|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

What if “the day after AGI” forces a new global safety floor the way aviation forced standards—because the costs of being wrong arrive all at once?

Introduction by Demis Hassabis

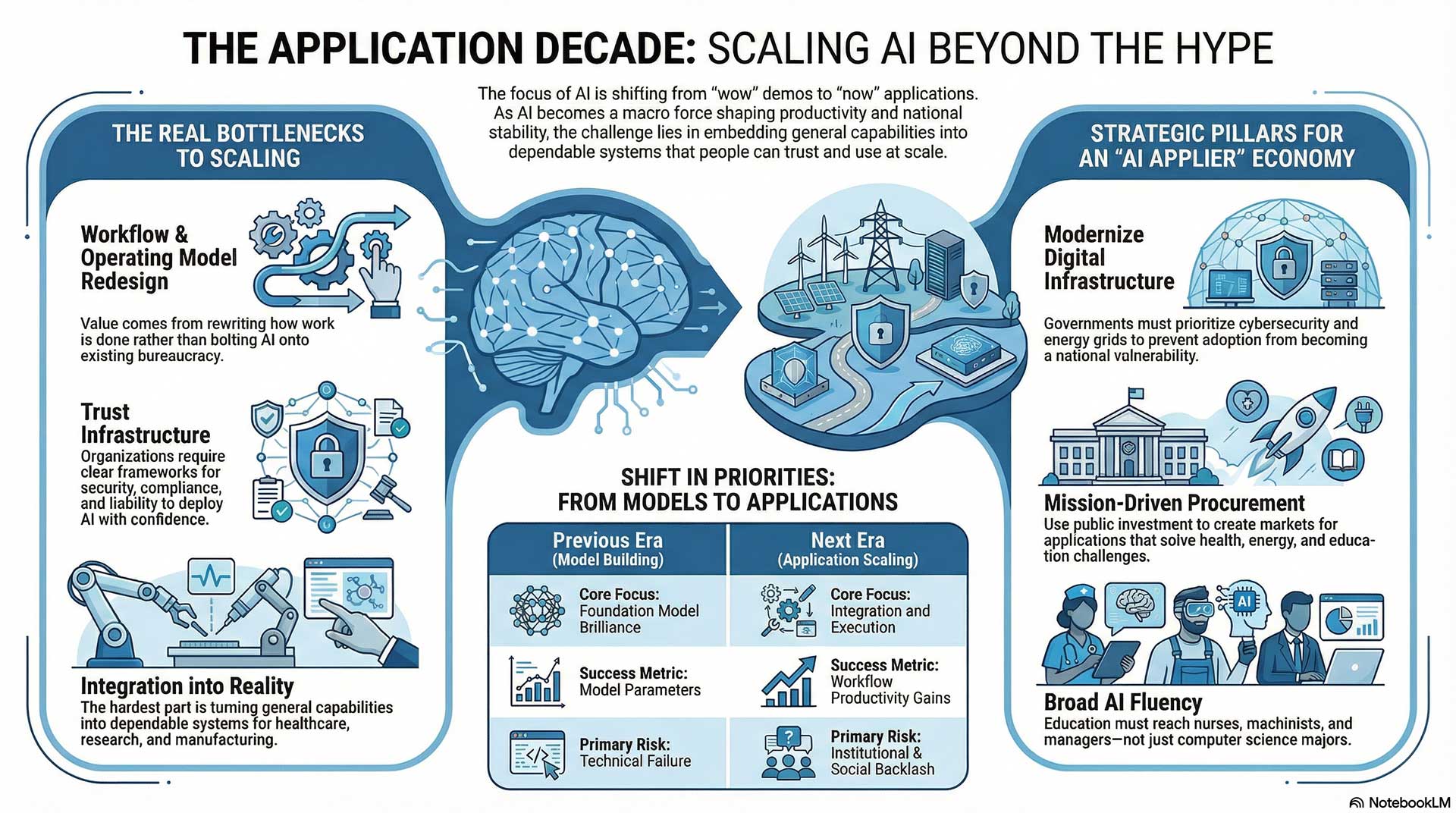

At Demis Hassabis Davos 2026, my goal was to pull the conversation out of “wow” and into “now.” AI isn’t just a technology story anymore—it’s becoming a macro force that will shape productivity, national competitiveness, science, and social stability. The biggest opportunity in front of us isn’t that everyone builds new foundation models. It’s that we take the capabilities we already have and translate them into applications at scale—systems people can rely on in healthcare, education, research, and enterprise workflows.

But scaling applications changes the stakes. When AI is embedded into real institutions, the questions become concrete: How do we make these systems robust and safe? What happens to the on-ramp for young workers if entry-level tasks get automated? Can our physical infrastructure—compute, energy, grids, chips—keep up? And if AI creates abundance, how do we ensure it doesn’t also create a legitimacy crisis where people feel the gains belong to someone else?

That’s why this series is built the way it is. It’s not “five cool topics.” It’s five stress tests for the decade: deployment at scale, the safety floor, the jobs ladder, the industrial stack, and the fairness problem. If we get those right, AI becomes a tool for expanding human capability. If we get them wrong, we’ll see backlash that slows progress and fractures trust right when coordination matters most.

(Note: This is an imaginary conversation, a creative exploration of an idea, and not a real speech or event.)

Topic 1: The Application Decade — Who Wins When AI Scales

The Davos air has that particular mix of cold and consequence—snow outside, fluorescent urgency inside. In a glass-walled side room just off the main corridor, a small roundtable sits under soft lights. No stage. No applause cues. Just five people and one question hanging over the week like weather:

If AI is becoming a macro force, who benefits—by design, or by accident?

Zanny Minton Beddoes looks down at her notes, then up at the group.

Zanny Minton Beddoes: Demis, you’ve been consistent about this: the next era won’t be everyone racing to build new foundation models. It’ll be applications at scale—AI woven into the real economy. Let’s start there, but I want it brutally practical. If the advantage shifts to applications, what becomes the true bottleneck: data, distribution, workflow redesign, regulation, talent, compute—or something we’re not naming?

Demis Hassabis: The bottleneck is integration into reality. Models are powerful, but value comes when they’re embedded into workflows—healthcare pathways, scientific discovery loops, customer operations, manufacturing systems. That requires reliable tools, evaluation, security, and domain expertise. Data matters, compute matters, but the hardest part is turning general capability into dependable systems people can trust, monitor, and improve.

Satya Nadella: Workflow redesign is the real choke point. Most organizations aren’t missing AI; they’re missing the operating model to use it. Who owns the process? How do you change incentives? How do you measure success? The winners will be those who treat AI like a new layer of productivity—rewriting how work is done, not bolting a chatbot onto yesterday’s bureaucracy.

Andrew Ng: I’d say it’s iteration speed and domain specificity. The biggest gains come from taking a real process, instrumenting it, building a targeted AI solution, and improving it in tight loops. You don’t need a new foundation model to do that. You need teams that can ship, measure, and refine. The bottleneck is not brilliance—it’s organizational muscle.

Mariana Mazzucato: The bottleneck is governance of direction. Applications at scale will follow incentives. If the incentive is short-term profit and surveillance, that’s where the talent and capital go. If the incentive includes public value—health outcomes, clean energy, productivity that raises wages—then the application decade becomes broadly beneficial. So the bottleneck is not only technical; it’s political and institutional.

Brad Smith: And the bottleneck is trust infrastructure: security, privacy, compliance, and liability. Applications at scale mean AI is making or influencing decisions everywhere. If organizations can’t answer “Who is accountable when it fails?” they will either freeze or deploy recklessly. The winning countries and companies will build clear governance, auditability, and legal frameworks that let adoption proceed with confidence.

Zanny nods once, like she’s filing “integration + workflow + iteration + governance + trust” into a single mental dashboard.

Zanny Minton Beddoes: Good. Now let’s push into the uncomfortable part. If the application decade is where the value is, does that concentrate power in a few platforms—cloud, distribution, data—or does it create a long tail of new companies and new jobs? In other words: is this an economic broadening, or a funnel?

Mariana Mazzucato: Left to default dynamics, it becomes a funnel. Platforms capture rents because they control infrastructure and access. But it doesn’t have to be that way. We can shape it: public procurement that rewards innovation and diffusion, interoperability requirements, and mission-driven partnerships where public investment comes with conditions—like open standards or shared benefits. The long tail exists only if policy makes space for it.

Satya Nadella: It will be both. Platforms will matter because compute and distribution matter. But the opportunity for the long tail is real—because every industry has workflows that can be reimagined. The difference is whether organizations can build on top of platforms without being locked in. That’s why openness—APIs, standards, choice—becomes central. The real risk is not platform power; it’s closed ecosystems that prevent competition.

Andrew Ng: I’m optimistic on the long tail. Most value is in specific, messy, unglamorous problems—insurance claims, factory defects, medical coding, logistics exceptions. Startups and internal teams can win there. But we need to stop fetishizing giant models as the only “real” AI. The real innovation is in applying AI in thousands of narrow contexts. That creates companies, services, and jobs—if we invest in builders, not just in models.

Brad Smith: Concentration is a legitimate risk, especially if regulation ends up written in a way only the largest firms can comply with. Then you unintentionally legislate a monopoly. If we want a broad ecosystem, rules must be scalable: clear standards, but not paperwork so heavy only a handful can survive. And we need competition policy that understands AI markets—where distribution and default settings can quietly become dominance.

Demis Hassabis: I think there’s enormous room for broadening, but the long tail only thrives if we solve reliability and evaluation. If applications are fragile, only the biggest players can afford the failure costs. If applications are dependable, you unlock experimentation everywhere. So the path to broad prosperity runs through technical robustness and safety practices that become widely usable, not boutique.

Zanny glances toward the glass wall, where the faint silhouettes of conference traffic pass like fish in an aquarium. Then she turns back, sharper.

Zanny Minton Beddoes: Third question, and I want it framed as advice a prime minister or CEO could actually act on this year. If applications at scale is the game, what should governments do now so their economy becomes an “AI applier” rather than a dependency? Not a wish list—your top moves.

Brad Smith: Three things. First, invest in digital infrastructure and cybersecurity so adoption doesn’t become national vulnerability. Second, create clear rules on privacy, liability, and procurement so companies can deploy responsibly without legal paralysis. Third, modernize education and workforce systems to teach AI fluency across roles—not just computer science majors, but nurses, machinists, teachers, and managers.

Mariana Mazzucato: I would start with mission-driven deployment. Pick national missions—health productivity, energy efficiency, public service modernization—and use public procurement to create markets for good applications. Make public investment conditional: transparency, accountability, and diffusion. Also, don’t just subsidize tech; build the institutions that steer it—data trusts, public interest research, and measurement of outcomes.

Andrew Ng: Build talent pipelines and remove friction for builders. Fund practical AI education, support applied research partnerships with industry, and create regulatory sandboxes where companies can test responsibly. Most importantly: digitize government services and data systems. You can’t apply AI on top of paper processes. If the state modernizes itself, the private sector learns faster too.

Satya Nadella: Governments should do what great platform builders do: create the conditions for scaling. That means modernizing public sector workflows, setting interoperability standards, and enabling trusted data-sharing frameworks. It also means focusing on diffusion—helping small and mid-sized businesses adopt AI, not just celebrating a few national champions. The winners are the economies that raise overall productivity, not just market caps.

Demis Hassabis: I’d add a strategic science component. The highest-leverage applications might be in discovery—materials, medicine, energy systems—where AI accelerates research loops. Governments can invest in shared compute for public-good research, in evaluation benchmarks, and in safety tooling that becomes standard. If you want to avoid dependency, you don’t need to build the biggest model—you need to build the strongest ecosystem for applied innovation and trustworthy deployment.

Zanny lets the last answer land. The room feels quieter, but not calmer—more like the moment after you’ve seen the map clearly and realized it’s not abstract.

Zanny Minton Beddoes: So the application decade isn’t about who has the flashiest demo. It’s about who can integrate AI into reality—safely, competitively, and at scale. The bottleneck is not genius; it’s execution. The risk is not only displacement; it’s concentration without accountability. And the policy challenge is not to “win AI” in headlines, but to build an economy that can absorb AI as a productivity layer without tearing its social fabric.

She looks around the table, almost like she’s checking whether anyone wants to disagree with the stakes.

Nobody does.

Outside, Davos keeps moving. Inside, the argument has quietly shifted from technology to power—because once AI becomes a macro force, “applications” stop being a product category and start being a governing problem.

Topic 2: The Day After AGI — Safety, Power, and the Missing Ingredients

The room is smaller than it should be for a conversation this big. A Davos side corridor, a quiet glass box, five chairs too close together—like the future is forcing intimacy.

On the table: a blank notepad and a single phrase, written neatly, almost politely:

“WHAT’S STILL MISSING?”

Zanny Minton Beddoes looks around the table the way an editor looks at a draft that could change public policy.

Zanny Minton Beddoes: Demis, you’ve said something that’s both reassuring and unsettling—that AGI feels clearer, but there are still “missing ingredients.” I want to start there. What are those missing ingredients, really? Is it reasoning, planning, embodiment, reliability, alignment—or something deeper we’re not even measuring well yet?

Demis Hassabis: It’s several things, and they’re intertwined. We have impressive pattern intelligence, but the robustness and reliability under distribution shift is not where it needs to be. Long-horizon planning, consistent reasoning, and the ability to ground and verify answers—those are still uneven. And then there’s the question of agency: as systems become more capable, how do we keep them steerable, predictable, and aligned with human intent? That’s not one ingredient; it’s a stack.

Yoshua Bengio: I would emphasize reliability and truthfulness as first-class objectives. We’ve optimized for next-token prediction and capability demonstrations, but not enough for honesty and safety by design. A missing ingredient is a principled approach to uncertainty—systems that know when they don’t know, and that behave safely when they’re unsure. Another missing ingredient is societal: institutions and incentives that prioritize safety rather than speed alone.

Dario Amodei: I see the missing ingredients as two categories: technical and governance. Technically, we need better interpretability, better evaluation, and better alignment methods that scale with capability. We also need systems that are less brittle and less prone to deceptive or manipulative behavior as they become more agentic. Governance-wise, we need norms and guardrails that keep the competition from turning safety into a casualty.

Helen Toner: I’d add that we’re missing honest measurement. We don’t have a shared, widely trusted way to evaluate “dangerous capability” across models, especially as they become more tool-using and more autonomous. Another missing ingredient is clarity about thresholds: what capabilities trigger what obligations? Without that, we’re arguing about vibes while the systems keep improving.

Ian Hogarth: The missing ingredient is also accountability. If something goes wrong—misuse, accidents, economic disruption—who is responsible in practice? Companies, states, standards bodies? Right now, the incentives are to sprint. The missing ingredient is an enforcement mechanism that’s credible enough that “we take safety seriously” becomes a real constraint, not a marketing line.

Zanny pauses, letting the phrase “missing ingredients” stop sounding poetic and start sounding like a checklist with consequences.

Zanny Minton Beddoes: Let’s go to the question that governments secretly hate. Timelines. If some people say “five to ten years” and others say “sooner,” policy can swing between paralysis and panic. How should governments plan without either panic or denial—when the timeline itself is uncertain?

Helen Toner: Plan by capability, not by date. You don’t need to predict the exact year of AGI to set policies for models that can write code, design chemicals, or automate large portions of knowledge work. Governments should build trigger-based frameworks: when capability X appears, policy Y activates—audits, reporting, restrictions, or safety tests. That’s how you avoid both hysteria and complacency.

Demis Hassabis: Exactly. The right approach is to prepare for rapid advances while keeping institutions steady. We should invest in safety research, in evaluation standards, and in capacity for governments to understand the technology. Not every policy needs to be maximal today, but the infrastructure—testing, oversight, expertise—must be built now. If we wait for certainty, we lose.

Ian Hogarth: I would add: treat it like national risk management. You don’t wait for a hurricane landfall to define evacuation routes. You build plans, stress-test them, and run simulations. Governments should create dedicated capability within the state—technical teams that can inspect, evaluate, and respond quickly—so decisions aren’t improvised in the middle of a crisis.

Dario Amodei: And avoid the trap of using uncertainty as an excuse to do nothing. Even if AGI takes longer, the systems we have now are already changing labor markets, information ecosystems, and security landscapes. Planning without panic means acting on what’s already here: require safety testing, fund interpretability, improve incident reporting, and create channels for international coordination. These steps are useful whether the timeline is short or long.

Yoshua Bengio: The danger is that timelines become a political football. One side uses “soon” to justify reckless moves, another uses “later” to justify ignoring the risks. The correct stance is: the uncertainty itself increases the need for precautions. Because if you’re wrong on the optimistic side, you may not get a second chance.

Zanny leans back, then forward again—the tell that the next question isn’t abstract. It’s about power.

Zanny Minton Beddoes: Last question. Suppose we accept the reality: capabilities will keep improving, trust is thin, competition is fierce, and the consequences are global. What is the minimum global safety protocol that’s realistic—not utopian—and who enforces it?

Ian Hogarth: Minimum protocol: mandatory frontier-model registration, third-party evaluation for dangerous capabilities, and secure reporting of incidents and near-misses. Add compute tracking at the extreme end—not for everyone, but for the frontier where risks scale. Enforcement has to be a mix: national regulators with real teeth, and international coordination that creates consequences for noncompliance—access to markets, compute supply chains, and partnerships.

Helen Toner: I’d say: common evaluation standards, transparency requirements for frontier developers, and independent audits—like aviation safety, but adapted. We also need red lines for certain high-risk deployments. Enforcement starts nationally, but it must be interoperable internationally. If standards differ wildly, the weakest regime becomes the default.

Dario Amodei: I agree with both. We need an international “floor,” not a perfect global government. That floor includes: safety testing before deployment, rigorous evaluation of misuse potential, and mechanisms for model rollback or throttling when needed. Enforcement happens through a combination of regulation and industry commitments—but regulation must lead, because voluntary norms collapse under competitive pressure.

Yoshua Bengio: And the protocol must prioritize safety research and openness around it. Safety shouldn’t be proprietary in the way capabilities are. We need shared benchmarks, shared methods, and funding for independent research. Enforcement is not only law—it’s also legitimacy: societies must expect and demand safety proofs the way they demand safety in medicine and engineering.

Demis Hassabis: The protocol must be practical and not freeze innovation. I’d focus on robust evaluation, best-practice safety engineering, and clear governance around deployment. If we do this well, we can unlock enormous benefits while reducing tail risks. Enforcement will start with national regulators, but it will work best when aligned internationally—shared standards, shared testing, and shared incentives so that the safe path is also the competitive path.

Zanny closes her notebook, not with satisfaction—more like a judge ending a hearing with new urgency in her eyes.

Zanny Minton Beddoes: What I’m hearing is strangely consistent for a room of people who disagree on half the internet. The “day after AGI” isn’t a Hollywood moment. It’s a governance moment. The missing ingredients are reliability, evaluation, and accountability. The right planning model is capability-triggered, not calendar-driven. And the minimum safety protocol is an enforceable floor: registration, testing, audits, incident reporting, and international interoperability.

She looks around the table one last time.

Zanny Minton Beddoes: If applications are the next decade, this is the foundation under them. Without it, “at scale” doesn’t mean prosperity. It means amplified risk.

Outside, Davos continues its confident buzz. Inside, the room feels quieter—because they’ve all just admitted the same thing, in different words:

The technology is accelerating. The questions are human. And the world is still deciding whether it wants rules before it wants regret.

Topic 3: The Jobs Shock — Productivity Boom or Middle-Class Squeeze

A Davos lounge that’s supposed to feel calming: soft chairs, warm lighting, art that looks like “future.” But the conversation has the raw edge of a factory floor. Because when AI becomes a macro force, the first social question isn’t “Can it do cool things?” It’s:

Who still has a ladder?

Gillian Tett sits at the head of the table like she’s about to map a hidden system—because she is.

Gillian Tett: Demis, the AI conversation is shifting from demos to macro. The most anxious macro question is jobs. Some leaders warn we’re heading into an “AI tsunami,” especially for entry-level work. So let’s start with the first critical question: what’s the most realistic scenario—mass displacement, task reshaping, wage compression, or something more subtle?

Kristalina Georgieva: The most realistic near-term scenario is disruption concentrated in certain tasks and roles—especially entry-level knowledge work. It’s not that every job disappears. It’s that the first rung becomes unstable: junior analysts, assistants, basic coding roles, routine legal drafting, customer support. When that on-ramp erodes, the long-term damage is larger than the short-term job count suggests.

Daron Acemoglu: I agree, and I’ll sharpen it: wage compression is a major risk. If AI raises productivity but the gains accrue mostly to capital and a few highly skilled workers, the middle class gets squeezed. The scenario depends on choices. AI can augment workers—raising wages and productivity—or it can replace workers—raising profits while weakening bargaining power. Markets don’t automatically choose the good path.

Erik Brynjolfsson: The realistic scenario is “task reshaping” on a massive scale. Many jobs will change more than they vanish. But the transition can still be brutal. The key variable is diffusion speed: if AI adoption spreads faster than organizations retrain and redesign work, you get short-term dislocation and long-term productivity. Whether society experiences that as boom or trauma depends on how we manage the transition.

Fei-Fei Li: And we must not collapse “jobs” into “office jobs.” AI affects physical-world work too, through logistics, manufacturing optimization, robotics, and scheduling. The scenario is uneven: some workers gain powerful tools; others face increased surveillance and speed-up. The question is not only employment—it’s dignity and agency in work.

Demis Hassabis: I’d say the big story is: a productivity layer is arriving. Some tasks will be automated; many will be transformed. But the macro force comes from scale and speed. The difference between prosperity and squeeze is whether we adapt institutions—education, training, labor markets—fast enough. AI won’t politely wait for policy.

Gillian writes “ON-RAMP” in her notes and underlines it twice.

Gillian Tett: Second question. Policy that “sounds nice” is endless. I want what actually works at scale. Reskilling, wage insurance, portable benefits, reduced workweek, tax changes, apprenticeship models—pick the realistic mix. What can a government implement without collapsing under politics and debt?

Daron Acemoglu: Start with incentives that push AI toward augmentation rather than replacement. Tax policy and procurement can reward technologies that raise worker productivity and wages. Also strengthen competition and reduce monopoly power; otherwise, the gains will concentrate. For workers: expand training, but don’t romanticize it—training works best when paired with real job pathways and employer commitment.

Kristalina Georgieva: Portable benefits and targeted support are feasible. Wage insurance can soften transitions—helping workers move without falling into poverty. Reskilling must be tied to labor market needs. And the state must invest in modernizing public services—so the government itself becomes a model “AI applier,” not a slow bureaucracy watching the private sector reshape society alone.

Erik Brynjolfsson: Wage insurance plus “training embedded in work” is a scalable model. Traditional retraining often fails because it’s detached from real tasks. We need apprenticeship-style pathways where workers learn while producing. Also, expand access to AI tools so workers can become more productive—don’t gate them behind corporate hierarchies. The biggest missed opportunity is not job loss—it’s failing to raise everyone’s productivity.

Fei-Fei Li: Guardrails matter too. If workplaces deploy AI in ways that increase surveillance or dehumanize labor, you will get backlash. We need worker-centered design principles, transparency, and rights—especially for algorithmic management. Policy isn’t only about training; it’s about protecting dignity. Without that, “productivity” becomes a synonym for extraction.

Demis Hassabis: I’d add: invest in education reform early—teach AI literacy broadly, and focus on human strengths: critical thinking, creativity, interpersonal intelligence. Also, build public-private partnerships to accelerate applied innovation in sectors that create good jobs—healthcare, climate tech, infrastructure. The goal isn’t to freeze change; it’s to guide it so benefits spread.

Gillian looks up with that exact “here’s the real knife” expression.

Gillian Tett: Third question. If AI becomes faster and bigger than previous revolutions, what becomes society’s new on-ramp for young people? Because if entry-level roles shrink, you don’t just lose jobs—you lose the path to competence, identity, and adulthood.

Erik Brynjolfsson: We redesign entry-level work to be “AI-assisted apprenticeship.” Instead of juniors doing rote tasks to learn, they use AI for the rote part and spend more time on judgment, interpretation, and communication—with tight feedback from mentors. AI can compress learning curves if we design work that way. If we don’t, we’ll end up with a generation that’s credentialed but under-experienced.

Daron Acemoglu: And we must force organizations to keep training pipelines. If firms use AI to eliminate the junior layer, they are stealing from the future labor pool. Policy can nudge this: tax incentives for apprenticeships, procurement preferences for firms that train, and even regulation for certain sectors. Without intentional design, the on-ramp collapses.

Fei-Fei Li: The on-ramp must include human-centered skills and real-world practice. We should expand paid placements in healthcare, education, climate adaptation, community infrastructure—areas where people are needed and where AI can help but not replace. If we only create on-ramps inside tech firms, inequality grows. We need broad civic on-ramps.

Kristalina Georgieva: I worry about a split society: a small group who learns to command AI systems and a large group who becomes precarious. The on-ramp must be accessible: public AI literacy, practical training, and pathways into stable work. If we fail, the macro shock becomes political shock.

Demis Hassabis: I think we can build a better ladder, but we have to be deliberate. If AI handles low-level tasks, young people can move faster into higher-level thinking—if mentorship, evaluation, and real responsibility still exist. The worst outcome would be using AI to remove opportunity, instead of using it to accelerate learning.

Gillian closes her notebook—still not an ending, more like a warning label.

Gillian Tett: So the jobs shock isn’t a simple “robots take jobs” story. It’s a ladder story. It’s the entry-level rung, wage dynamics, dignity in work, and whether productivity gains spread or concentrate.

She looks around the table.

Gillian Tett: If the application decade is real, the question becomes: do we use AI to widen opportunity—or to automate the path that creates opportunity?

Outside, Davos keeps selling the future. Inside, the room is quietly deciding whether the future includes most people—or just the people who already have a seat at the table.

Topic 4: Compute, Energy, and the New Industrial Stack

Davos at night feels like a paradox: snow-soft streets outside, hard-edged negotiations inside. In a quiet side room, the table is bare except for five objects that look harmless until you realize they’re the new geopolitics:

A tiny chip wafer. A miniature transmission tower. A plain cooling pipe segment. A blank permitting folder. A small data-center rack model.

Zanny Minton Beddoes glances at them like an editor looking at the real headline nobody wants to print.

Zanny Minton Beddoes: We keep talking about AI like it’s mostly software. But the truth is physical: compute, electricity, grids, chips, cooling, permits. Here’s the first question. If AI is scaling into a macro force, what’s the “energy reality check” leaders keep avoiding?

Fatih Birol: The reality check is simple: demand is rising fast, and grids are not built for speed. Generation is one problem, but transmission and permitting are often the choke points. Leaders talk about AI as a productivity miracle, but every miracle has an input bill. If you do not plan for the power, AI becomes a constraint, not an advantage.

Jensen Huang: The reality check is that compute is not abstract—it’s industrial. You can’t conjure capacity out of speeches. We’re entering a world where intelligence is manufactured, and manufacturing needs energy, factories, supply chains, and long-term planning. Leaders avoid saying it because it sounds like “industrial policy,” but that’s exactly what it is.

Ursula von der Leyen: The reality check for Europe is competitiveness. If energy is expensive and permitting is slow, we will import the future instead of building it. We must modernize grids, accelerate clean energy deployment, and coordinate investment. Otherwise, we face a new dependency—this time not only on fuels, but on compute and the infrastructure that powers it.

Sam Altman: I’ll say it bluntly: compute is the new scarce resource, and energy is the ceiling. If we want AI to be broadly beneficial, we have to treat power infrastructure like a national priority—because the demand curve doesn’t negotiate. The leaders who avoid that reality will find their AI ambitions colliding with physical bottlenecks.

Demis Hassabis: And the reality check is efficiency. Scaling isn’t only “more.” It’s smarter use of resources—better algorithms, more efficient hardware, and targeted applications where AI creates real value. Leaders avoid the nuance. They want a simple story: “AI will transform everything.” It will—but only if the industrial foundation can support it.

Zanny nods once, then pivots—because the second question is where the politics starts.

Zanny Minton Beddoes: Second question. Does the compute race force governments into a new kind of industrial policy—chips, grids, permitting, workforce—whether they like it or not? And if yes, what’s the smart version that avoids waste and cronyism?

Ursula von der Leyen: The smart version is coordinated and rules-based. Europe must streamline permitting, build interconnections, and mobilize private capital toward strategic infrastructure. Industrial policy should not mean picking favorites blindly. It should mean creating a single market for scale, reducing fragmentation, and ensuring the regulatory environment rewards investment and innovation.

Sam Altman: Yes, it forces it. The question is whether it’s proactive and transparent, or reactive and messy. The smart version focuses on bottlenecks: permitting speed, energy build-out, chip capacity, and safety standards. If governments try to micromanage outcomes, they’ll fail. If they build the platform—energy, compute access, and clear rules—innovation follows.

Fatih Birol: Industrial policy is already here; it’s just not always called that. The smart version is to treat the grid as strategic infrastructure and plan for long-term demand. That means investment frameworks, faster approvals, and workforce development. It also means realism: you need reliable baseload, flexible generation, storage, and demand management. It’s a system problem, not a single technology problem.

Demis Hassabis: I think the smartest industrial policy is enabling policy: invest in foundational infrastructure, support research and safety, and avoid suffocating diffusion. We also need shared benchmarks and evaluation. If we want broad benefit, we must support not only frontier labs, but the application ecosystem—healthcare systems, science institutions, public services—so AI isn’t trapped inside a few firms.

Jensen Huang: I’ll add: speed is everything. The race isn’t only between companies; it’s between systems that can build. If permits take years, you lose. The smart policy is predictable, fast, and technology-neutral: clear standards, clear timelines, and massive investment in the grid. And don’t forget manufacturing capacity—chips and advanced packaging take years to expand.

Zanny’s tone stays calm, but her eyes sharpen.

Zanny Minton Beddoes: Third question. Someone always pays. If AI becomes an industrial stack—compute, energy, data centers—who bears the cost? Consumers through prices? Taxpayers through subsidies? Cloud giants through capex? Or some new model like usage fees or “AI taxes”?

Sam Altman: The biggest costs will be borne by the builders up front—capex is unavoidable—but over time it should translate into lower costs through productivity gains. The danger is uneven distribution: if only a few capture the upside, everyone else experiences the bill. I’m wary of blunt “AI taxes,” but I’m not wary of frameworks that ensure benefits spread—like broad access, diffusion support, and public-good investment.

Fatih Birol: Consumers already bear costs when energy systems are underbuilt—through volatility and insecurity. The best outcome is long-term investment that lowers volatility and improves reliability. If we rely only on subsidies, we risk backlash. If we rely only on private capital, we risk underinvestment in grids and public infrastructure. The cost-sharing must be balanced—and politically explainable.

Jensen Huang: The cost is real, but the return is enormous if deployed well. The simplest truth is: those who build the infrastructure capture advantage. Companies will pay to build because the demand is there. Governments should focus on removing friction, not replacing the market—except where infrastructure is naturally public, like grids and permitting. If you make the environment buildable, private capital flows.

Demis Hassabis: We should think in terms of social ROI. If the stack enables breakthroughs in medicine, energy efficiency, and science, the returns can justify investment—but only if we guide applications toward real societal value, not just novelty. Cost allocation should reflect that: some private, some public, with accountability and measurement. Otherwise, trust collapses.

Ursula von der Leyen: Europe must ensure that citizens experience benefits, not only costs. That means competition, openness, and preventing monopolistic rent capture. It also means investing in public capacity—skills, digital infrastructure, and energy security—so people see AI as improving daily life, not merely consuming resources. If the bill comes without visible benefit, legitimacy breaks.

Zanny closes her notebook, but the room doesn’t feel finished—more like it’s finally named the real architecture underneath the AI story.

Zanny Minton Beddoes: So the industrial stack is the hidden plot: grids, chips, cooling, permits, workforce, and the political story of who pays and who gains. If leaders want “AI at scale,” they’re not buying software—they’re signing up for a new kind of nation-building.

And in this decade, the countries and companies that win won’t just be the ones with the best models.

They’ll be the ones that can build.

Topic 5: Radical Abundance — The Promise, the Distribution, the Legitimacy

The Davos lights outside look like a constellation—wealth scattered across a dark sky. Inside, the room is warm and quiet in the way that makes hard ideas feel even sharper.

On the table sits a single blank card. Someone has written one sentence in plain ink:

“ABUNDANCE FOR WHOM?”

Fareed Zakaria sits forward, calm voice, eyes like a spotlight that doesn’t blink.

Fareed Zakaria: Demis, your view of the moment—AI shifting from flashy demos to applications at scale—has a hopeful subtext: productivity, discovery, medicine, maybe even a kind of radical abundance. But history has a habit: new abundance can still produce new inequality. So let’s start with the first critical question. If AI creates radical abundance, what stops it from becoming radical inequality?

Esther Duflo: Nothing stops it by default. Technology doesn’t distribute itself. The benefits go first to those with capital, skills, and access. If AI lowers costs but wages stagnate, you get cheaper goods and a weaker social contract. Preventing radical inequality requires intentional policy: education, redistribution where needed, and public goods that make access real—not just theoretical.

Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala: And global inequality matters too. If AI becomes a productivity engine concentrated in a few countries, you get a new kind of dependency: others become buyers of intelligence rather than builders of capacity. That’s destabilizing. Preventing radical inequality requires diffusion—technology transfer, capacity building, and rules that keep markets open enough for participation, not just consumption.

Tim Berners-Lee: I’ll take a structural view: if AI runs on closed platforms, closed data, and proprietary systems, abundance becomes rent extraction. You can have extraordinary innovation and still end up with a feudal distribution model—where a few owners charge everyone else for access. The solution is openness: standards, interoperability, and rights over data and identity. Without those, abundance becomes control.

Mustafa Suleyman: I think the honest answer is: we need a new social settlement. AI could be the greatest force for abundance—health breakthroughs, personalized education, productivity leaps—but it will also accelerate dislocation. If people feel “the system got richer and I got replaced,” backlash will be fierce. So we need mechanisms that share benefits: safety nets that fit this era, and policies that keep work dignified even as tasks shift.

Demis Hassabis: I’m optimistic about the upside, but I agree with the premise. Abundance doesn’t automatically translate to fairness. The way to prevent radical inequality is to focus on broad diffusion of applications—so productivity gains happen across many sectors and communities—and to invest in public-good deployments: healthcare, science, education, climate solutions. Also, we need governance that ensures safe and responsible use, so trust grows alongside capability.

Fareed nods slowly, then presses into the second question—because this is the part where “cool technology” turns into a constitutional problem.

Fareed Zakaria: Second question. If we accept that distribution won’t happen automatically, what’s the new rules layer for AI? Is it rights, audits, liability, provenance, public-option infrastructure—what actually creates legitimacy?

Tim Berners-Lee: Start with digital rights and standards. People need control over their data, identity, and consent. We need provenance—knowing what is real, what is synthetic, and what is manipulated. Interoperability prevents lock-in. And we should have public-interest infrastructure—open protocols—so society isn’t fully dependent on a handful of private systems.

Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala: From the global governance angle: transparency and fairness. If AI systems influence trade, productivity, and security, we need rules that reduce discrimination and protect access for developing countries. We also need cooperation on standards so the world doesn’t split into incompatible AI blocs. Legitimacy requires that the benefits and participation are not restricted to a small club.

Esther Duflo: Legitimacy also requires accountability: when AI harms someone—wrongful denial of service, discrimination, misinformation—there must be recourse. Audits matter. Liability matters. But so does public capacity: governments need technical competence to regulate, and citizens need tools to understand. Otherwise the rules are either captured or ignored.

Mustafa Suleyman: I think we’ll need both hard regulation and social policy. Hard regulation: audits, safety standards, and guardrails for high-risk domains. Social policy: a modernized safety net and education system. If people feel protected and included, legitimacy grows. If they feel exposed, every mistake becomes a political explosion.

Demis Hassabis: I’d emphasize evaluation and safety as part of legitimacy. People need to trust that systems are robust and not reckless. That means benchmarks, testing, transparency around limitations, and mechanisms for correcting failures. Then add the policy layer: data governance, accountability, and broad access to the benefits—so legitimacy isn’t a slogan but an experience.

Fareed lets that settle, then pivots to the final question—the one that Davos always dances around because it implies coordination in an era of distrust.

Fareed Zakaria: Third question. Which institutions can still coordinate global cooperation when trust is thin—but interdependence is unavoidable? In other words, who has any authority left to keep AI from becoming a new arms race of capability and inequality?

Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala: Institutions can still work, but they must adapt. The WTO is built for trade, not AI—but the principle holds: predictable rules reduce conflict. For AI, we need coalitions of the willing—countries and companies agreeing on standards, transparency, and fair access. We also need capacity-building so developing countries can participate meaningfully.

Tim Berners-Lee: I’m wary of “authority” in one body. Better is a network of institutions anchored by open standards. If the core protocols are open, cooperation doesn’t require perfect trust—it requires shared self-interest. Build the web layer right, and coordination becomes easier. Build it closed, and you get fragmentation and control.

Esther Duflo: We also need legitimacy at home. Global coordination fails when citizens don’t trust their own institutions. So the pathway to global cooperation includes domestic competence: transparent regulation, evidence-based policy, and protection for the vulnerable. Without that, leaders will retreat into national posturing.

Mustafa Suleyman: The realist answer is: coordination will be imperfect. But we can still create safety floors—shared testing norms, incident reporting, and agreements on certain red lines. Think of it as “minimum viable cooperation.” It won’t be utopia. But it can be enough to prevent worst-case dynamics if major actors participate.

Demis Hassabis: I agree with “minimum viable cooperation.” We should be ambitious about the benefits and sober about the risks. Internationally, we can align on safety standards and evaluation. Domestically, we can build systems that diffuse AI benefits widely. If we succeed, AI becomes a macro force for prosperity and discovery. If we fail, it becomes a macro force for division.

Fareed closes his notebook, gaze steady.

Fareed Zakaria: Then radical abundance isn’t just an engineering problem. It’s a legitimacy problem. The difference between a golden age and a backlash era will be whether people feel included in the upside, protected from the downside, and able to trust the systems shaping their lives.

Outside, the Davos lights still glitter. But the room has turned that glitter into a question with teeth:

Abundance for whom?

Final Thoughts by Demis Hassabis

The truth is, we’re going to build extraordinary capabilities—this is one of those moments in history where the curve is bending and it won’t unbend. So the key question is not “Will AI advance?” It’s whether we can advance our institutions, norms, and infrastructure fast enough to match it.

I’m optimistic, especially about what AI can do for science and medicine—accelerating discovery, making expertise more accessible, and helping solve problems we’ve struggled with for decades. But optimism has to be disciplined. The application decade requires reliability, evaluation, and accountability to become normal engineering practice. It requires governments and companies to protect the jobs ladder—especially the entry-level on-ramp—so a generation isn’t locked out of competence. It requires the industrial stack—energy, grids, compute, chips—to be treated as real-world strategy, not an afterthought. And it requires legitimacy: people must feel the benefits in their lives, not only hear about them in speeches.

If we build responsibly, AI can widen opportunity and accelerate progress. If we don’t, we won’t just waste value—we’ll create social and geopolitical instability that makes the technology harder to use well. In that sense, the future isn’t determined by a single breakthrough. It’s determined by whether we can scale wisdom at the same pace as capability.

Short Bios:

Demis Hassabis — CEO of Google DeepMind, focused on building advanced AI systems and translating frontier capability into real-world applications at scale, with an emphasis on safety and scientific progress.

Zanny Minton Beddoes — Editor-in-chief of The Economist, known for sharp macro framing and for translating complex shifts—finance, geopolitics, technology—into clear “what actually changes next” questions.

Andrew Ng — AI researcher and educator known for popularizing practical, applied AI; emphasizes iteration speed, domain-specific deployment, and building “AI builders” rather than chasing only bigger models.

Satya Nadella — CEO of Microsoft, associated with platform-scale deployment and enterprise transformation; often frames AI as a workflow revolution that rewrites how organizations operate.

Mariana Mazzucato — Economist known for mission-driven innovation policy; focuses on shaping incentives so technology serves public value, not only private rent capture.

Brad Smith — President of Microsoft, a leading voice on tech governance; emphasizes trust infrastructure—security, compliance, accountability, and scalable regulation that doesn’t crush competition.

Yoshua Bengio — AI pioneer and researcher; advocates for rigorous safety research, honesty and uncertainty awareness in AI systems, and governance that prioritizes risk reduction alongside innovation.

Dario Amodei — CEO of Anthropic; focuses on alignment, evaluation, and safety practices for frontier models, pushing for enforceable safety standards that survive competitive pressure.

Helen Toner — AI governance researcher; emphasizes measurement, capability thresholds, and “policy by trigger” frameworks so governments can act without relying on perfect timeline predictions.

Ian Hogarth — Technology investor and AI policy voice; focused on accountability, enforcement mechanisms, and building state capacity to manage frontier AI risks realistically.

Gillian Tett — Financial Times editor and anthropologist; known for mapping the hidden social systems behind markets and institutions, especially when technology reshapes power and work.

Kristalina Georgieva — Managing Director of the IMF; focuses on global stability, growth, and the distributional effects of shocks—warning that AI could hit jobs and inequality unevenly.

Daron Acemoglu — Economist focused on institutions, power, and technology’s impact on wages; argues outcomes depend on incentives—AI can augment workers or squeeze them.

Erik Brynjolfsson — Economist studying technology and productivity; emphasizes task redesign and diffusion, arguing AI can raise broad productivity if paired with smart organizational change.

Fei-Fei Li — AI scientist focused on human-centered AI; emphasizes dignity, rights, and real-world impacts, cautioning against surveillance-heavy deployment and uneven benefits.

Fatih Birol — Executive Director of the IEA; focuses on energy security and the physical constraints behind economic transitions, including the grid and power requirements behind AI growth.

Jensen Huang — CEO of NVIDIA; frames AI as an industrial revolution in “manufacturing intelligence,” stressing compute supply chains, chips, and the speed of building capacity.

Ursula von der Leyen — President of the European Commission; pushes European competitiveness and strategic autonomy across industry, energy, and security in response to shifting global realities.

Sam Altman — CEO of OpenAI; focuses on scaling AI systems and the compute/energy realities behind frontier progress, while engaging in debates over safety, governance, and economic disruption.

Fareed Zakaria — Global affairs host and author; known for connecting geopolitics with legitimacy and social cohesion, especially as technology reshapes power.

Esther Duflo — Economist known for evidence-based anti-poverty policy; emphasizes that distribution is not automatic and that legitimacy requires real access and accountability.

Mustafa Suleyman — AI executive and author; emphasizes social settlement, safety floors, and the need for credible governance as AI diffusion accelerates.

Tim Berners-Lee — Inventor of the World Wide Web; advocates for open standards, data rights, and interoperability so “abundance” doesn’t become platform rent extraction.

Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala — WTO Director-General; focuses on rules-based cooperation and preventing fragmentation, with attention to fairness for developing countries in a new AI-shaped economy.

Leave a Reply