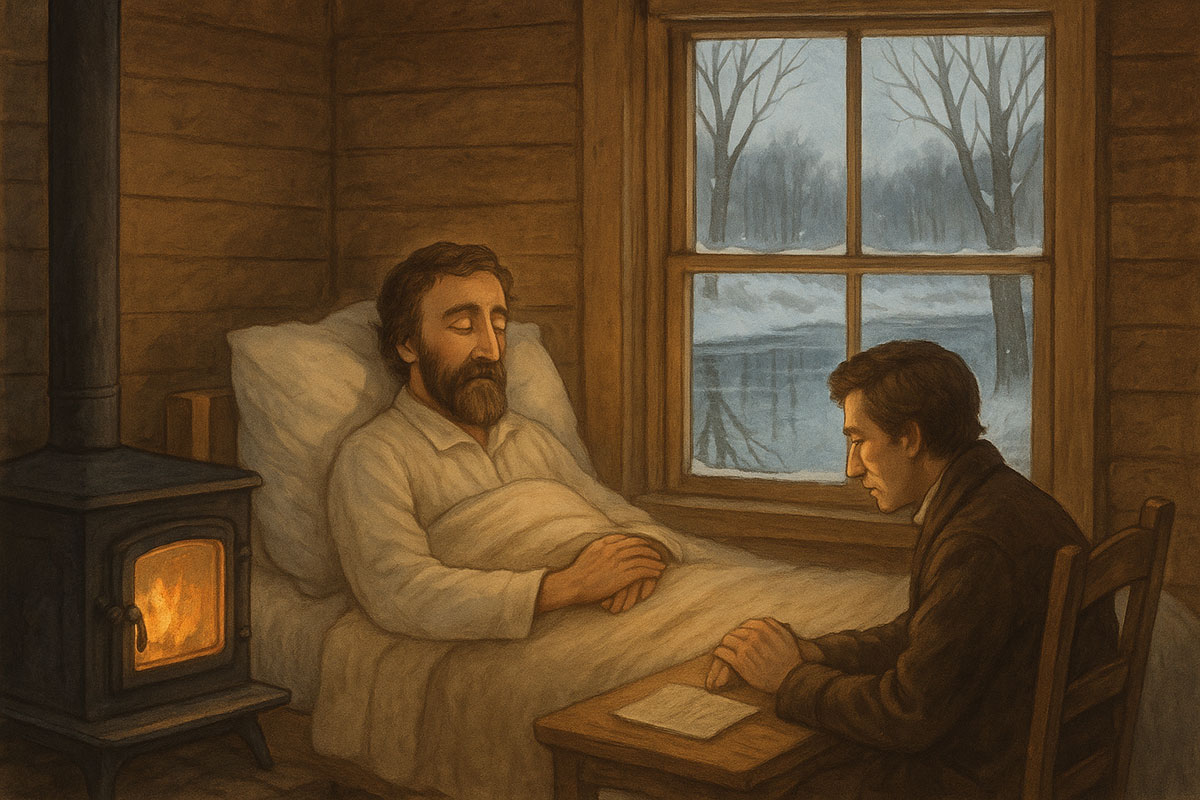

The room was filled with light, but it wasn’t kind.

It was the kind of light that exposes, that pulls no curtain over sorrow. A winter brightness, sharp and clinical, pouring through the frost-laced panes of Concord. On the bed lay John—Henry’s beloved older brother—his chest rising with effort, not rhythm.

Henry sat motionless beside him, both hands wrapped around John’s pale fingers, as if by holding tightly enough he could keep his brother anchored to the world.

“I used to think death was just another part of nature,” Henry whispered without turning. “But now that it wears my brother’s face, I want to rebel against it.”

I knelt beside him quietly.

“Do you remember the boat we built?” he asked. “It was clumsy, it leaked, but we spent that whole summer patching it with tar and laughter. John called it the ‘Musketaquid Dream.’”

His voice caught.

“We took it down the river together—no plan, no map. Just the current and our oars. He said if we died, we’d die free. And I believed him.”

John stirred, his lips parting. A word came out like wind through a keyhole: “Henry…”

Henry leaned closer, forehead to his brother’s.

“I’m here,” he said. “You don’t have to go anywhere alone.”

Outside, the trees stood sentinel, stripped bare by the season, like brothers shivering in shared silence.

“People think I came to Walden to escape,” Henry murmured, “but it was John who taught me how to be still. How to listen to frogs as though they were philosophers. How to wait for a heron and not rush the moment.”

He closed his eyes. “I don’t know how to live without him.”

I placed a hand on his back, gentle and firm. “Then don’t. Carry him with you—in the rhythm of your walking, in the words you write, in every breath that pauses to notice the world.”

John gave one final breath that lingered longer than it should have. Then silence.

It was the kind of silence that bends time.

Henry didn’t cry. Not then. He simply kissed his brother’s forehead and whispered, “You’ll be in every dawn.”

That night, we walked together through the woods, the snow softening our steps. The stars blinked above us, unworried and cold.

“I used to write about eternity,” Henry said, “but this is the first time I’ve tasted it. Not in some philosophical ideal—but in the unbearable permanence of his absence.”

I said nothing. Some truths are only safe in silence.

Later, in the margins of his journal, he would write:

Grief is the wilderness where love builds its second home.

Chapter 5: The Quiet Room at Walden’s End

The room was smaller than the world he had described, and yet it held the entirety of it.

A simple bed. A narrow desk. A cracked basin, half-filled with morning. A stack of notebooks, their bindings worn, edges smudged by callused thumbs. And outside the window—the pond, frozen solid, mirroring a sky that had forgotten its blue.

Henry lay with his hands folded over his chest. Breath thin as winter light. The cough had returned, rattling his bones like wind through dry reeds. But there was no fear in his face—only stillness, like a man who had walked long enough to reach the edge of sound.

I sat beside him, as always.

“You know,” he whispered, voice dry as an autumn leaf, “they keep asking if I’ve made peace with God.”

He smiled faintly.

“I didn’t know we were at odds.”

I smiled too. “You never were.”

“I think God is in the seed,” he continued, “in the ripple of the pond when no one’s looking, in the fox that stops just long enough to be seen. I think God was in John’s last breath… and in the silence after.”

A long pause. The fire in the stove gave a soft groan.

“I didn’t live greatly,” he murmured. “I didn’t build cathedrals. Didn’t marry. Didn’t sail the wide sea. But I did listen.”

He turned his head, slowly, deliberately, until his eyes met mine.

“Did I miss anything?”

“No,” I said, gently. “You caught what most spend lifetimes rushing past.”

A heron passed the window, dark against the pale sky.

He looked toward the pond. “It never really leaves you, does it? The wild. The stillness.”

“No,” I said. “It’s in you now.”

He looked up, the way a tree might look if it could lift its gaze to the sun.

“I’m not afraid to go,” he said. “Only sad to leave what I finally learned how to see.”

I reached over and placed a hand on his.

“Then don’t leave it. Let it walk with you.”

He smiled. “That sounds like something I would’ve said.”

“You did. Every day.”

He closed his eyes.

Outside, the pond shimmered beneath its crust of ice. Somewhere in the woods, a fox paused. Somewhere, snow began to fall—soft, slow, a quiet applause from the heavens.

Henry’s last breath was not dramatic. It was a sigh, like a page turning.

And in the silence that followed, I whispered:

“You lived deliberately. And the world, though it did not say so, was better for it.”

Final Thoughts by Mary Oliver

Henry David Thoreau biography, Thoreau final years, Thoreau Walden pond, Thoreau solitude, Thoreau emotional life, Thoreau death story, Henry David Thoreau reimagined, Thoreau last moments, Thoreau spiritual insight, Henry Thoreau peaceful death, Thoreau grief, Walden emotional journey, Thoreau intimate story, Thoreau poetic life, Thoreau final chapter, Henry David Thoreau last breath, Thoreau legacy reflection, Thoreau support series, Thoreau soul companion, Thoreau peaceful ending

Short Bios:

Henry David Thoreau

An American transcendentalist, writer, and philosopher (1817–1862), Thoreau is best known for Walden and his essay Civil Disobedience. He championed simple living, personal conscience, and a deep connection to nature.

Mary Oliver

A Pulitzer Prize–winning poet (1935–2019), Mary Oliver is celebrated for her accessible yet profound poems rooted in nature, solitude, and spiritual reflection. Her voice honors the sacred in the ordinary.

John Thoreau

Henry's older brother and closest companion, John died tragically young, leaving a lasting impact on Henry's emotional world. His death deeply shaped Thoreau’s view on loss and love.

Ralph Waldo Emerson

A fellow transcendentalist and mentor to Thoreau, Emerson provided both intellectual inspiration and material support, famously lending Thoreau land at Walden Pond for his experiment in simple living.

Sophia Thoreau

Henry’s younger sister, Sophia preserved his legacy after his death and was one of his most devoted supporters. An artist and naturalist herself, she understood and honored his inner world.

Leave a Reply