|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

What If T.S. Eliot Lived Next Door While Writing The Waste Land?

T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land is not a poem that tries to teach you something.

If anything, it does the opposite.

It places you in a world where explanations no longer work the way they used to.

For a long time, I approached Eliot the way most of us do — as a literary figure.

A major poet.

A historical voice.

Someone safely contained in books and footnotes.

But everything changed when I asked a different question:

What if T.S. Eliot lived next door to me?

Not as a genius.

Not as a monument of modernism.

Just as a quiet neighbor in postwar London, going to work each morning, carrying something heavy he never quite spoke about.

Suddenly, The Waste Land stopped feeling like an abstract poem.

It felt like a presence.

Like something written by someone who sensed — earlier than most — that the world had lost a shared center, and that pretending otherwise would be dishonest.

This imaginary conversation is not an attempt to explain Eliot.

It’s an attempt to sit beside him.

To listen to what remains when certainty disappears,

when meaning feels fractured,

and when silence begins to say more than language can.

(Note: This is an imaginary conversation, a creative exploration of an idea, and not a real speech or event.)

Scene 1 — The Neighbor in London

The story does not begin with greatness.

It begins in London, sometime around 1920.

A city still recovering from war, unsure how to move forward.

T.S. Eliot lived there then.

Not as a celebrated poet, but as a bank employee.

He wore proper clothes, kept regular hours, and spoke carefully.

If he had lived next door to you,

you probably would not have noticed anything remarkable.

He would have seemed quiet.

Serious.

Perhaps a little distant.

What made him different was not visible from the outside.

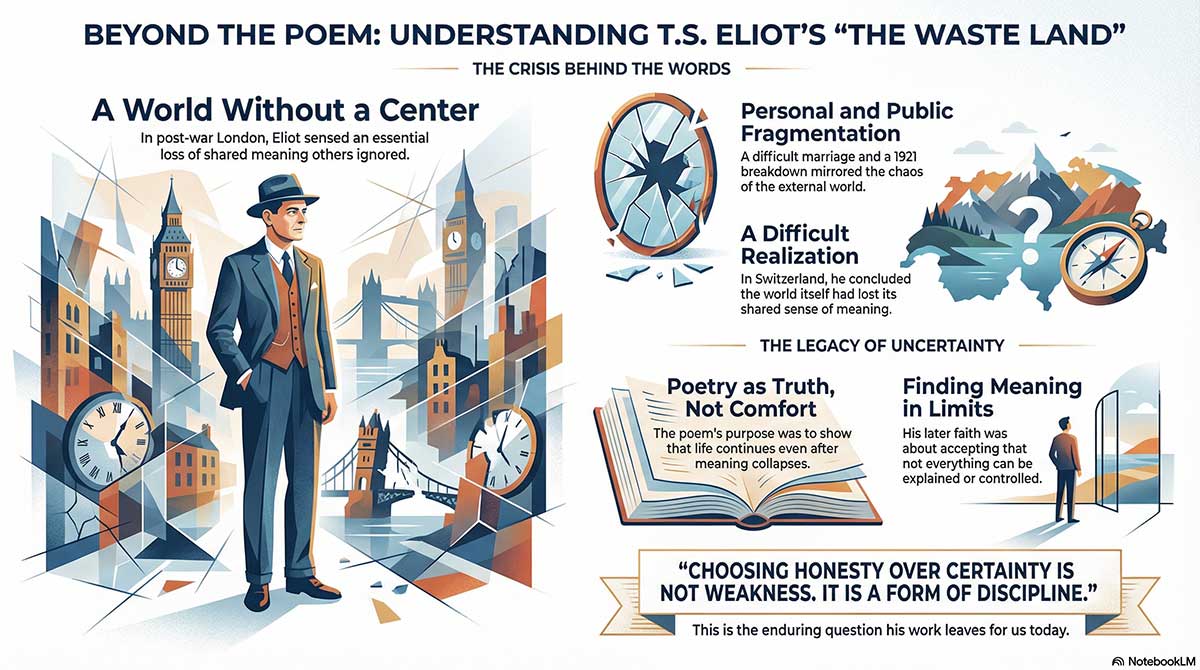

It was the way he sensed that the world had changed in a deeper way than people were willing to admit.

While others talked about rebuilding and progress,

Eliot felt that something essential had been lost —

and that it could not simply be repaired.

The Waste Land began as that awareness.

Scene 2 — Vivienne and the Unshared World

By the time Eliot was writing The Waste Land, he was already married.

His wife, Vivienne, lived with him in London.

She was expressive, emotional, and intensely alive to her surroundings.

They shared the same home,

but they did not share the same inner world.

Eliot retreated into silence.

He thought carefully before speaking.

He tried to manage pain by controlling language.

Vivienne, on the other hand, needed to speak.

Words were how she stayed connected to reality.

Later, many people described her simply as “ill.”

But that explanation misses something important.

She was living inside the emotional chaos that Eliot was trying to observe from a distance.

The women in The Waste Land are not portraits of Vivienne.

But the sense of disconnection —

of voices speaking without being heard —

runs throughout the poem.

Scene 3 — Switzerland at Night

In 1921, Eliot suffered a serious breakdown.

Doctors sent him to Switzerland to recover.

Away from London. Away from work. Away from his marriage.

At night, surrounded by mountains and silence,

he confronted questions he could no longer avoid.

Was his exhaustion a personal failure?

Or was it a symptom of something larger?

Slowly, he came to a difficult realization.

The problem was not only within him.

The world itself had lost its shared sense of meaning.

The Waste Land was not written to comfort readers.

It was written to tell the truth as Eliot saw it:

Life continues, even when meaning collapses.

That clarity did not bring peace.

But it brought honesty.

Scene 4 — Faith and Silence

A few years later, Eliot converted to Christianity.

This moment is often described as a turning point or a solution.

In reality, it was more complicated than that.

Eliot did not find easy answers.

He accepted limits.

For someone as intellectually disciplined as Eliot,

faith was not about belief alone.

It was about letting go of the need to explain everything.

Poetry still mattered to him.

But his poems became quieter, more restrained.

Silence, he discovered, could express what language could not.

This was not retreat.

It was a form of humility.

Scene 5 — The Question We Inherit

If Eliot were alive today,

he would probably not try to compete with modern noise.

He would not rush to offer opinions.

Instead, he would draw attention to moments

when language breaks down —

when words fail to match experience.

Eliot did not leave behind answers.

He left behind a way of standing in uncertainty without dishonesty.

These five scenes are not only about a poet in the past.

They quietly ask something of us now:

How do we live with uncertainty

without pretending it isn’t there?

Closing Note

This is an imaginary conversation.

But the questions it raises are real.

And they remain unresolved —

just as Eliot believed they should.

Final Thoughts by Nick Sasaki

Spending time with Eliot this way changes how you see him.

He was not a poet of despair.

And he was not offering solutions.

What he did, with unusual honesty, was recognize the limits of human understanding — and refuse to lie about them.

The Waste Land was written at the edge of that recognition.

It did not ask readers to feel hopeful.

It asked them to feel awake.

Later, Eliot moved toward faith and toward silence.

Not because he found easy answers, but because he accepted that some questions cannot be mastered — only lived with.

If Eliot were living among us now, I don’t think he would argue loudly or compete for attention.

I think he would remind us — quietly — that not everything meaningful can be explained, optimized, or resolved.

And that choosing honesty over certainty is not weakness.

It is a form of discipline.

This imaginary conversation ends here.

But the posture Eliot leaves us with does not.

It stays with us —

in how we listen,

in how we speak,

and in how we live with questions that refuse to disappear.

Short Bios:

T.S. Eliot

A major twentieth-century poet and critic, T.S. Eliot reshaped modern literature through works such as The Waste Land. His writing explored fragmentation, faith, silence, and the limits of language in a postwar world.

Vivienne Eliot

Vivienne Haigh-Wood Eliot was the first wife of T.S. Eliot. Often overlooked in literary history, her presence and emotional life formed part of the personal landscape surrounding the creation of The Waste Land.

Nick Sasaki

Nick Sasaki is the founder of ImaginaryTalks, a platform that explores timeless ideas through imagined conversations with historical and cultural figures, focusing on meaning, silence, and human understanding.

Leave a Reply