|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

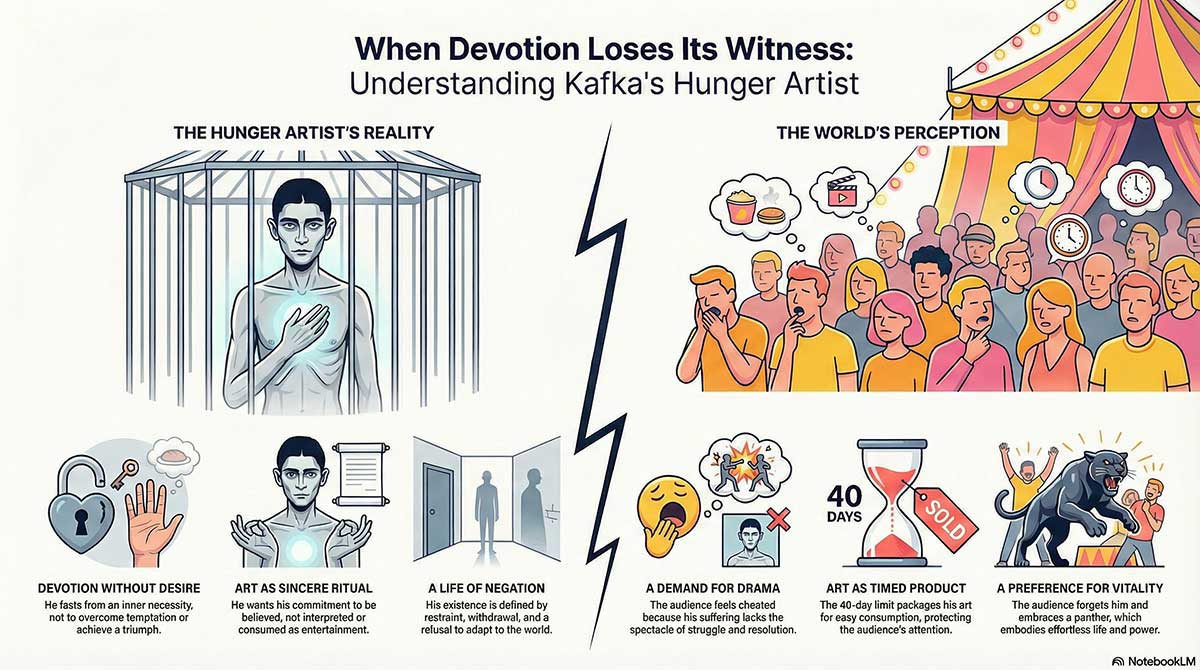

What if Kafka wrote A Hunger Artist as a prophecy of creators who would starve quietly while louder lives thrived?

Introduction by Franz Kafka

I did not write A Hunger Artist to praise suffering, nor to condemn the world that watches it.

I wrote it because there are people who live by an inner necessity that does not translate. Their devotion is not chosen for effect, and it does not seek admiration. It simply persists, even when the conditions that once gave it meaning have disappeared.

The hunger artist does not fast to astonish. He fasts because he cannot do otherwise. And this is precisely what troubles those who observe him. We expect suffering to justify itself through struggle, temptation, or transformation. His does none of these things. It continues quietly, faithfully, and without triumph.

What unsettles is not his weakness, but his consistency. He does not adapt. He does not improve. He does not learn how to live differently. And when the audience grows tired, he does not protest. He simply continues, unnoticed.

This story is not about cruelty. It is about a mismatch. A world that measures meaning by attention, and a man whose life cannot survive under that measure. When devotion outlives recognition, it does not become noble. It becomes invisible.

If this tale feels cold, it is because it is honest. The hunger artist does not ask to be understood. He asks only that his necessity be taken seriously — and even that request arrives too late.

(Note: This is an imaginary conversation, a creative exploration of an idea, and not a real speech or event.)

Topic 1 - Devotion Without Desire

Participants:

- Franz Kafka

- Albert Camus

- Gilles Deleuze

- Stanley Corngold

- Susan Sontag

Moderator: Nick Sasaki

Nick Sasaki (opening)

The hunger artist insists on one thing above all else.

Not recognition.

Not applause.

Not even understanding.

He insists that his fasting is sincere.

And yet, near the end of his life, he confesses something devastating:

he fasted not because it was difficult, but because he could never find food he liked.

So I want to begin with the most uncomfortable question.

Nick Sasaki

If the hunger artist fasts because it is easy rather than difficult, does that make his devotion purer—or hollow?

Franz Kafka

I never imagined him as heroic.

He does not overcome temptation. He simply lacks it. That absence is neither virtue nor vice—it is a condition. His suffering is not chosen as a challenge; it is endured as necessity.

What disturbs people is not that he starves, but that his starvation contains no triumph.

Albert Camus

That is precisely why he belongs to the absurd.

Devotion usually presupposes struggle. The hunger artist removes struggle from the equation. He does not conquer desire; he reveals its absence. And without desire, suffering loses its redemptive meaning.

He is sincere, yes—but sincerity without revolt risks becoming sterile.

Stanley Corngold

I would be careful not to call him hollow too quickly.

Kafka’s figures often live inside compulsions they do not fully understand. The hunger artist’s fasting is sincere precisely because it lacks justification. He does not perform for meaning; he performs because he cannot do otherwise.

That sincerity, however, is unreadable to others—and perhaps even to himself.

Susan Sontag

What unsettles me is how badly we want his suffering to mean something.

We assume devotion must be dramatic, resistant, or productive. When we discover that his fasting is easy, we feel cheated—as if meaning were owed to us.

Perhaps the discomfort lies not in his emptiness, but in our demand that suffering justify itself.

Gilles Deleuze

I see neither purity nor hollowness.

The hunger artist is not negating desire; he is operating on a different register of it. His fasting is not heroic, but it is consistent. He repeats what he is, without transcendence.

The problem is that repetition without transformation becomes invisible in a world that only recognizes struggle.

Nick Sasaki

That brings us to the second question.

Nick Sasaki

Is sincerity still meaningful when it lacks struggle, desire, or temptation?

Albert Camus

Without struggle, sincerity loses its tension.

In the absurd condition, meaning arises when one resists despair while knowing resistance will fail. The hunger artist does not resist. He simply continues. That continuation may be honest—but honesty alone does not create meaning.

Susan Sontag

I’m not convinced meaning must be earned through struggle.

That idea is itself a moral narrative we impose. The hunger artist refuses drama. He refuses transformation. His sincerity is flat—and that flatness may be what makes him intolerable.

We don’t know how to value devotion that doesn’t climax.

Stanley Corngold

Kafka often exposes how modern meaning depends on visible effort.

The hunger artist’s sincerity lacks spectacle. He does not grow, repent, or collapse in a way that reassures us. His constancy feels meaningless because it offers no arc.

Gilles Deleuze

Struggle is a narrative device.

The hunger artist lives outside narrative progression. His sincerity is not toward an end—it is immanent. And immanence, without recognition, looks like nothing at all.

Franz Kafka

I would say this:

He is sincere, but sincerity is not enough to save him.

Nick Sasaki

Which leads to the final question for this topic.

Nick Sasaki

Can a life devoted to one absolute practice still be authentic if it excludes pleasure altogether?

Susan Sontag

Authenticity does not require pleasure—but it does require awareness.

The hunger artist understands himself too late. When he finally admits why he fasted, the confession is devastating precisely because it reveals a life lived without alternatives.

Albert Camus

A life without pleasure risks becoming an abdication.

Not immoral—just unfinished. The hunger artist never confronts life; he bypasses it.

Gilles Deleuze

Pleasure is not the measure.

Vitality is. And vitality requires connection, transformation, and difference. The hunger artist negates difference by repeating himself endlessly.

Stanley Corngold

Yet Kafka never mocks him.

The hunger artist’s tragedy is not that he lacked pleasure, but that the world had no language to receive his devotion.

Franz Kafka

He lived faithfully.

That may not be enough for meaning—but it was enough for him.

Nick Sasaki (closing)

The hunger artist does not fail because he is insincere.

He fails because sincerity alone cannot survive without desire, struggle, or recognition.

And perhaps Kafka’s quiet warning is this:

a life can be utterly devoted—and still starve.

Topic 2 - Art, Audience, and Misunderstanding

Participants:

- Walter Benjamin

- Theodor W. Adorno

- Susan Sontag

- George Steiner

- Stanley Corngold

Moderator: Nick Sasaki

Nick Sasaki (opening)

The hunger artist’s greatest complaint is not pain.

It’s suspicion.

The audience doubts him. The guards watch him. The managers limit him.

And eventually, the crowd simply stops caring.

So let’s begin with the central tension.

Nick Sasaki

Does art require an audience to have meaning—or does the audience inevitably distort it?

Walter Benjamin

Modern art is born into mediation.

Once art becomes spectacle, it invites inspection, doubt, and management. The hunger artist’s suffering is no longer an experience; it is a display. And displays invite skepticism.

Meaning does not vanish without an audience—but it does change. It becomes vulnerable to the conditions of attention.

Theodor W. Adorno

I would go further.

The audience does not merely distort art—it disciplines it. The hunger artist’s sincerity is unacceptable because it resists consumption. Forty days is not a neutral limit; it is a market correction.

Art that cannot be consumed on schedule becomes intolerable.

Susan Sontag

I want to push back slightly.

We often blame the audience too easily. The hunger artist also insists on being seen on his terms. He refuses interpretation, explanation, and variation. That rigidity creates a gulf.

Perhaps the failure is mutual.

Stanley Corngold

Kafka is precise here.

The hunger artist wants recognition without translation. He wants to be believed without being understood. That is an impossible demand in any public art.

The audience does not fail because it misunderstands him; misunderstanding is inevitable.

George Steiner

And yet, misunderstanding is not trivial.

There are works that demand a level of patience, seriousness, and humility that audiences may not possess. When that capacity erodes culturally, certain kinds of art simply become orphaned.

The hunger artist belongs to a tradition that has lost its readers.

Nick Sasaki

That leads naturally to the next question.

Nick Sasaki

Is the hunger artist misunderstood because his art is too deep—or because it asks for the wrong kind of attention?

Theodor W. Adorno

Depth is not the issue.

The problem is that his art refuses reconciliation. It offers no catharsis, no resolution, no pleasure. In a culture oriented toward entertainment, such refusal appears hostile.

Depth without pleasure becomes socially unintelligible.

Susan Sontag

But we should be careful not to romanticize difficulty.

The hunger artist demands an attention that is pure, sustained, and unquestioning. That is not depth—it is austerity. And austerity, when enforced, alienates as much as it enlightens.

Walter Benjamin

The wrong attention is still attention.

The tragedy is not misunderstanding, but the collapse of ritual around the act. Once fasting loses its symbolic frame, it becomes merely odd. Meaning requires context, not just sincerity.

Stanley Corngold

Kafka stages a mismatch.

The hunger artist belongs to an earlier symbolic economy. The audience belongs to a later one. Neither is wrong, but the overlap has vanished.

George Steiner

This is the fate of much serious art.

It does not fail because it lacks depth, but because the conditions for receiving depth no longer exist.

Nick Sasaki

Which brings us to the final question for this topic.

Nick Sasaki

When art is misread, is the failure the artist’s, the audience’s, or unavoidable?

Stanley Corngold

Unavoidable.

Kafka’s world is one where meaning fractures. The hunger artist is not wrong, and the audience is not malicious. They simply inhabit incompatible frameworks.

Susan Sontag

I would say responsibility is shared.

The artist refuses compromise. The audience refuses patience. Between those refusals, meaning evaporates.

Theodor W. Adorno

Failure is structural.

Capitalism reorganizes attention itself. Under such conditions, art that resists simplification will inevitably be misread or ignored.

Walter Benjamin

Misreading is not always loss.

Sometimes it is the only way art survives—through fragments, rumors, and distortions. Total understanding is rare.

George Steiner

Yet there remains a moral residue.

When a culture repeatedly fails to hear its most demanding voices, something impoverishes—not just art, but thought itself.

Nick Sasaki (closing)

The hunger artist does not ask for applause.

He asks to be believed.

And Kafka leaves us with an unsettling possibility:

that art can be sincere, demanding, and necessary—and still be lost, not through hostility, but through indifference.

Topic 3 - The Forty-Day Limit

Participants:

- Walter Benjamin

- Theodor W. Adorno

- Susan Sontag

- Milan Kundera

- Rainer Stach

Moderator: Nick Sasaki

Nick Sasaki (opening)

The hunger artist’s deepest frustration isn’t hunger.

It’s the clock.

Again and again, he insists he could go longer—far longer—yet the manager ends the performance at forty days. Not because the artist is finished, but because the audience is.

So let me begin here.

Nick Sasaki

Does placing limits on devotion protect art—or quietly destroy it?

Rainer Stach

Historically, the forty-day limit is pragmatic.

It’s not imposed out of cruelty, but calculation. The manager believes he is safeguarding both the artist and the audience. Yet Kafka shows us something more insidious: once devotion is regulated for consumption, its inner necessity is no longer decisive.

The limit protects the spectacle, not the art.

Walter Benjamin

Limits transform ritual into product.

Originally, fasting carried symbolic weight—religious, moral, communal. The forty-day cap strips fasting of its ritual gravity and replaces it with scheduling. Time becomes the organizer of meaning.

What is protected is not devotion, but attention.

Theodor W. Adorno

Let’s be precise.

The forty-day limit is an act of domination. It disciplines sincerity into digestible form. Art is permitted only insofar as it can be completed, packaged, and replaced.

Anything that exceeds the attention span of the market must be curtailed—or erased.

Susan Sontag

I agree, but I want to complicate this.

Unlimited devotion is not automatically virtuous. The hunger artist’s desire to go on indefinitely may itself be a refusal to engage the world. Limits can sometimes force encounter, not prevent it.

The problem is not limits per se, but who sets them—and why.

Milan Kundera

What strikes me is the betrayal of seriousness.

The forty-day limit turns suffering into a genre. It reassures the audience that depth will not last too long, that seriousness will not disrupt pleasure. This is the beginning of kitsch: pain without consequence.

Nick Sasaki

That brings us directly to the second question.

Nick Sasaki

Is compromise with popularity a form of survival—or the beginning of betrayal?

Milan Kundera

Compromise is always seductive.

At first, it feels like adaptation. But soon it demands repetition, simplification, and emotional predictability. The hunger artist compromises once—and finds himself trapped in a performance that no longer belongs to him.

Betrayal rarely announces itself. It arrives disguised as success.

Susan Sontag

Yet survival matters.

Artists do not exist outside society. Total refusal can become a form of purity that isolates itself into irrelevance. The hunger artist’s tragedy may be that he refuses compromise so completely that he leaves no bridge to others.

Theodor W. Adorno

That bridge is an illusion.

Compromise under capitalism does not preserve art; it transforms it into entertainment. Survival achieved by surrendering form is survival in name only.

The hunger artist survives physically for a time—but his art is already dead.

Walter Benjamin

Still, the tension is real.

Modern artists must negotiate visibility. The tragedy Kafka shows is not compromise itself, but a system that allows no alternative rhythms of attention—only the market’s.

Rainer Stach

Kafka understood this personally.

He wrote knowing his work might never find a public. The hunger artist is not naïve; he knows the cost of refusal. What he cannot accept is a version of survival that invalidates the reason he began.

Nick Sasaki

Which leads us to the final question for this topic.

Nick Sasaki

When meaning must be packaged for consumption, what is the first thing lost?

Theodor W. Adorno

Time.

Real meaning requires duration—dwelling, resistance, difficulty. Packaging compresses experience into manageable units. Depth does not survive compression.

Walter Benjamin

Aura is lost.

Not as nostalgia, but as presence. When experience is formatted for repetition, its singularity dissolves.

Susan Sontag

Attention is lost.

Not quantity, but quality. Packaged meaning invites reaction, not contemplation.

Milan Kundera

Ambiguity is lost.

And with it, freedom. What remains is sensation without consequence.

Rainer Stach

What is lost, ultimately, is trust.

Trust that art can demand more than we are immediately willing to give.

Nick Sasaki (closing)

The forty-day limit is not a detail.

It is Kafka’s quiet indictment of a world that insists even devotion must know when to stop.

And once meaning learns to end on schedule, it rarely returns in full.

Topic 4 - Tragedy, Choice, or Fate?

Participants:

- Franz Kafka

- Albert Camus

- Hannah Arendt

- Stanley Corngold

- Rainer Stach

Moderator: Nick Sasaki

Nick Sasaki (opening)

By the time the hunger artist is forgotten in the circus, many readers feel torn.

Is this a tragedy inflicted by a changing world?

Or is it a life shaped—perhaps ruined—by his own inability to choose differently?

Kafka never answers this directly. So let’s ask it plainly.

Nick Sasaki

Is the hunger artist a victim of changing times, or someone incapable of adapting to life?

Rainer Stach

From a historical perspective, both are true.

The hunger artist belongs to a cultural moment that has vanished. His art loses relevance not because it is fraudulent, but because the world no longer has room for it. Yet Kafka is careful: the hunger artist also shows no capacity for reinvention.

He does not adapt because adaptation would require a self he does not possess.

Stanley Corngold

Kafka’s characters are rarely adaptable in the modern sense.

The hunger artist is not resistant to change out of pride; he is structurally incapable of desiring what the world offers. Adaptation presumes alternative values. He has none.

Calling this failure risks misunderstanding the nature of his predicament.

Albert Camus

Still, incapacity does not erase responsibility.

In the absurd condition, we confront a world that refuses meaning. The question is not whether meaning exists, but how one responds to its absence. The hunger artist responds by continuing a practice that no longer speaks.

That is fidelity—but also evasion.

Franz Kafka

I did not imagine him as choosing between options.

He has no options. What he does is not adaptation or refusal—it is continuation. The world changes; he does not. That mismatch is not moral failure. It is the condition of the story.

Hannah Arendt

What concerns me is how easily we mistake incapacity for innocence.

The hunger artist withdraws from the public realm of action. He does not seek to appear among others except as spectacle. In doing so, he relinquishes the space where responsibility emerges.

Victimhood and responsibility are not mutually exclusive.

Nick Sasaki

That leads directly to the second question.

Nick Sasaki

At what point does devotion become self-inflicted suffering rather than tragic fate?

Albert Camus

It becomes self-inflicted when it no longer confronts reality.

Tragedy involves conflict—between self and world. The hunger artist abandons conflict. He persists in a ritual emptied of resistance. Without revolt, suffering hardens into habit.

Stanley Corngold

Yet Kafka resists moralizing that persistence.

The hunger artist’s suffering is not chosen as punishment or martyrdom. It emerges from inner necessity. To call it self-inflicted risks imposing ethical categories Kafka deliberately avoids.

Hannah Arendt

But necessity does not absolve withdrawal from judgment.

When suffering becomes invisible, it ceases to challenge the world. Tragic fate has public consequence; private endurance does not. At that point, devotion risks becoming solipsistic.

Rainer Stach

Kafka himself feared this.

He worried that his writing might become inwardly perfect and outwardly irrelevant. The hunger artist embodies that fear—a devotion refined to the point of disappearance.

Franz Kafka

Suffering is neither justified nor condemned.

It simply continues—until no one remains to witness it.

Nick Sasaki

Which brings us to the final question of this topic.

Nick Sasaki

Is the hunger artist responsible for his own disappearance—or is responsibility meaningless in a world that no longer sees him?

Hannah Arendt

Responsibility does not disappear with recognition.

Even in obscurity, one remains answerable for how one appears—or fails to appear—in the world. The hunger artist chooses invisibility as much as it is imposed upon him.

Albert Camus

I would say responsibility persists even when meaning collapses.

The hunger artist’s refusal to seek another form of life is a decision, even if it feels inevitable. Absurdity does not remove agency; it sharpens it.

Stanley Corngold

Kafka complicates this.

Agency in Kafka is fragmented, partial, often illusory. Responsibility exists—but it cannot fully account for outcomes. That is the unease his stories leave behind.

Rainer Stach

The hunger artist disappears because the world moves on—and because he never follows.

Blame alone explains nothing. Fate alone explains too much. Kafka holds both in tension.

Franz Kafka

He was faithful.

Whether faithfulness is enough—that question I leave unanswered.

Nick Sasaki (closing)

The hunger artist’s life does not collapse in scandal or defiance.

It simply fades.

Kafka leaves us with a troubling ambiguity: a world that no longer sees him, and a man who never learned how to be seen otherwise.

Perhaps tragedy today is not destruction—but disappearance.

Topic 5 - The Panther and the Question of Life

Participants:

- Gilles Deleuze

- Hannah Arendt

- Milan Kundera

- George Steiner

- Elias Canetti

Moderator: Nick Sasaki

Nick Sasaki (opening)

Kafka ends the story quietly—but decisively.

The hunger artist dies unnoticed.

In his place, the circus installs a panther.

The crowd gathers immediately. The animal radiates power, appetite, and joy. Where the hunger artist repelled attention, the panther commands it effortlessly.

So let’s begin with the most unsettling contrast.

Nick Sasaki

Why does the panther captivate audiences instantly, while the hunger artist is forgotten?

Elias Canetti

Because power is visible.

The panther embodies a surplus of life—strength without explanation, presence without apology. Crowds are drawn to what asserts itself. The hunger artist withdraws. Withdrawal does not gather power; it dissolves it.

Hannah Arendt

The panther appears.

That is crucial. It occupies the public realm fully—moving, eating, asserting itself among others. The hunger artist retreats into invisibility. In political terms, he abandons the space where meaning can be shared.

What does not appear cannot endure.

George Steiner

Yet this comparison should trouble us.

The panther is pure immediacy. It asks nothing of the audience except admiration. The hunger artist demands patience, interpretation, and seriousness. A culture that chooses the panther may be choosing life—but a diminished version of thought.

Gilles Deleuze

I would frame it differently.

The panther is pure affirmation. It does not negate. It does not explain. It lives. The hunger artist negates life through repetition without difference. That negation exhausts itself.

Audiences follow vitality instinctively.

Milan Kundera

And yet vitality alone is not wisdom.

The panther replaces the hunger artist not because it is better—but because it is easier. Joy without reflection is always more popular than suffering that asks questions.

Nick Sasaki

That brings us to the deeper philosophical fault line.

Nick Sasaki

Is life affirmed through appetite and instinct—or through restraint and negation?

Gilles Deleuze

Life is affirmed through creation and difference.

Restraint that produces transformation can be vital. Restraint that only repeats negation becomes sterile. The hunger artist does not transform himself—he empties himself.

The panther creates nothing, but it lives fully.

George Steiner

There is a danger here.

If we equate life solely with appetite, we risk abandoning the spiritual dimension of human existence. Restraint has historically been a source of meaning, discipline, and transcendence.

Kafka is not mocking restraint—he is mourning its loss of resonance.

Elias Canetti

But restraint without power invites erasure.

The hunger artist’s fasting gives him no leverage. He cannot command attention, fear, or reverence. Power flows toward what asserts itself.

Life does not wait for permission.

Hannah Arendt

Restraint must re-enter the world to matter.

When it withdraws entirely, it becomes private virtue—ethically interesting, politically irrelevant. The hunger artist’s asceticism never returns to the shared space of meaning.

Milan Kundera

Perhaps Kafka is showing us a tragic imbalance.

Pure appetite lacks depth. Pure restraint lacks life. Modernity no longer knows how to hold both.

Nick Sasaki

Which leads us to the final question of the entire WSI.

Nick Sasaki

If devotion goes unseen and unremembered, does it still count as a meaningful life?

George Steiner

Meaning requires transmission.

A life that leaves no trace—no word, no gesture received by another—risks dissolving into silence. The hunger artist’s tragedy is not his devotion, but its disappearance without echo.

Hannah Arendt

Meaning emerges between people.

Without appearance, remembrance, or narrative, even the most sincere life remains unfinished. The hunger artist’s devotion never becomes a story others can carry forward.

Elias Canetti

A life may be sincere—and still powerless.

History remembers force, movement, and impact. The hunger artist leaves none. Meaning without consequence fades quickly.

Gilles Deleuze

Meaning is not a ledger.

But life that negates itself without transformation eventually collapses inward. The hunger artist’s devotion consumes itself completely.

Milan Kundera

Kafka leaves us with no comfort.

The hunger artist lived faithfully—and it was not enough. The panther lives joyfully—and is celebrated. Between them lies a question modern life still cannot answer.

Nick Sasaki (final closing)

Kafka does not tell us to become panthers.

Nor does he sanctify starvation.

He shows us a world that no longer knows how to receive devotion—and a man who never learned how to live otherwise.

Perhaps the final hunger is not for food, but for a form of life where sincerity, vitality, and recognition no longer cancel each other out.

Final Thoughts by Franz Kafka

The hunger artist dies without ceremony, and no one mourns him.

In his place, a panther appears — powerful, radiant, and immediately loved. The crowd returns. Life resumes. Nothing seems lost.

This is not irony. It is not mockery. It is observation.

The panther does not explain itself. It does not ask to be believed. It eats, moves, lives — and that is enough. The hunger artist required patience, faith, and seriousness. The panther requires none of these things.

I do not offer the panther as a solution. Nor do I sanctify the hunger artist. I leave them beside one another so the reader may feel the distance between devotion and vitality, sincerity and survival.

A life can be faithful and still vanish.

A life can be vibrant and leave nothing behind.

What disappears in this story is not suffering, but recognition. And perhaps that is the quiet truth modern life struggles to face: that sincerity alone does not secure meaning, and that devotion without witnesses fades as easily as it is forgotten.

I leave the hunger artist where he belongs — not redeemed, not accused, but seen at last for what he was: a man who lived entirely within his necessity, and was unable to live anywhere else.

Short Bios:

Franz Kafka

An Austrian writer whose works explore alienation, devotion, and the quiet terror of existing within systems that cannot explain themselves. His stories often portray inner necessity colliding with an indifferent world.

Albert Camus

A French philosopher and writer known for articulating the absurd condition of modern life. His work examines meaning, responsibility, and rebellion in a world that offers no guarantees.

Gilles Deleuze

A French philosopher who reimagined desire, repetition, and life as creative force. His ideas illuminate Kafka’s characters as figures of persistence rather than psychological failure.

Susan Sontag

An American essayist celebrated for her clarity, moral seriousness, and resistance to over-interpretation. She challenged how audiences consume suffering, art, and meaning.

Stanley Corngold

One of the most respected Kafka scholars in the English-speaking world. His work focuses on Kafka’s language, irony, and resistance to moral or psychological simplification.

Walter Benjamin

A German philosopher and cultural critic whose writing explores art, spectatorship, memory, and modernity. His insights help frame the hunger artist within changing economies of attention.

Theodor W. Adorno

A German philosopher and critic of mass culture who examined how capitalism reshapes art, attention, and sincerity. His work highlights the tension between authenticity and consumption.

George Steiner

A literary critic and essayist concerned with meaning, transmission, and cultural memory. He explored what happens when serious art loses its audience.

Milan Kundera

A novelist and essayist whose work reflects on kitsch, seriousness, and the betrayal of depth in modern life. His perspective bridges art, irony, and human fragility.

Rainer Stach

Kafka’s leading biographer, known for his careful historical grounding and resistance to mythologizing. His work situates Kafka’s stories within lived experience and personal anxiety.

Nick Sasaki

Founder of ImaginaryTalks, a creative platform where literature, philosophy, and history meet through carefully crafted imaginary conversations. His work focuses on helping readers rediscover classic ideas as living dialogues that speak directly to modern inner life, meaning, and identity.

Leave a Reply