|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

What if top deterrence strategists and Russia experts debated whether “Russia will nuke UK and Germany” is bluff or doctrine—live, point by point?

Introduction by Nick Sasaki

Russia will nuke UK and Germany is the kind of headline that hijacks your body before your mind even catches up. Your chest tightens. Your imagination runs ahead. And suddenly you’re not evaluating information—you’re managing fear.

So here’s the deal: in this series, I’m not here to perform outrage, pick a team, or “win” an argument. I’m here to do something more boring—and more useful: separate signal from theater, separate capability from intent, and separate what’s scary from what’s likely.

Because when nuclear language enters the room, two mistakes become deadly:

- Dismiss it as bluff and sleepwalk into escalation.

- Treat it as inevitable and start making panicked moves that create the outcome you fear.

That’s why every topic in this roundtable is built for fairness. We’ll steelman both sides, call out propaganda wherever it shows up, and keep dragging the conversation back to the only question that matters: What reduces the risk of catastrophe—starting now?

If there’s one promise I can make you before we begin, it’s this: we are going to treat human lives as more important than narratives.

Let’s start.

(Note: This is an imaginary conversation, a creative exploration of an idea, and not a real speech or event.)

Topic 1 — The Nuclear Threat as Language: Deterrence or Blackmail?

A quiet studio with a roundtable lit like a late-night briefing room—soft lamps, water glasses, a map of Europe blurred on a screen behind them. No flags. No chest-thumping. Just the uneasy sense that words themselves have weight tonight.

Nick Sasaki:

Thanks for being here. The claim on the table is blunt: if this war drags on, Russia may escalate in ways Europe hasn’t truly metabolized—including nuclear threats naming specific countries. Whether that’s real intent or coercive theater… we’re going to treat it as a question, not a slogan.

Let’s begin with the first hard part: when a nuclear-armed state names targets, what are we hearing—deterrence, or blackmail?

The first question (asked naturally)

Nick Sasaki:

When Russia names specific countries in a nuclear context, is that deterrence—trying to prevent escalation—or blackmail—trying to force political submission?

Nina Tannenwald:

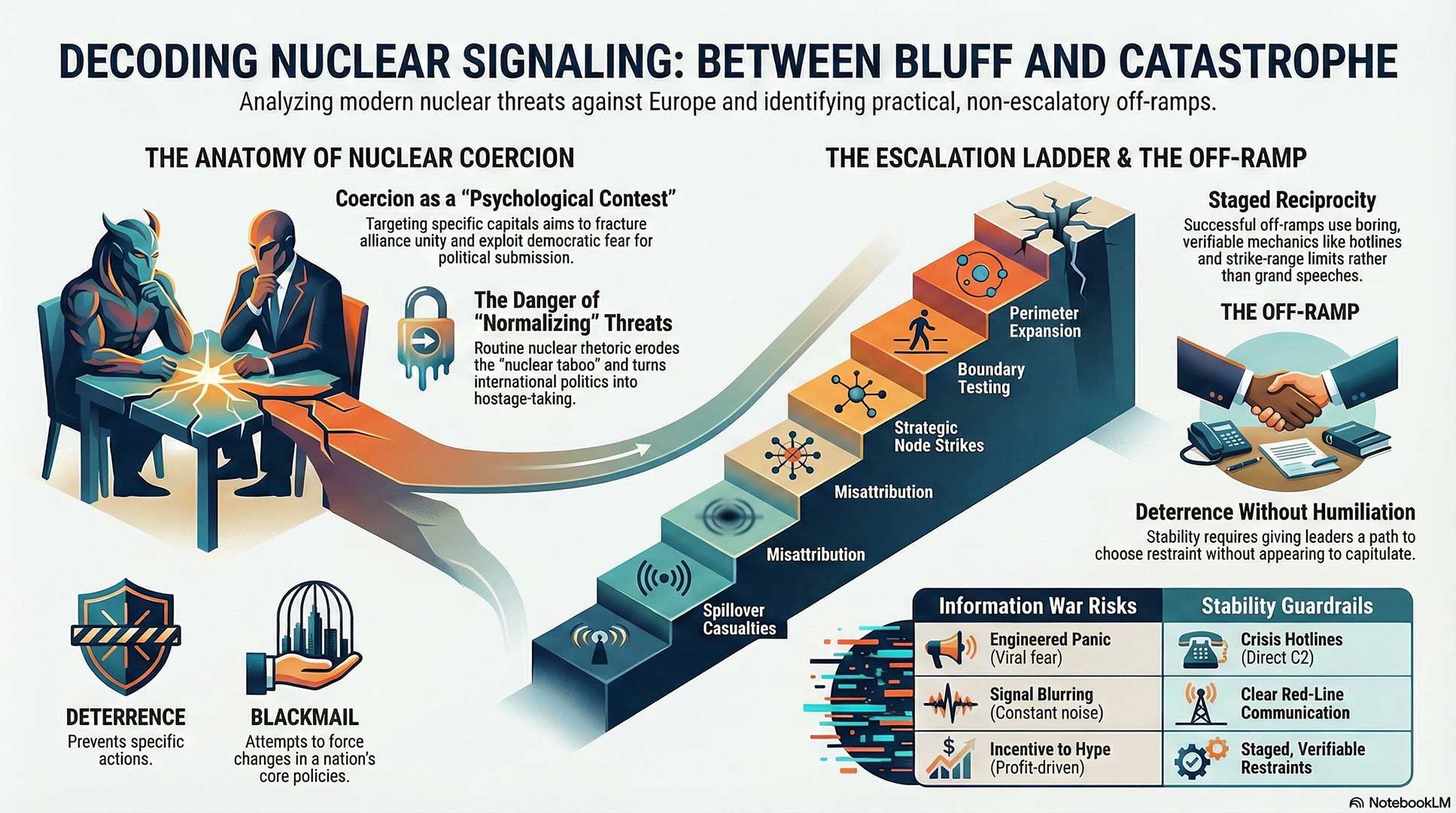

It can be both in form, but not in meaning. Deterrence is usually anchored to preventing a specific action: “don’t cross this line.” Blackmail is about bending another society’s political will: “change your policy, or I’ll harm you.” Naming specific countries shifts the psychological terrain. It targets public fear, alliance cohesion, and democratic fatigue. The danger is that normalizing nuclear talk corrodes restraint—the “nuclear taboo” depends on leaders and publics treating nuclear use as morally and politically extraordinary.

Kori Schake:

It’s coercion, full stop. The point is to fracture allied resolve—especially in democracies where fear can translate into elections, pressure, and policy changes. But here’s the trap: if you reward coercion, you teach every nuclear power that threats work. That doesn’t end with this war. It becomes the new operating system for international politics. Deterrence requires clarity and resolve. If you wobble when threatened, you invite more threats—possibly from others watching closely.

Dmitri Trenin:

From Moscow’s perspective, you’re hearing what Russians believe you’ve refused to hear for years: the conflict is seen as existential. When a side believes its vital interests are threatened, it signals escalation to force respect for red lines. You call it blackmail; Russians call it forcing seriousness. The naming of countries is partly about credibility—showing that escalation is not abstract. It is also about pushing Europe to act independently rather than as an extension of Washington’s strategy.

Vipin Narang:

Strategically, naming targets is a high-risk signal because it compresses ambiguity. Ambiguity can stabilize deterrence; specificity can corner leaders into either escalation or humiliation. The nuclear dimension is fundamentally about risk manipulation: making the other side believe you might do something catastrophic if pushed. It’s coercive signaling—but coercion exists inside deterrence logic. The question is whether the other side believes the threat is credible, and whether there’s a face-saving way to de-escalate without triggering further coercion.

Dmytro Kuleba:

From Ukraine’s seat, it is coercion aimed at Europe—because Europe is easier to scare than Ukraine. Ukrainians live under daily missile threats; we understand intimidation. The purpose is to make Europeans ask, “Is Ukraine worth Berlin? Is Ukraine worth London?” And that question is the weapon. But the moral hazard is obvious: if nuclear threats decide outcomes, then any aggressor with nuclear weapons can redraw borders and bully neighbors. That is not “stability.” That is permanent hostage-taking.

Nick Sasaki:

So we’ve got a shared structure: it’s coercive signaling, but it operates through deterrence logic—and the real battlefield is political will.

Let’s go one layer deeper.

The second question (asked naturally)

Nick Sasaki:

What would “backing off” even mean on each side without humiliation—what’s the smallest movement that reduces nuclear risk without rewarding threats?

Vipin Narang:

Start with the mechanics: risk reduction often looks boring—hotlines, incident-prevention, clearer doctrines, and limits on certain categories of strikes. A “backing off” that avoids humiliation is usually reciprocal and staged. For example: reduce the tempo or range of certain capabilities in exchange for specific, verifiable changes. The goal isn’t trust. It’s predictability. Even a narrow agreement that lowers miscalculation risk can matter more than grand speeches about peace.

Nina Tannenwald:

One movement is rhetorical restraint—leaders can choose not to normalize nuclear language. Another is reaffirming longstanding norms: no threats against civilian populations, no casual talk of nuclear use. But you also need channels for de-escalation that don’t look like surrender. If each side can frame a step as “responsible leadership” rather than “capitulation,” the taboo remains stronger. Humiliation is the accelerant; dignity is the firebreak.

Kori Schake:

Here’s where I’ll be blunt: you don’t reduce nuclear risk by conceding to intimidation. You reduce risk by tightening deterrence and reducing ambiguity about the consequences of escalation. But that doesn’t mean you can’t pursue guardrails. You can do both: strengthen posture, improve resilience, and simultaneously pursue communications and arms-control-like measures that reduce accident risk. The smallest movement is to make escalation costly while making restraint easy to choose.

Dmitri Trenin:

From the Russian side, “backing off” is likely tied to what Moscow sees as the strategic environment: the scale and nature of Western involvement, especially capabilities that threaten Russian territory or core assets. The smallest movement is not “abandon Ukraine,” but a shift in how the conflict is managed—less about maximalist victory narratives and more about a settlement architecture. Humiliation is avoided when the outcome is framed as “security achieved” rather than “someone defeated.”

Dmytro Kuleba:

The smallest movement that reduces nuclear risk is not to pressure Ukraine into surrendering sovereignty. It’s to reduce the incentives for escalation by making clear that nuclear threats will not win political concessions—but also by keeping channels open. Ukraine has an interest in predictable boundaries too. But I’ll insist on something: if “backing off” means Ukraine becomes a buffer state with permanently reduced rights, then you’re not reducing nuclear risk—you’re storing it. You’re teaching the next war how to start.

Nick Sasaki:

So the “non-humiliation” path looks like staged reciprocity, guardrails, predictable limits—while holding a firm line that intimidation can’t become policy.

Now the third question is the one that makes everyone squirm.

The third question (asked naturally)

Nick Sasaki:

If nuclear threats become routine—if they’re said often enough that people stop reacting—does that reduce danger because everyone gets used to it, or increase danger because the taboo erodes?

Nina Tannenwald:

It increases danger. The taboo is not a law of physics; it’s a social and political restraint. When leaders talk about nuclear use as if it’s another tool, they weaken the moral shock that helps prevent it. Normalization also degrades crisis management: if every week contains a new threat, signals lose clarity. Then in the moment of real crisis, no one can tell the difference between theater and intent. That’s how catastrophes happen.

Dmitri Trenin:

Normalization is dangerous, but there is another side: if the West genuinely believes Russia will never use nuclear weapons, that belief invites risk-taking. From Moscow’s view, part of the problem is Western disbelief. Still—making nuclear threats routine can become a trap for Russia too, because it raises expectations. If you speak in maximal terms and then do not act, you appear weak. That dynamic can pressure escalation even when it’s unwise.

Kori Schake:

Routine nuclear threats are poison. They turn international politics into hostage politics. Democracies then face internal pressure to trade away principles for calm. But the long-term consequence is worse: other states learn that nuclear coercion pays, so they pursue nuclear weapons and adopt the same tactic. That’s how you expand the nuclear club and shrink the margin for safety. We should be doing the opposite: reducing the rewards of nuclear bullying.

Vipin Narang:

Normalization increases risk through two channels. First, it blurs signals—when everything is “nuclear,” nothing is. Second, it shifts domestic politics. Leaders become locked into their own rhetoric; backing down becomes politically impossible. That’s when “audience costs” turn into strategic traps. If you want stability, you keep the nuclear channel rare, crisp, and tightly controlled—not sprayed across the information environment.

Dmytro Kuleba:

For Ukrainians, there is a cruel irony. We are asked to accept intimidation as realism. But realism without morality becomes permission for endless war. If nuclear threats become routine, then every neighbor of a nuclear power lives under permanent blackmail. And the world becomes a place where justice depends on who has the biggest arsenal. That is not a system. That is an abyss with paperwork.

Nick Sasaki:

If I summarize what I’m hearing: routine nuclear talk doesn’t calm the world—it destabilizes it by eroding the taboo, fogging signals, and trapping leaders inside their own threats.

Before we close Topic 1, I want one sentence from each of you—one thing you think the other side gets right, even if you disagree overall. Quick, honest.

Kori Schake:

Russia is right that misperception is lethal—and that great powers demand to be taken seriously.

Dmitri Trenin:

The West is right that rewarding coercion creates a precedent that will haunt everyone.

Nina Tannenwald:

Ukraine is right that normalizing nuclear threats corrodes the moral guardrails we rely on.

Vipin Narang:

Everyone is right that credibility and ambiguity are both double-edged—and we’re playing with both.

Dmytro Kuleba:

Even critics of Western policy are right about one thing: escalation risk must be managed like a live wire, not a talking point.

Nick Sasaki:

That’s Topic 1. Next, we move from language to mechanics: how escalation actually happens when nobody wants it… until suddenly it does.

Topic 2 — The Escalation Ladder: Who Controls the Next Step?

Same studio, but the lighting feels colder—more like a crisis room than a talk show. The map behind them is still blurred, but tonight you can make out shapes: the Baltic Sea, Poland, the Black Sea. A quiet hum like server racks. Everyone’s posture is a little tighter, as if the table itself is a fuse.

Nick Sasaki:

Topic 1 was about language—deterrence, coercion, taboo. Topic 2 is about mechanics: how things escalate even when leaders insist they “don’t want a wider war.” History is full of wars that nobody supposedly wanted… until they happened anyway.

Let’s do this carefully and fairly. We’ll name the risks without sensationalism.

The first question (asked naturally)

Nick Sasaki:

If this spirals, what’s the most realistic ignition point—the kind of incident that starts as “manageable” and ends up uncontrollable?

Rose Gottemoeller:

The most realistic ignition point is a chain reaction from a single strike: a missile or drone lands somewhere it wasn’t intended to land, kills people from a NATO country, and suddenly governments are forced to respond publicly. Add social media, public outrage, and domestic politics—and the space for quiet de-escalation shrinks. The second common trigger is misattribution: an attack happens, the wrong actor gets blamed in the first 48 hours, and decisions get made before facts settle.

Gen. (Ret.) Robert Kehler:

From a nuclear command-and-control perspective, the danger is when conventional conflict creates ambiguity about intent. If one side thinks the other is preparing to take out strategic assets—C2 nodes, early-warning radars, leadership sites—then you can stumble into “use-it-or-lose-it” pressures. The ignition point might not be a big headline event; it could be a pattern of strikes that begins to look like a decapitation plan.

Pavel Podvig:

I’d add a technical angle: early-warning and air-defense systems have limits, and in a tense environment they generate false alarms. Leaders don’t see the whole picture; they see fragments. If something looks like a large launch—or if communications are disrupted—decision time compresses. The smaller the decision window, the more escalation becomes a product of systems rather than judgment.

Michael McFaul:

The ignition point I worry about is deliberate testing. One side pushes a boundary to see if the other will respond—like a strike near a border, a cyberattack on critical infrastructure, or a sabotage incident that everyone pretends “we don’t know who did it.” That kind of gray-zone behavior is meant to stay below the threshold, but it can cross it fast. And when authoritarian regimes feel cornered, they sometimes choose escalation rather than humiliation.

Oleksandra Ustinova:

From Ukraine’s reality, the ignition point often looks like “normal Tuesday.” Missiles hit cities. Infrastructure gets targeted. But escalation happens when outsiders interpret events through their own red lines. For example: a strike that disrupts energy in Europe, an incident affecting foreign personnel, or political decisions to expand the range/targets allowed for Ukraine’s weapons. The war is already intense. The question is when the perimeter expands.

Nick Sasaki:

So we’ve got five plausible ignition points: spillover casualties, misattribution, ambiguous strikes on strategic systems, deliberate boundary tests, and perimeter expansion.

Now here’s where people start arguing about technology and doctrine.

The second question (asked naturally)

Nick Sasaki:

Do doctrine changes and new weapons—hypersonics, nuclear threshold talk—change the actual risk… or do they mostly change the psychology of risk?

Pavel Podvig:

Mostly psychology, but psychology drives decisions. Hypersonic systems are not magical in every way, but they compress reaction time and complicate defense planning. The risk is not that “hypersonics guarantee victory”—it’s that they create a perception of unstoppable strike capability. That can make leaders feel more vulnerable, and vulnerability is a recipe for escalation pressure.

Gen. (Ret.) Robert Kehler:

Doctrine matters because it signals what a state wants others to believe. But in a crisis, what matters is not the document—it’s the operational posture and the decision process. If doctrine lowers the threshold rhetorically, it can reduce the political friction of nuclear use. The scariest combination is compressed time, incomplete information, and leaders who feel their survival is at stake. Weapons systems and doctrine influence that sense of threat.

Rose Gottemoeller:

I want to underline “psychology with consequences.” Arms control history shows that stability comes from reducing incentives for first use and reducing misperception. If doctrinal messaging is used for coercion—especially repeated and public—it shifts the environment toward instability. Even if nobody intends to use nuclear weapons, the repeated talk increases the number of pathways where mistakes become catastrophic.

Michael McFaul:

And there’s a political effect: when a government announces a doctrinal shift, it’s often talking to multiple audiences—external adversaries, internal hardliners, and its own public. That can harden positions. If you tell your public “we must respond,” you narrow your own options later. So yes, these shifts change psychology, and psychology changes the set of moves leaders feel they’re allowed to make.

Oleksandra Ustinova:

For Ukrainians, the psychological war is constant. But I see a different asymmetry: nuclear talk is used to limit Western support. Every time the West hesitates because it fears escalation, Ukraine pays in lives and territory. So “psychology” is not abstract—it’s policy. If doctrine and weapon talk succeeds in creating fear-based restraint in Europe, that is strategic leverage. The risk is that fear becomes the main decision-maker.

Nick Sasaki:

So: doctrine and hypersonics don’t just change physics; they change the room temperature inside decision rooms—and fear can become policy.

Now the third question is the one that separates adults from performers.

The third question (asked naturally)

Nick Sasaki:

If everyone privately fears escalation, but nobody can be seen backing down, what mechanism actually stops the slide? What works when pride and domestic politics are the real battlefield?

Rose Gottemoeller:

You build narrow, verifiable agreements that allow both sides to claim responsibility rather than surrender. Crisis hotlines, deconfliction channels, and incident-prevention measures are not glamorous, but they save lives. You also need a shared understanding: certain targets—early warning, nuclear command-and-control—are “do not touch.” Even in deep hostility, some guardrails can be negotiated because both sides want to survive.

Gen. (Ret.) Robert Kehler:

One mechanism is clarity about consequences paired with a path to step back. Deterrence without an off-ramp is a trap. Off-ramps without deterrence can look like weakness. The stabilizing formula is: communicate red lines clearly, maintain credible defense, and keep a private channel open for de-escalation. Most of crisis management is about giving leaders room to choose restraint without being humiliated.

Michael McFaul:

I’ll be candid: mechanisms only work if leaders want them. In democracies, public communication matters—leaders must prepare their publics for complexity, not just slogans. In autocracies, elite politics matters—leaders must manage hardliners. Third parties can help: neutral mediators, back-channel diplomats, even unexpected intermediaries. But the essential ingredient is acknowledging that escalation is not “the other side’s problem.” It’s a shared suicide risk.

Pavel Podvig:

There’s also a structural tool: reduce the speed of decision. When you can lengthen decision windows, you reduce error. That means improving communications, avoiding attacks that can be misread as strategic, and maintaining stable alert postures. If leaders believe they have time, they make better choices. If they believe they have seconds, they make irreversible ones.

Oleksandra Ustinova:

Here’s the hard fairness point: “mechanisms” can’t mean freezing injustice permanently. If the mechanism is “everyone stops and Ukraine is left half-dismembered,” that is not stability; it is delayed escalation. Real mechanisms must include security that is lived, not promised—protection for civilians, reconstruction, accountability, and guarantees that are not paper. Otherwise you just plant the next war.

Nick Sasaki:

That last line matters: a ceasefire that stores up the next catastrophe isn’t peace—it’s postponed conflict.

Before we leave Topic 2, I want each of you to name one risk your own preferred approach tends to underestimate.

Michael McFaul:

My side can underestimate how easily coercive pressure can produce reckless escalation rather than compliance.

Rose Gottemoeller:

My world can underestimate domestic politics—how hard it is for leaders to sell restraint.

Gen. (Ret.) Robert Kehler:

Security professionals can underestimate how fast public panic can narrow leaders’ choices.

Pavel Podvig:

Analysts can underestimate human emotion—fear, pride, humiliation—inside technical systems.

Oleksandra Ustinova:

Ukraine’s friends can underestimate that “manageable escalation” is often just “someone else bleeds.”

Nick Sasaki:

That’s Topic 2: escalation often isn’t one big decision—it’s a staircase built out of misreads, pride, time pressure, and politics.

Next topic, we zoom into Europe itself: when Germany and the UK are named, what does “European security” even mean anymore?

Topic 3 — Europe as Target: NATO, Sovereignty, and the End of Old Guarantees

The studio screen shifts: not a war map now, but a blurred skyline—Berlin’s TV tower, London’s Thames bridges, a faint outline of Brussels buildings. The lighting warms slightly, but the atmosphere feels heavier, like talking about a house while hearing thunder on the roof.

Nick Sasaki:

If Germany and the UK are named in nuclear threats, that’s not just “Ukraine war news.” That’s Europe’s identity getting put on trial. So tonight we ask: what does security mean when the old assumptions start cracking?

Let’s start where it hurts.

The first question (asked naturally)

Nick Sasaki:

If Germany and the UK are explicitly named as potential targets, what happens to alliance credibility—and what happens inside Europe politically?

Malcolm Chalmers:

Alliance credibility becomes a psychological contest as much as a military one. The UK has a deterrent, but credibility also depends on political unity and the sense that allies will stand together under pressure. If publics begin to doubt that unity—or doubt that leaders are competent—then deterrence weakens. Politically, explicit targeting can create factionalism: some parties argue for doubling down, others argue for accommodation. That internal split is often what coercion aims to produce.

Wolfgang Ischinger:

Europe’s political ecosystem is already fragile—energy, migration, polarization. When nuclear threats name specific European capitals, it becomes a stress test for European cohesion. The credibility problem is twofold: NATO credibility and European credibility. NATO is a defensive alliance; if member states cannot agree on strategy, deterrence becomes a slogan. Meanwhile, European institutions—EU structures—were not designed for high-intensity war risk. So there is institutional lag.

Elbridge Colby:

We need to be realistic. Credibility is a product of capabilities and will. If European states are named and still rely heavily on American capabilities, then Europe’s credibility is entangled with America’s priorities. That can create confusion and risk. Europe has to decide what it will actually do, materially, not just rhetorically. Otherwise adversaries will see division as opportunity. Explicit targeting is often meant to force the question: are you serious about this or not?

Nathalie Tocci:

The political effect inside Europe is not only fear—it’s redefinition. Some will argue for strategic autonomy: Europe must be able to defend itself and shape its neighborhood. Others will cling tighter to the US because the alternative feels uncertain. The danger is that fear produces paralysis, and paralysis produces dependence. But dependence also creates resentment. So you can end up with a Europe both reliant on the US and angry about that reliance.

Andriy Zagorodnyuk:

From Ukraine’s point of view, alliance credibility is not theoretical—it is measured in whether Europe can hold a line when threatened. If the naming of Germany and the UK causes Europe to reduce support to Ukraine, Russia learns a lesson: nuclear intimidation works. If Europe stands firm, Russia learns the opposite. The political fight inside Europe is therefore part of the battlefield. Ukraine can’t decide that for Europe—but Europe can decide whether coercion becomes a policy lever.

Nick Sasaki:

So naming countries is about cracking unity—inside Europe and inside NATO—by turning fear into politics.

Now let’s hit the second question: sovereignty.

The second question (asked naturally)

Nick Sasaki:

Is Europe acting as a sovereign strategist here—or is Europe still a pressured theater where bigger powers shape the outcomes?

Nathalie Tocci:

Europe is both. It has agency, but it often fails to use it. Europe is a regulatory superpower, but security is different: it requires capabilities, risk tolerance, and leadership under uncertainty. When Europe doesn’t build those, it becomes a theater by default. Sovereignty isn’t a slogan; it’s a capacity. If Europe wants agency, it needs a coherent strategy that isn’t simply “follow Washington” or “appease Moscow.”

Wolfgang Ischinger:

Europe’s challenge is not lack of intelligence—it’s lack of unity. When Europe speaks with many voices, it becomes easier for external powers to deal with Europe bilaterally and play divisions. That reduces sovereignty. But Europe has moments of agency when it aligns—on sanctions, on support, on defense spending. The question is whether it can sustain alignment under stress. Naming Germany and the UK is designed to make alignment harder.

Elbridge Colby:

I’ll frame it bluntly: Europe has chosen dependence for decades because it was comfortable. The bill comes due when the world gets hard. If Europe wants sovereignty, it must accept burden, rearmament, industrial base, and political seriousness. Otherwise, Europe will remain a theater: Washington will provide the core, and adversaries will try to exploit that by targeting European cohesion. Agency comes from strength, and strength comes from choices.

Malcolm Chalmers:

There’s also a nuclear nuance. The UK has its own deterrent, and France does too—those realities shape Europe’s strategic identity. But nuclear forces do not solve every problem. They deter existential threats; they don’t manage every rung of escalation. Europe needs layered security: conventional readiness, resilience, and coherent political messaging. Sovereignty is not a single switch. It’s an ecosystem.

Andriy Zagorodnyuk:

Ukraine sees Europe’s sovereignty as a moral and strategic question. If Europe is merely a theater, then Ukraine becomes a pawn between great powers. If Europe is sovereign, it can define the outcome that makes the continent safer long-term. That includes refusing the logic that “might makes right.” Europe has agency if it chooses it. But it must decide whether it wants to be a subject or an author.

Nick Sasaki:

Okay—Europe is both agent and theater, and the deciding factor is whether it builds capacity and unity under stress.

Now the third question is the one people avoid because it forces a future.

The third question (asked naturally)

Nick Sasaki:

Looking ahead, does Europe’s security future look like tighter alignment with the US, real strategic autonomy, or fragmentation into competing national paths?

Wolfgang Ischinger:

If Europe is wise, it’s tighter alignment with the US and more European capability. It doesn’t have to be either-or. The most dangerous path is fragmentation: each country improvising its own deal, its own posture, its own fear-management. Fragmentation invites coercion because it makes Europe easier to pick apart. The best path is dual: strengthen NATO while building European capacity so the alliance becomes more balanced and credible.

Nathalie Tocci:

Strategic autonomy is not anti-American; it’s pro-European responsibility. The future should be a Europe that can act when America is distracted or divided—and still cooperate with the US when interests align. Fragmentation is not just possible; it’s already happening emotionally—different publics, different threat perceptions. The antidote is a shared narrative and shared investment. Without that, autonomy becomes a slogan and alignment becomes dependence.

Elbridge Colby:

Alignment will remain central because the US is still the anchor of NATO. But the US also has finite attention and resources. Europe should not assume America will always prioritize Europe above all else. That means Europe must prepare for scenarios where US focus shifts. If Europe doesn’t prepare, fragmentation is the default. A coherent Europe is a strategic asset. A fragmented Europe is an invitation for adversaries.

Malcolm Chalmers:

I worry about fragmentation because it can happen quietly. You don’t need a formal breakup; you just need divergent policies. Different thresholds for risk. Different willingness to spend. Different views on negotiation. Once that happens, deterrence becomes incoherent. Europe’s future will depend on whether institutions can translate threat into sustained capability—defense industry, readiness, civil resilience—not just emergency summits.

Andriy Zagorodnyuk:

From Ukraine’s perspective, fragmentation is the worst case because it turns European security into a patchwork—and patchworks have seams. Adversaries probe seams. Autonomy could be good if it increases Europe’s strength and consistency. Alignment could be good if it is reliable and principled. The key is not the label; it’s whether Europe becomes harder to coerce. Because coercion is the play.

Nick Sasaki:

So the future choice is: coherent strength—whether aligned or autonomous—versus fragmentation that makes coercion easier.

Before we close Topic 3, one last fairness check: each of you, name one thing your “camp” tends to overlook.

Elbridge Colby:

Hardliners can overlook that escalation risk is real and can’t be managed by bravado.

Nathalie Tocci:

Autonomy advocates can overlook the time it takes to build capability—and the danger of slogans without capacity.

Wolfgang Ischinger:

Institutionalists can overlook how quickly publics can turn—fear and fatigue are strategic variables now.

Malcolm Chalmers:

Deterrence thinkers can overlook that credibility is political and economic, not just military.

Andriy Zagorodnyuk:

Ukraine’s supporters can overlook that “freezing” the conflict can be a slow-motion defeat that guarantees another war.

Nick Sasaki:

That’s Topic 3: Europe is being asked—by events, by threats, by history—whether it’s a spectator, a stage, or an author.

Next, we move to the messiest battlefield of all: narrative. What gets amplified, what gets ignored, and who benefits when reality turns into content.

Topic 4 — The Information War: Fear, Propaganda, and Who Profits From Panic

The studio screen goes dark, then flickers into a collage of headlines—blurred, unreadable—like a storm of rectangles. The room feels noisier even though it’s silent, as if everyone can hear their own phone buzzing. Someone sets a glass down a little too hard.

Nick Sasaki:

If nuclear threats are also messages, then the battlefield isn’t just Ukraine—it’s people’s minds. What gets repeated, what gets censored, what gets monetized. And the hardest part: sometimes fear spreads because it’s profitable, not because it’s true.

So Topic 4 is about narrative power—on every side.

The first question (asked naturally)

Nick Sasaki:

When a claim like “Russia may nuke Germany and the UK” circulates, what’s the honest difference between warning the public and engineering panic?

Renée DiResta:

Intent and design. Warning the public is about clarity: what’s known, what’s uncertain, what should people do with the information. Engineering panic is about virality: dramatic framing, certainty without evidence, and emotional hooks that make people share before they think. The difference often shows up in the packaging: is there nuance, sourcing, and limits—or is it built to spike adrenaline?

Peter Pomerantsev:

And it’s also about audience targeting. Panic isn’t accidental; it’s often aimed. The point can be to fracture societies—make people distrust institutions, distrust allies, distrust each other. A warning tries to strengthen civic capacity. Panic tries to weaken it. In information war, the winner is not the side with the “best argument,” but the side that can shape what feels real.

Glenn Greenwald:

I’d add a fairness point: institutions often label uncomfortable reporting as “panic” or “disinformation” to protect themselves from scrutiny. So we need a consistent standard. If you’re making a claim, show evidence, show uncertainty, and show incentives. But don’t pretend that “official narratives” are automatically truthful. Many disasters happened because dissenting warnings were dismissed as irresponsible.

Anne Applebaum:

Sure, but let’s not be naïve: authoritarian systems use fear deliberately. Nuclear hints can be tools to intimidate and paralyze democracies. The goal is to make publics pressure their governments to abandon allies and accept “peace” on coercive terms. That’s a known playbook. The danger is that democracies, in trying to be open, become the easiest targets for manipulation.

Michael Tracey:

The problem is that almost everyone has incentives to hype. Media outlets profit from attention; political actors profit from outrage; think tanks profit from urgency. So the “panic vs warning” line gets blurred because escalation talk becomes content. The responsible move is to slow down: separate what was said, who said it, what authority they actually have, and what patterns of rhetoric exist over time.

Nick Sasaki:

Okay—so warning strengthens capacity; panic weakens it. And we judge by sourcing, uncertainty, incentives, and whether it helps people think or just react.

Now: censorship and platform control.

The second question (asked naturally)

Nick Sasaki:

Should platforms and governments suppress nuclear-escalation claims to avoid panic—or does that backfire by increasing distrust and conspiracy thinking?

Renée DiResta:

Blanket suppression usually backfires. It creates martyrs and reinforces “they’re hiding the truth” narratives. The better approach is context and friction: labels that add sourcing, downranking proven falsehoods, and boosting authoritative context without pretending authority is perfect. Also—teach the audience how to evaluate claims. If people feel treated like adults, trust grows.

Glenn Greenwald:

Censorship is a gift to people who want to weaponize distrust. Once you normalize suppression, you guarantee that power will be abused, often against dissent. The public has been lied to repeatedly—about wars, intelligence claims, surveillance. The solution is not more gatekeeping; it’s radical transparency and open debate.

Anne Applebaum:

Open debate is essential, but democracies have to defend themselves too. When foreign actors deliberately inject disinformation or amplify fear to destabilize societies, doing nothing is not “neutral.” It’s surrendering the information space. The key is targeting coordinated manipulation rather than punishing ordinary speech. But yes—democracies need defenses.

Peter Pomerantsev:

I think the question is: what are you optimizing for? If you optimize for “no panic,” you end up with brittle societies that can’t process reality. If you optimize for “resilience,” you teach people to live with uncertainty without collapsing into paranoia. Authoritarians exploit both extremes: panic and denial. A resilient society can hold fear and still think.

Michael Tracey:

And there’s a legitimacy issue. If the same institutions that made major errors become the arbiters of truth, skepticism will be inevitable. You can’t demand trust; you have to earn it. Context is better than suppression—but context itself must be honest about uncertainties and past failures.

Nick Sasaki:

So the middle path is: target coordinated manipulation, add context, reduce virality of falsehoods, but avoid broad censorship that turns everything into a forbidden fruit.

Now the third question—who profits.

The third question (asked naturally)

Nick Sasaki:

Who benefits when nuclear fear spreads—politically, financially, strategically—and how do we keep that from hijacking policy?

Anne Applebaum:

Strategically, coercers benefit: they want democracies to self-deter—to restrain themselves because of fear. Politically, extremists benefit because fear makes people seek strongmen or simple answers. Financially, yes—some media and some influence networks profit from heightened emotion. To keep policy sane, leaders must communicate clearly and build trust through consistency.

Peter Pomerantsev:

Fear is a currency. It can buy clicks, votes, compliance, and silence. It also allows elites to avoid accountability: “Don’t ask questions, it’s an emergency.” The antidote is not pretending fear isn’t rational—it can be rational—but building civic muscles: critical thinking, plural media ecosystems, and institutions that can admit uncertainty without collapsing.

Renée DiResta:

From a systems angle: platforms benefit from engagement; entrepreneurs benefit from ads and subscriptions; political actors benefit from mobilization. It becomes an attention marketplace where the most alarming frame wins. We can design against that: more friction before sharing, stronger provenance signals, transparent funding disclosures for political media, and a culture of “wait before you retweet reality.”

Glenn Greenwald:

And let’s not ignore the national security apparatus. Crisis narratives can expand budgets, surveillance, and secrecy. That doesn’t mean every warning is fake—it means incentives are real. The safeguard is adversarial journalism, congressional oversight, and an informed public that doesn’t outsource thinking to “officials.”

Michael Tracey:

Policy hijack happens when emotion outruns analysis. The fix is procedural: force decision-makers to articulate the strongest counterargument before acting, demand evidence thresholds for major steps, and require an “off-ramp plan” for any escalation. In other words: you don’t prevent fear; you prevent fear from being the only input.

Nick Sasaki:

So fear benefits coercers, extremists, engagement machines, and sometimes bureaucracies. The fix isn’t to deny fear—it’s to build procedures and culture that keep fear from driving the steering wheel.

Before we close Topic 4, quick fairness check—each of you name one thing your own side is tempted to do wrong in an information war.

Anne Applebaum:

My side can over-trust institutions and under-estimate the cost of censorship.

Glenn Greenwald:

My side can under-estimate foreign manipulation and treat everything as domestic propaganda.

Renée DiResta:

My side can over-focus on platforms and under-focus on political incentives and culture.

Peter Pomerantsev:

My side can become so cynical that it forgets people still need meaning and hope.

Michael Tracey:

My side can confuse contrarianism with clarity and end up amplifying noise.

Nick Sasaki:

That’s Topic 4: if the war is also informational, then “truth” needs guardrails—against panic, against censorship, and against profit-driven hysteria.

Topic 5 — The Off-Ramp Problem: Peace Without Rewarding Nuclear Coercion

The screen behind the roundtable settles into a blurred image of a negotiation room: microphones, folders, water glasses, flags out of focus. The energy shifts—less outrage, more gravity. Everyone looks like they’re holding two truths at once: fear is real, and so is pride.

Nick Sasaki:

We’ve talked about threats, escalation, Europe, and the information war. Now we reach the hardest question: how do you stop this without teaching the world that nuclear intimidation is a successful tactic?

Let’s build an off-ramp that’s realistic, fair, and doesn’t collapse under its own contradictions.

Participants: Thomas Schelling, Fiona Hill, Samuel Charap, Mary Elise Sarotte, Jeffrey Sachs

The first question (asked naturally)

Nick Sasaki:

What does a realistic off-ramp look like that lowers nuclear risk fast—without turning coercion into a winning strategy?

Thomas Schelling:

You reduce risk by trading restraints in a way that lets each side claim prudence rather than humiliation. The off-ramp must be structured so that “we avoided catastrophe” becomes the public story—not “we were forced.” The more it looks like capitulation to threats, the more you encourage future threats. So you design it as mutual risk reduction with verifiable steps.

Fiona Hill:

A realistic off-ramp starts with de-escalation measures that reduce accidental war: sustained military-to-military channels, incident prevention, and clarity around what targets are off-limits because they can be misread as strategic attacks. But it also needs a political architecture that doesn’t leave Ukraine permanently exposed. If the settlement is merely a pause before the next round, nuclear risk doesn’t go down; it simply gets deferred.

Samuel Charap:

Start small and enforceable. Ceasefire arrangements that are monitored, prisoner exchanges, humanitarian access, protection of critical infrastructure, and constraints that reduce escalation dynamics—like limiting certain strike categories. Then move to harder issues later. People want a single grand bargain, but durable deals are often layered. The big difference between “rewarding coercion” and “preventing catastrophe” is verification and sequencing.

Mary Elise Sarotte:

History warns us about settlements that normalize conquest or create permanently ambiguous security orders. A realistic off-ramp must avoid signaling that borders can be changed by force as a routine method. That doesn’t mean insisting on maximal outcomes immediately; it means building a process that doesn’t ratify coercion as a precedent.

Jeffrey Sachs:

A realistic off-ramp means returning diplomacy to the center and acknowledging that security is reciprocal. You need an immediate ceasefire framework, then negotiations addressing territorial realities, security guarantees, sanctions, and Europe’s broader security order. You also have to stop treating diplomacy as weakness. Ending wars often involves talking to adversaries, not just allies. The faster we create a credible diplomatic track, the lower the nuclear risk.

Nick Sasaki:

So we’ve got five building blocks: mutual restraints, de-escalation channels, layered enforceable steps, no normalization of conquest, and a serious diplomatic track that treats reciprocal security as real.

Now comes the question everyone fights about: guarantees.

The second question (asked naturally)

Nick Sasaki:

What kind of security guarantee for Ukraine is strong enough to deter a repeat invasion, but not so provocative that it triggers more escalation?

Samuel Charap:

Guarantees aren’t binary. Between “NATO Article 5 tomorrow” and “vague promises,” there’s a spectrum: long-term military assistance commitments, air defense integration, intelligence sharing, training pipelines, defense industrial support, and rapid resupply mechanisms. The aim is to remove the prospect of a cheap victory. You can create deterrence through capability and continuity, even if the legal form is not identical to a full treaty guarantee.

Fiona Hill:

Ukraine needs security that’s lived, not merely declared. That means resilient air defenses, protected critical infrastructure, and sustained support that can’t be switched off by political moods. But the guarantee must also be credible to Europe itself—Europe has to see Ukrainian security as part of European security. Otherwise we get “symbolic support” that fails at the moment of real pressure.

Thomas Schelling:

Deterrence is about shaping expectations. If an aggressor expects an easy success, you invite aggression. If an aggressor expects failure or unacceptable cost, you reduce it. The guarantee should make renewed attack predictably costly without cornering the adversary into believing it has only one option left. Off-ramps matter as much as tripwires.

Mary Elise Sarotte:

The guarantee will only be as strong as Europe’s capacity to sustain it. That means budgets, production, readiness, and political durability. A guarantee that depends on temporary emotions is not a guarantee. If Europe wants stability, it must institutionalize commitments so they outlast election cycles and news cycles.

Jeffrey Sachs:

The guarantee should be paired with a broader security arrangement that reduces incentives for escalation. If you create a framework where one side feels permanently threatened and the other feels permanently vulnerable, you build a war machine. A credible guarantee can exist alongside negotiated limits, transparency measures, and security provisions that lower the perceived need for extreme measures. The goal is stability, not triumphalism.

Nick Sasaki:

What I’m hearing: layered capability-based guarantees, institutionalized European capacity, deterrence that doesn’t corner, and a broader architecture that reduces permanent insecurity on both sides.

Now the toughest fairness test.

The third question (asked naturally)

Nick Sasaki:

What would you ask your own side to give up—something painful but necessary—to make an off-ramp possible?

Mary Elise Sarotte:

I’d ask Western leaders to give up moral posturing that collapses the space for negotiation. Speak honestly about complexity, costs, and tradeoffs. Also give up short-termism—security policy can’t be improvised every six months.

Samuel Charap:

I’d ask policy communities to give up maximalist war aims that are not achievable without unacceptable escalation risk. That doesn’t mean conceding principles. It means aligning objectives with reality and building mechanisms that reduce harm now while keeping long-term outcomes open.

Fiona Hill:

I’d ask Western publics to give up the illusion that this is a distant problem with distant consequences. And I’d ask leaders to stop treating Ukraine as a symbol and start treating it as a society that must survive and rebuild. On the other side, I’d ask Russia’s leadership to give up the idea that fear can buy lasting security. It can’t.

Thomas Schelling:

I’d ask everyone to give up the comfort of moral purity. Crisis bargaining is often choosing among imperfect options to prevent the worst. If you insist only on outcomes that feel emotionally satisfying, you increase the probability of outcomes that are catastrophic.

Jeffrey Sachs:

I’d ask the United States and Europe to give up the habit of seeing diplomacy as appeasement and to stop framing negotiations as betrayal. I’d ask Russia to give up imperial assumptions and accept that security can’t be built on domination. And I’d ask all sides to accept that a sustainable peace requires compromise, verification, and long-term reconstruction—not victory narratives.

Nick Sasaki:

So the sacrifices are real: less posturing, fewer maximalist fantasies, more long-term seriousness, acceptance of imperfect outcomes, and a return of diplomacy as a legitimate tool—not a taboo.

Closing beat

Nick Sasaki:

If Topic 1 was the language of threat, and Topic 2 was the staircase of escalation, Topic 3 Europe’s identity crisis, Topic 4 the narrative battlefield—then Topic 5 is the craft of getting off the ledge without teaching the world to shove people toward it.

If you want, next I can generate the full TDKI package for the 5-topic series with your keyword rules and 16:9 image prompts—unless you’d like to swap one speaker to make the “both sides” balance even sharper.

Final Thoughts by Nick Sasaki

After five topics, I keep coming back to one uncomfortable truth: nuclear danger isn’t only about weapons. It’s about incentives.

It’s about what leaders think they can get away with.

It’s about what crowds reward.

It’s about what media amplifies.

It’s about what alliances signal—intentionally or accidentally.

And it’s about how quickly fear can turn smart people into gamblers.

If a headline like “Russia will nuke UK and Germany” does anything useful, it should be this: it forces us to stop speaking in slogans and start speaking in probabilities, pathways, and prevention.

And prevention isn’t dramatic. It’s almost insulting in how uncinematic it is:

reliable backchannels

clear red-line communication

verification and restraint

stopping the “everyone must win” fantasy

and building an off-ramp that doesn’t reward intimidation but still prevents catastrophe

That’s not weakness. That’s adulthood.

Because the opposite of “strong” isn’t “compromise.”

The opposite of strong is reckless—and reckless is how history turns into ash.

If you’re watching this and you feel anxious, I get it. But don’t let anxiety make you manipulable. Let it make you serious.

We don’t need more people screaming.

We need more people thinking clearly—so the people with power have fewer excuses to gamble with the rest of us.

Short Bios:

Nick Sasaki — Creator of ImaginaryTalks and series moderator, focused on building fair, structured debates that separate claims, evidence, incentives, and practical off-ramps.

Nina Tannenwald — Political scientist known for research on the “nuclear taboo,” norms, and why nuclear use remains politically constrained despite military capabilities.

Dmitri Trenin — Russian foreign-policy analyst known for explaining Moscow’s strategic worldview, threat perceptions, and the logic Russian elites use in security debates.

Michael Kofman — Military analyst specializing in Russian and Ukrainian armed forces, known for granular assessments of battlefield realities and escalation risks.

Rose Gottemoeller — Veteran arms-control negotiator and former senior NATO/U.S. official, known for practical verification, treaty design, and risk-reduction frameworks.

Vipin Narang — Nuclear strategy scholar focused on posture, signaling, and escalation pathways, especially how doctrine shapes crisis behavior.

Herman Kahn — Cold War-era strategist famous for systematic thinking about escalation ladders, deterrence credibility, and worst-case scenario planning.

Lawrence Freedman — British historian and strategist of war and deterrence, known for clarifying how coercion, credibility, and strategic communication work in practice.

Ankit Panda — Nuclear policy writer focused on doctrine, arms control, and escalation dynamics, known for translating technical nuclear issues for broad audiences.

Pavel Podvig — Expert on nuclear forces and arms control, known for technical clarity on arsenals, delivery systems, and what different postures imply.

James Acton — Analyst of nuclear escalation and arms control, known for emphasizing misperception risks and “inadvertent escalation” traps.

Ben Wallace — Former UK defense leader associated with hard-nosed defense realism, often emphasizing deterrence, readiness, and alliance credibility.

Claudia Major — German security expert known for analysis of European defense, NATO strategy, and Germany’s evolving posture under pressure.

Ian Bond — European security analyst focused on EU/NATO policy, sanctions, and how Europe balances deterrence with escalation management.

Constanze Stelzenmüller — Transatlantic strategist known for sharp analysis of European politics, alliance cohesion, and the credibility gap between rhetoric and capacity.

Mark Leonard — European policy thinker focused on geopolitical competition and the EU’s strategic dilemmas in a harsher security environment.

Peter Pomerantsev — Analyst of propaganda and information warfare, known for how modern narratives shape public emotion and political behavior.

Anne Applebaum — Historian and journalist known for writing on authoritarian systems, disinformation, and the moral/strategic stakes for democracies.

Masha Gessen — Writer known for reporting and analysis on Russian politics, power systems, and the human consequences of authoritarian governance.

Glenn Greenwald — Journalist known for civil-liberties focus and skepticism of security-state narratives, often pressing for evidentiary standards and accountability.

Maria Ressa — Journalist known for work on disinformation ecosystems, platform incentives, and how fear-driven narratives spread across societies.

Jeffrey Sachs — Economist and policy scholar who emphasizes diplomacy and economic realities, often arguing for negotiated settlements and long-run stability.

John J. Mearsheimer — International relations scholar associated with realist theory, known for power-politics framing and critique of liberal intervention assumptions.

Stephen Walt — Foreign-policy realist known for alliance theory and analysis of how states balance threats, interests, and credibility.

Stephen Kotkin — Historian known for deep context on Russian state power, strategic culture, and the long arc behind current confrontations.

Janice Gross Stein — Conflict-management scholar known for negotiation design, crisis decision-making, and practical de-escalation pathways.

Leave a Reply