|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

What if today’s students learned life skills from real-world builders and thinkers?

Introduction by Nick Sasaki

We are still using a school system that was designed for a different century.

It was built for an era when information was scarce, careers were stable, and success meant following instructions, memorizing content, and fitting into a standardized path. It made sense when the goal was to produce reliable workers for predictable institutions.

But look at the world now.

Information is infinite, attention is under attack, AI is rewriting the value of many skills, and social media is shaping identity before a child even knows what identity is. Meanwhile, too many students move through school without mastering reading, without learning how money works, without learning how to regulate emotions, and without learning how to communicate under pressure. They graduate with credentials but not competence, with anxiety but not direction.

When teenagers cannot read and begin acting out, stealing, or chasing dangerous status, that is not a mystery and it is not a moral failure of youth. It is a failure of adults to update the system. We kept the same structure for decades and then blamed kids for not thriving inside it.

The old model is mostly built around passive learning:

Sit still. Listen. Memorize. Test. Forget. Repeat.

It treats mistakes as penalties instead of feedback, and it often rewards compliance more than capability. It also separates school from life, as if students should wait until adulthood to learn how to earn, how to think, how to handle stress, how to build healthy habits, and how to choose good relationships.

The need for change is no longer optional. It is urgent.

So this imaginary conversation is not about minor improvements. It is about building a new educational operating system that is both fun and truly educational in the only way that matters: students can use it immediately, even while they are still in school.

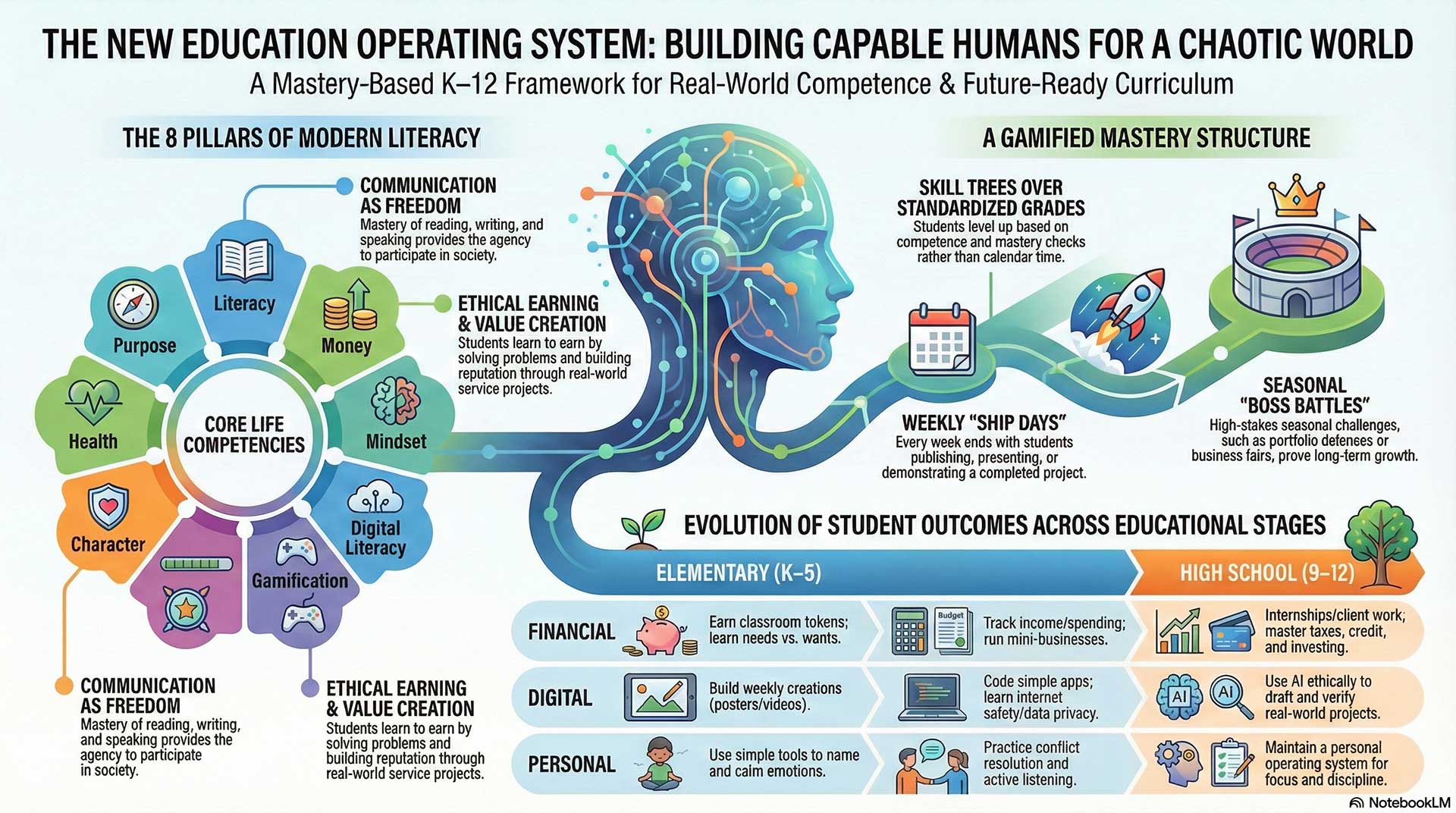

Here is the school system we are proposing, in one sentence:

A mastery-based, gamified, project-driven K–12 system that trains students to become capable humans who can read, communicate, earn ethically, self-regulate, create with technology, live with character, protect their health and attention, and navigate life with purpose.

We do it through eight life subjects that cover the full reality of modern living:

- Literacy and Communication Power

- Money, Economics, and Ethical Earning

- Mindset, Habits, and Emotional Fitness

- Digital Creation, AI Literacy, and Media Truth

- Gamification and Motivation Design

- Character, Morality, and Community Leadership

- Health, Energy, and the Human Operating System

- Purpose, Identity, and Life Navigation

This is not “extra.” This is what school should have been teaching all along, because these are the skills that keep people from falling apart.

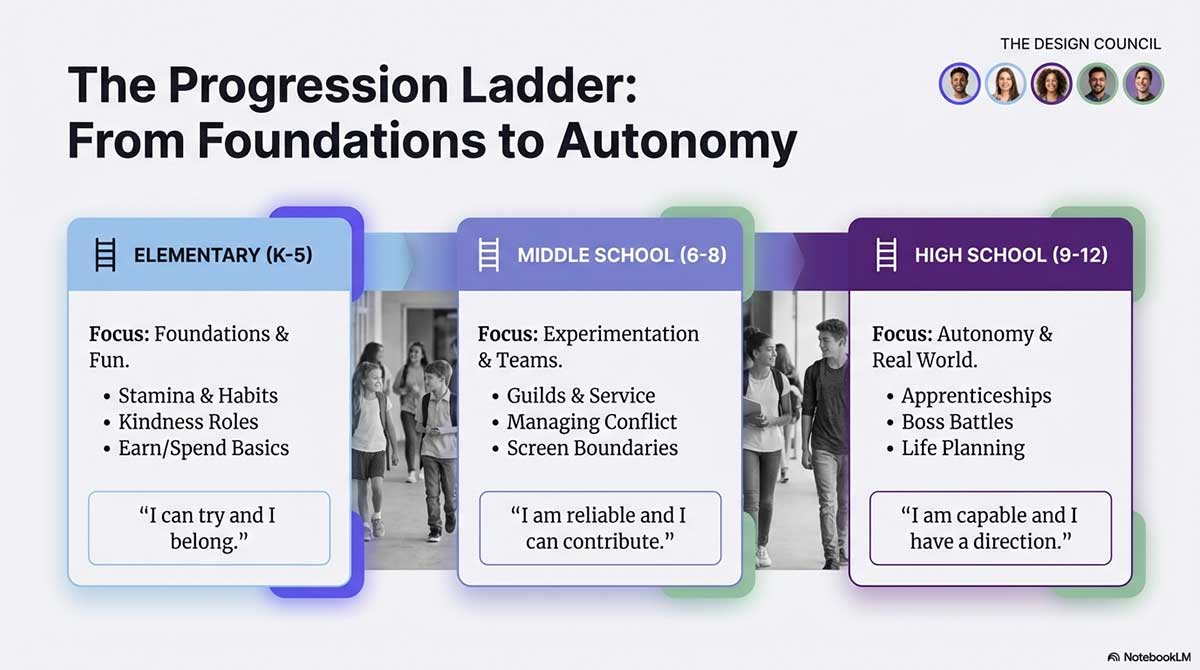

And the structure matters as much as the subjects.

Students level up through skill trees instead of being labeled “smart” or “behind.” They complete weekly Ship Days where they publish, present, build, sell, or serve, so learning ends in pride, not in tests. They earn status through reliability, mastery, and contribution, not cruelty. They build portfolios from elementary through high school so they can see their growth and prove it to the world. They learn by doing, revising, and trying again, not by pretending once for a grade.

This conversation exists so that by the end, we can say clearly what students should be able to do by the end of elementary school, middle school, and high school. We want a system where a child does not quietly fail for years. Where a student who struggles receives support immediately. Where learning feels like progress. Where discipline becomes identity. Where kids actually want to go to school because school finally feels connected to life.

The world changed.

Now education has to change too.

(Note: This is an imaginary conversation, a creative exploration of an idea, and not a real speech or event.)

Topic 1: Literacy and Communication Power

We begin here because literacy is the foundation of everything else. If a young person cannot read with confidence, cannot write clearly, and cannot speak without fear, every other subject collapses. Money, technology, morality, purpose, even mental health all depend on communication.

This is not a “language arts” discussion. This is a discussion about freedom.

The Five Speakers (Design Council)

- Natalie Wexler

- Doug Lemov

- John McWhorter

- Deborah Tannen

- Sal Khan

Natalie Wexler opens with a hard truth: reading failure is not about intelligence or motivation. It is about missing knowledge. Children cannot comprehend what they do not understand, no matter how many “reading strategies” we give them. Literacy improves when students build real knowledge about the world while learning how language works.

Doug Lemov agrees, but sharpens the point. Knowledge alone is not enough. Literacy requires daily, deliberate practice. Fluency drills. Sentence construction. Short writing. Speaking reps. Just like athletics or music, improvement comes from repetition, not inspiration.

John McWhorter reframes grammar. He says grammar is not about correctness or obedience. Grammar is leverage. The student who can control sentences can control outcomes. They can argue, negotiate, persuade, and protect themselves. Literacy is power, and power must be taught explicitly.

Deborah Tannen shifts the focus from text to human interaction. Many students are not failing academically; they are failing conversationally. They misread tone, escalate conflict, and lose opportunities because no one taught them how to listen, clarify, disagree, and repair. Conversation is a life skill, not a personality trait.

Sal Khan grounds the conversation in systems. He warns that schools quietly pass students forward with gaps that later turn into shame. A mastery-based system must catch failure early, fix it immediately, and never allow a child to believe they are “bad at learning.”

The group aligns around three critical questions.

Critical Question 1

How do we make every child a confident reader without shame, tracking, or permanent labels?

Natalie Wexler proposes a dual-track model starting in early elementary school. On one track, students learn phonics, decoding, and fluency. On the other, they build knowledge through science, history, and rich content. Reading comprehension improves because students actually understand what they are reading.

Doug Lemov insists that reading must feel safe. That comes from reps. Short, frequent, low-pressure reading practice every day. No public humiliation. No surprise cold-calling meant to catch kids failing. Confidence is built through familiarity.

Sal Khan adds the structural safeguard. Every two weeks, mastery checks identify gaps. If a student is behind, they receive immediate targeted practice. Advancement is based on competence, not calendar time.

Deborah Tannen emphasizes emotional safety. If students associate reading with embarrassment, they will avoid it for life. The classroom culture must normalize struggle and treat confusion as part of learning.

John McWhorter closes the loop. Precision creates confidence. Teach students that asking for clarification is a strength. “I don’t understand yet” must be a respected sentence in school.

Critical Question 2

How do we teach writing as real-world power instead of worksheets?

Doug Lemov argues that writing improves through short, daily practice. One paragraph. One clear explanation. One revision. Students learn that good writing is not talent; it is process.

Natalie Wexler adds that writing collapses when students have nothing to say. Knowledge must come first. When students know history, science, and real-world issues, writing becomes meaningful instead of forced.

John McWhorter brings the focus to sentences. Students must learn sentence control before style. Simple sentences. Clear sentences. Then variation. Then persuasion. Control comes before flair.

Deborah Tannen introduces writing under pressure. Students must practice writing when they disagree, when they are upset, and when they want something. This is how adults succeed without burning bridges.

Sal Khan proposes the portfolio rule. Every student keeps a writing portfolio from elementary school onward. Growth is visible. Identity shifts from “I’m bad at writing” to “I’m improving.”

Critical Question 3

How do we build speaking and listening skills so students can think clearly out loud?

Deborah Tannen leads here. Speaking is not about confidence; it is about structure and listening. Students practice summarizing what others say, asking clarifying questions, and disagreeing without attacking.

Doug Lemov emphasizes frequency. Two-minute explanations. Pair shares. Small-group debates. Speaking becomes normal because it happens daily.

John McWhorter insists on clarity over charisma. Students learn to speak in a simple structure: point, reason, example. This alone dramatically improves persuasion.

Natalie Wexler reminds the group that speaking must be grounded in knowledge. Students should speak about real content, not only opinions. Substance builds confidence.

Sal Khan ensures inclusion. Students who fear public speaking begin with recordings, then small groups, then class. Growth is required, but extroversion is not.

Clear Outcomes by Educational Stage

By the end of Elementary School

- Students read grade-level texts with confidence and stamina

- They write clear paragraphs and simple stories

- They speak in small groups and listen respectfully

By the end of Middle School

- Students read nonfiction and explain meaning in their own words

- They write short arguments with evidence and revise them

- They disagree respectfully and speak with structure

By the end of High School

- Students read complex material and learn independently

- They write professional emails, essays, and persuasive proposals

- They present, negotiate, and communicate under pressure

When literacy and communication are designed this way, students do not fall into silence, crime, or confusion. They gain voice. They gain agency. They gain the ability to participate in society instead of rebelling against it blindly.

Topic 2: Money, Economics, and Ethical Earning

If students graduate without understanding money, they do not just lack knowledge. They lack options. When options disappear, desperation grows, and desperation is where bad decisions start to feel reasonable. This subject exists to prevent that.

Money education is not about making kids obsessed with wealth. It is about teaching them how the world works, how to earn ethically, how to avoid traps, and how to build a life where they can contribute with dignity.

The Five Speakers (Design Council)

- Alex Hormozi

- Ramit Sethi

- Beth Kobliner

- Daymond John

- Muhammad Yunus

Beth Kobliner opens by stating that children should not learn money in a single semester in high school. They should build it the same way they build reading: a little at a time, every year, with real-life practice.

Ramit Sethi pushes for automation and behavior. People do not fail financially because they are stupid. They fail because they do not have systems. So students must learn scripts, checklists, and routines that make good money behavior almost automatic.

Alex Hormozi reframes earning. The real skill is not “hustle.” The real skill is value creation. Find a problem, solve it well, communicate clearly, and you will always be able to earn.

Daymond John emphasizes identity and confidence. Students must learn sales without shame. Not manipulation. Sales as service. If you can communicate value, you can open doors for your future.

Muhammad Yunus insists ethics is not optional. A money curriculum without ethics trains predators. A good system trains builders: earn by improving lives, not by extracting from weakness.

Now the group addresses three critical questions.

Critical Question 1

What is the safest age-based path from “earning tokens” to earning real money ethically?

Beth Kobliner proposes a three-stage model.

In elementary school, children earn classroom tokens tied to contribution, responsibility, and teamwork, then practice budgeting those tokens toward goals. This builds habits without risk.

In middle school, students enter a supervised “school marketplace.” They can earn small real amounts through safe services: tutoring younger students, creating posters for clubs, helping with events, basic video editing for school projects. Everything is transparent, adult-supervised, and opt-in.

In high school, students move into internships, apprenticeships, or real client projects with contracts and clear boundaries. They learn how to invoice, how to deliver on time, and how to protect their reputation.

Alex Hormozi adds a rule: students should start with services, not products. Services teach skill, responsibility, and communication faster, with less cost and less risk.

Daymond John agrees and adds brand training. Even a teenager has a brand. Their brand is reliability. Teach them that showing up, being respectful, and doing great work makes them valuable anywhere.

Ramit Sethi pushes for guardrails and systems. No child should be earning without learning budgeting at the same time. Every earning project must include a simple money routine: spend, save, invest, give. Even if investing is simulated at first, the habit starts early.

Muhammad Yunus insists on social contribution baked in. A small portion of earnings should go to something meaningful, chosen by students. Not as forced charity, but as identity training: I earn by helping, and I share because I belong to a community.

Critical Question 2

How do we teach budgeting, pricing, taxes, credit, investing, and scams through projects rather than lectures?

Ramit Sethi proposes a “money operating system” taught through real actions.

Students set up a basic budget in three buckets: spend, save, invest. They practice it weekly. The point is not perfection. The point is routine.

Beth Kobliner introduces the age ladder.

Elementary: needs vs wants, saving for goals, being careful with “easy money.”

Middle: budgeting, comparison shopping, basic banking, scam spotting.

High: taxes, credit, interest, insurance, investing basics.

Alex Hormozi insists pricing must be taught early. Students learn to calculate cost, time, and value. They learn that pricing is not guessing. It is a skill.

Daymond John brings in negotiation and marketing. Students learn how to explain what they do, why it matters, and how to ask without shame. They also learn what honest marketing looks like, and how fake marketing destroys trust.

Muhammad Yunus keeps ethics at the center. Every project includes an “impact check.” Who does this help? Who could it harm? Are we selling something real or selling a fantasy?

Then they agree on a powerful method: every concept is tied to a real project.

Budgeting: manage project money.

Pricing: price a service.

Taxes: simulate a paycheck and deductions, then learn the basics of filing.

Credit: model interest and debt traps.

Investing: start with simulated compounding, then responsible real-world basics later.

Scams: students analyze real scam examples and learn defense scripts.

Critical Question 3

How do we hard-wire ethics so money skills never drift into manipulation or exploitation?

Muhammad Yunus speaks first. He says ethical earning is simple: your success must not require someone else’s harm. If your profit depends on addiction, deception, or despair, it is not success. It is extraction.

Daymond John translates it into street language: do not ruin your name. Your name is worth more than quick money. Students must understand that reputation is a financial asset.

Ramit Sethi adds that ethics must become a checklist, not a lecture. Before any earning project launches, students answer three questions: is it honest, is it fair, is it sustainable? If not, redesign it.

Alex Hormozi reframes sales. Sales is not pressure. Sales is clarity. If you have real value, you do not need tricks. Teach students to communicate benefits plainly and let the customer decide.

Beth Kobliner adds the child safety lens. We must guard against students being exploited by adults or by peers. The system must protect children, even while it teaches earning.

They agree on a final principle: every student must graduate with an ethical code for money, written in their own words, tested against real scenarios.

Clear Outcomes by Educational Stage

By the end of Elementary School

- Students understand saving, spending, and simple budgeting

- They understand needs vs wants and why “easy money” is risky

- They earn through contribution and learn responsibility

By the end of Middle School

- Students can run a small, supervised service project and track money

- They can price a simple service and improve quality through feedback

- They can spot common scams and understand basic banking

By the end of High School

- Students can earn ethically through internships, apprenticeships, or client work

- They understand taxes, credit, interest, investing basics, and financial traps

- They graduate with a portfolio, a money system, and an ethical code

Topic 3: Mindset, Habits, and Emotional Fitness

If Topic 1 gives students a voice, and Topic 2 gives them options, Topic 3 gives them stability. This is the subject that prevents a bad day from becoming a bad life.

A lot of what adults call laziness is really exhaustion, shame, anxiety, or a nervous system that never learned how to calm down. If we do not teach emotional fitness, we leave students defenseless against stress, embarrassment, rejection, and distraction. Then we punish them for the symptoms.

This subject turns inner life into a set of practical skills that can be trained, measured, and improved.

The Five Speakers (Design Council)

- Tony Robbins

- Angela Duckworth

- BJ Fogg

- Carol Dweck

- Kelly McGonigal

Tony Robbins begins with a blunt observation. Students do not fail because of a lack of information. They fail because of a lack of state control. If a student cannot shift out of panic, apathy, rage, or shame, the best curriculum in the world will not reach them.

Angela Duckworth adds that resilience is not inspirational. It is built through practice. The student must learn how to keep going after boredom, frustration, and setbacks. She argues that grit is not a personality trait. It is a habit of finishing.

BJ Fogg insists the system must stop relying on willpower. Most behavior change fails because goals are too big and the start is too hard. Habits must be designed to be easy, tiny, and repeatable. Identity grows from small wins.

Carol Dweck reframes the issue. Students collapse when they believe failure means they are stupid. A growth mindset is not positive thinking. It is the ability to treat effort and feedback as the path to skill.

Kelly McGonigal brings in stress science. Stress is not the enemy. The relationship with stress matters. Students must learn to interpret stress as a signal, not a verdict, and learn tools to recover quickly.

Now they focus on three critical questions.

Critical Question 1

What daily 10 to 15 minute practice measurably improves focus, behavior, and resilience?

BJ Fogg proposes a daily “micro-routine” that is so small it is almost impossible to refuse. The system is consistent: cue, tiny action, immediate celebration. Students do not need motivation to start. They need a start that feels easy.

Tony Robbins says the practice must include a fast state shift. One minute can change everything. He recommends a short routine: posture change, breathing change, focus change. Students learn that they are not trapped in their mood.

Kelly McGonigal adds a nervous system reset. A simple breathing protocol, done daily, trains the body to downshift. The point is not spirituality. The point is physiology.

Angela Duckworth makes it measurable. Students track completion streaks and small progress. The goal is consistency. When students see a streak, identity begins to form.

Carol Dweck insists language must be part of the practice. Students learn to change internal speech from “I can’t” to “I can’t yet.” Not as a slogan, but as a trained reflex. The daily practice includes one reflection sentence: what did I improve today?

They agree on a practical daily routine:

- One minute state shift

- Two minutes nervous system reset

- Five minutes skill reps or focused work sprint

- Two minutes reflection and planning

- One minute appreciation or kindness act

Simple, fast, repeatable.

Critical Question 2

How do we train students to recover from failure, embarrassment, rejection, and setbacks?

Carol Dweck says the school must normalize mistakes as data. Students should redo work regularly. Revision is not a punishment. Revision is the method.

Angela Duckworth introduces “finish training.” Students must complete hard things. Not huge things at first, but slightly challenging things consistently. A student’s confidence grows when they can point to completed work.

Tony Robbins teaches reframing. Students learn to ask, what does this mean, and what do I do next? The problem is not the event. The problem is the meaning they attach to it. Train meaning, train action.

Kelly McGonigal says recovery requires self-compassion. Students who hate themselves do not bounce back. They hide. They lie. They quit. Self-compassion is not softness. It is performance. Students learn to speak to themselves like a coach, not a bully.

BJ Fogg makes it systematic. After a failure, students do a simple three-step reset: make it smaller, make it easier, and restart immediately. Not tomorrow. Today.

They agree on a school-wide rule:

No one is allowed to fail alone.

Every setback triggers a small support process: reflect, revise, retry.

Critical Question 3

How do we make discipline feel empowering and identity-building, not punishment?

Tony Robbins says discipline becomes empowering when the student feels control. Give students tools that work quickly. When they can shift their state and take action, discipline stops feeling like a cage.

BJ Fogg says discipline is built through tiny habits. If students succeed daily, they start to believe they are the kind of person who follows through.

Angela Duckworth says discipline requires long-term purpose. Students need a reason to practice. That reason can be personal, social, or creative, but it must feel real to them.

Carol Dweck insists praise must change. Praise effort, strategy, and improvement. Do not praise fixed traits like “smart.” Trait praise makes students afraid to fail.

Kelly McGonigal adds social design. Students become disciplined when discipline is normal in their tribe. Build classroom culture where it is cool to practice, cool to improve, and cool to keep your word.

They settle on a crucial idea: discipline should earn status. Not status for being talented. Status for being reliable.

Clear Outcomes by Educational Stage

By the end of Elementary School

- Students can name emotions and use simple tools to calm down

- They build small habits and feel pride in consistency

- They learn that mistakes are normal and revision is part of learning

By the end of Middle School

- Students can manage stress and embarrassment without melting down

- They can build habits for reading, focus, and kindness with streak tracking

- They learn to recover from rejection and keep going

By the end of High School

- Students have a personal operating system for focus, health, and discipline

- They can handle failure and pressure without quitting or self-sabotage

- They leave with identity as a capable person who finishes what they start

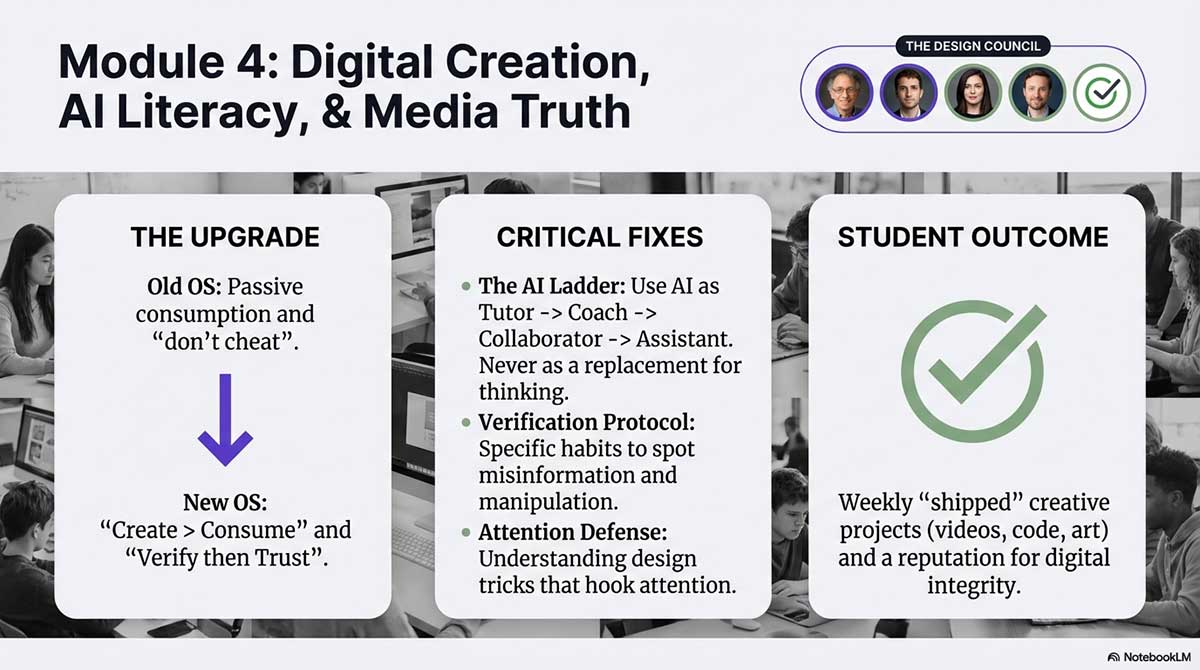

Topic 4: Digital Creation, AI Literacy, and Media Truth

If we do not teach this, the internet will teach it for us. And the internet’s curriculum is simple: consume more, react faster, trust less, and chase attention.

This subject flips the script. Students learn to create more than they consume, verify more than they share, and use AI as a tool without letting it replace their thinking. They learn how influence works so they are harder to manipulate.

The Five Speakers (Design Council)

- Mitchel Resnick

- Tristan Harris

- Renée DiResta

- Ethan Mollick

- Common Sense Media (Representative)

Mitchel Resnick opens with a principle: children should grow up as creators. If students only consume, they become dependent. If they build, remix, and publish, they gain agency. He argues for a studio culture where students make things constantly, not just for grades.

Tristan Harris warns that modern platforms are designed to capture attention, not to develop humans. If a school ignores attention training, it is like training swimmers without teaching them about currents. Students must learn to protect focus and recognize design tricks that pull them into compulsive loops.

Renée DiResta brings the truth problem into focus. Misinformation spreads because it fits emotional instincts. Outrage, fear, tribe loyalty. Students need practical verification skills, plus humility, plus the courage to say, “I do not know yet.”

Ethan Mollick reframes AI as a productivity partner. Used properly, AI can help students draft, brainstorm, critique, and practice. Used poorly, it becomes a shortcut that weakens skill. The school must teach rules for AI that make students stronger, not weaker.

Common Sense Media (Representative) anchors everything in safety and ethics. Students need clear boundaries: privacy, consent, respectful posting, and long-term digital reputation. They should not learn this after damage is done.

Now the group tackles three critical questions.

Critical Question 1

What are the clear rules for AI use in school so it helps learning without becoming cheating or dependency?

Ethan Mollick proposes the “AI Ladder,” a progression that is easy to enforce.

- AI as a tutor: explain concepts, quiz me, give examples

- AI as a coach: review my draft, suggest improvements, highlight gaps

- AI as a collaborator: brainstorm options, compare approaches

- AI as an assistant: formatting, outlines, practice simulations

He draws one bright line: AI must not replace the student’s thinking. The student must still show original reasoning, sources, and revision.

Mitchel Resnick adds that students must build first, then use AI. Create your draft, then use AI to improve it. If you reverse that order, students never build confidence.

Renée DiResta adds verification. If AI makes a claim, students treat it as a lead, not a fact. Students must verify with reliable sources and learn how hallucinations happen.

Tristan Harris adds the attention rule. AI should reduce cognitive load, not increase distraction. Students use AI in structured time blocks, not in endless chat loops.

Common Sense Media (Representative) insists on privacy rules. No uploading personal data, private school documents, or other people’s information. Consent must be trained early.

They agree on a simple classroom statement students can remember:

Use AI to learn, not to pretend.

Critical Question 2

How do we build “create more than consume” habits through publishing and portfolios, without turning school into a shallow influencer contest?

Mitchel Resnick proposes a studio requirement in every grade. Students make things weekly: videos, posters, essays, code projects, podcasts, presentations. Publishing creates pride and identity. Students become producers.

Tristan Harris warns that raw metrics can poison motivation. Likes and views should not become grades. The portfolio should focus on craftsmanship, clarity, and improvement, not popularity.

Common Sense Media (Representative) adds age-appropriate boundaries. In elementary school, publishing is internal to the classroom. In middle school, it can be school-wide. In high school, public publishing is optional and guided.

Ethan Mollick adds a practical tool: the “Creation Loop.”

Plan, create, test, improve, publish, reflect. AI can support each step, but the student must own the loop.

Renée DiResta insists students learn influence with integrity. If they publish, they must learn disclosure, honesty, and the difference between persuasion and manipulation.

They agree on a key rule:

Every student ships work weekly, but the scoreboard is improvement, not fame.

Critical Question 3

How do we make students manipulation-proof against misinformation, outrage, and algorithm-driven tribalism?

Renée DiResta starts with the core skill: slow down the share reflex. Students must learn a simple verification protocol:

- What is the claim?

- Who is the source and what is their incentive?

- What evidence is shown and what is missing?

- Can I confirm this with a second trustworthy source?

- What would change my mind?

Tristan Harris adds design literacy. Students learn how feeds rank content, why outrage spreads, and how notifications train compulsion. Once students see the machine, it loses power.

Common Sense Media (Representative) teaches digital citizenship. Students practice: ask before reposting someone’s image, avoid dogpiling, protect privacy, do not spread humiliation.

Ethan Mollick adds AI-specific risks: deepfakes, fake quotes, and synthetic images. Students learn basic detection habits and the mindset: verify before believing.

Mitchel Resnick closes with empowerment. The best defense against manipulation is creation. When students know how content is made, edited, framed, and optimized, they become less gullible and more thoughtful.

They agree on a school-wide habit:

Pause, verify, then speak.

Clear Outcomes by Educational Stage

By the end of Elementary School

- Students practice safe, kind digital behavior and basic privacy rules

- They build simple creations weekly (posters, slides, short videos, stories)

- They can explain the difference between a fact, an opinion, and a trick

By the end of Middle School

- Students can research, cite sources, and spot common misinformation patterns

- They create a portfolio of digital work and ship weekly projects

- They understand attention traps and can build healthier screen habits

By the end of High School

- Students use AI ethically for learning, drafting, and skill-building with verification habits

- They can run real-world digital projects with measurable outcomes and integrity

- They graduate manipulation-resistant, with a portfolio and a reputation they are proud of

Topic 5: Gamification and Motivation Design

A school can have the best subjects in the world and still fail if students do not feel progress. The current system often rewards compliance, punishes mistakes, and makes learning feel like waiting. Gamification is not about making school childish. It is about making learning feel like a well-designed game: clear goals, visible growth, frequent wins, meaningful challenges, and a culture where effort earns respect.

Done well, gamification reduces dropout, reduces shame, and increases mastery. Done poorly, it becomes points, prizes, and addiction loops. So the design has to be careful.

The Five Speakers (Design Council)

- Jane McGonigal

- Sebastian Deterding

- Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi

- James Clear

- Daniel Pink

Jane McGonigal begins by saying that a good game gives people hope. When students feel hope, they try. When they try, they improve. When they improve, they want to keep going. A school should be a hope machine.

Sebastian Deterding warns that “pointsification” is not gamification. If we just add XP without changing the learning experience, it becomes shallow. The system must reward meaningful behavior: practice, revision, teamwork, and kindness.

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi brings in flow. Students thrive when challenge matches skill. Too easy leads to boredom. Too hard leads to anxiety. The school must adjust difficulty like a great game adjusts levels.

James Clear focuses on habit identity. The best gamification builds identity: I am the kind of person who practices, who finishes, who improves. Streaks and small wins are powerful when they are tied to becoming someone.

Daniel Pink anchors motivation in autonomy, mastery, and purpose. Gamification should not control students. It should empower them to choose paths, master skills, and contribute to something meaningful.

Now they face three critical questions.

Critical Question 1

How do we design XP, quests, and skill trees that boost learning without creating unhealthy addiction loops?

Sebastian Deterding sets the first rule: rewards must be tied to learning actions, not to dopamine tricks. No random loot boxes. No endless scrolling. No variable rewards designed to hook. The school uses clear and predictable progression.

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi says the real reward is flow. The system must help students enter flow by matching tasks to skill level, then gradually raising difficulty. Students do not need constant prizes if the work itself feels meaningful and achievable.

Jane McGonigal proposes the “quest structure.” Every week, students have missions with a beginning, middle, and end. They feel completion. Completion creates healthy satisfaction.

James Clear recommends streaks for behaviors that matter: reading, practice reps, kindness actions, sleep routines. But streaks must be “forgiving.” Missing a day should not reset everything and trigger shame. The rule becomes: never miss twice.

Daniel Pink adds autonomy safeguards. Students should choose quests from a menu. Choice prevents gamification from feeling like manipulation. A game you are forced to play stops being a game.

They agree on a principle:

Progress must be visible, but rewards must stay human.

Critical Question 2

What should be rewarded most, and how do we prevent students from gaming the system?

Daniel Pink insists the top reward is mastery. The system should reward improvement and skill, not speed. If speed becomes the prize, students learn shortcuts and cheating.

Sebastian Deterding proposes a simple hierarchy of what earns the most XP:

- Skill mastery

- Revision and improvement

- Completion and reliability

- Teamwork contribution

- Kindness and repair after conflict

Students can earn points for effort, but badges require proof of skill.

James Clear adds identity rewards. Students should earn status for being reliable and for doing deep work, not for being naturally smart. A culture that respects practice changes behavior.

Jane McGonigal warns that public leaderboards can humiliate. She recommends team-based progress boards and personal progress boards. The student competes mostly with themselves.

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi adds that “gaming the system” often happens when tasks are boring. If tasks are meaningful and well-leveled, cheating drops because students feel engaged and capable.

They agree on a safeguard:

Badges require evidence. XP can be earned daily, but advancement requires performance.

Critical Question 3

How do we structure Ship Day and Boss Battles so every student experiences real wins?

Jane McGonigal introduces Ship Day as the heart of the system. Every week ends with completion. Students publish, present, sell, serve, or demonstrate. They feel the pride of finishing.

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi says Ship Day also creates flow because it gives a clear goal. Students know what they are building toward. Work becomes purposeful.

James Clear suggests making Ship Day a ritual. Same day, same rhythm, same reflection. Ritual builds consistency, and consistency builds identity.

Daniel Pink adds purpose. Ship Day should connect to real people. Students should create something that helps someone, informs someone, or improves the community. Purpose multiplies motivation.

Sebastian Deterding designs Boss Battles as season finales. Every 6 to 9 weeks, students face a larger challenge: a showcase, a debate, a business fair, a community project, a portfolio defense. Boss Battles are not about fear. They are about proving growth.

They agree on three levels of wins:

- Micro wins daily (practice reps)

- Weekly wins (Ship Day)

- Seasonal wins (Boss Battles)

This prevents hopelessness. The student always has a next achievable victory.

Clear Outcomes by Educational Stage

By the end of Elementary School

- Students understand levels, quests, and improvement as a fun normal rhythm

- They build streaks for reading, kindness, and practice reps

- They ship simple work weekly and feel pride in finishing

By the end of Middle School

- Students work in guilds, rotate roles, and earn status through reliability

- They complete weekly Ship Days and learn revision as part of success

- They face seasonal Boss Battles that build confidence, not anxiety

By the end of High School

- Students manage autonomy through choosing quest paths and building portfolios

- They complete public or real-world Boss Battles: pitches, projects, defenses

- They graduate with identity as a capable person who finishes, improves, and contributes

Topic 6: Character, Morality, and Community Leadership

A society does not collapse only because people lack money or skills. It collapses when trust collapses. When students grow up without a practiced moral code, without the ability to repair harm, and without a sense of responsibility to others, everything becomes conflict, cynicism, and chaos.

This subject is not about preaching. It is about training. Morality becomes real when it is practiced through action, community roles, and repair after mistakes. Students learn how to be strong and kind at the same time.

The Five Speakers (Design Council)

- Esther Wojcicki

- Jonathan Haidt

- Greater Good Science Center (Representative)

- Restorative Justice Educator (Representative)

- Dalai Lama

Esther Wojcicki begins with culture. She argues that character forms when a child is trusted with real responsibility. If adults control everything, students never become responsible. A school must give students meaningful jobs, real roles, and real ownership.

Jonathan Haidt frames morality as moral psychology. People do not become ethical through information alone. They become ethical through community norms, identity, and repeated moral action. The school must create a culture where cruelty is low-status and contribution is high-status.

The Greater Good Science Center Representative brings in research. Kindness, gratitude, empathy, and compassion are skills that can be trained. When trained correctly, they reduce aggression and increase resilience. But they must be practiced daily, not taught once.

The Restorative Justice Educator Representative introduces the repair model. Punishment teaches fear and resentment. Repair teaches responsibility. Students must practice how to admit harm, apologize, restore trust, and return to community.

Dalai Lama brings the spiritual without religion. He argues that compassion is not weakness. Compassion is strength. The goal is not to make students passive. The goal is to make them wise enough to reduce harm and strong enough to protect dignity.

Now they focus on three critical questions.

Critical Question 1

How do we teach morality through action, service, responsibility, and repair, not slogans?

Esther Wojcicki proposes daily responsibility roles. Every student has a job: helping younger students, maintaining a classroom system, welcoming newcomers, managing supplies, running a student news board, or supporting events. Morality begins as contribution.

The Greater Good Science Center Representative adds daily micro-practices: gratitude, kindness, noticing others, and simple empathy exercises. Not forced emotional sharing, but daily recognition of humanity.

Jonathan Haidt insists on moral action in real situations. Students should face structured dilemmas: cheating, gossip, exclusion, online shaming. Then they practice what to do, not just what to believe.

The Restorative Justice Educator Representative says action must include repair. When harm happens, students go through a structured repair process: acknowledge, understand impact, apologize, restore, and plan.

Dalai Lama emphasizes motivation. The school should teach students to ask, does this reduce suffering or increase it? That question becomes their compass.

They agree on a key rule:

Every moral lesson must include a practiced behavior, not just a statement.

Critical Question 2

How do we reduce bullying by making status come from contribution and reliability instead of cruelty?

Jonathan Haidt explains that bullying often grows in cultures where status is earned through dominance. The school must redesign status. Make contribution and competence the path to respect.

Esther Wojcicki proposes public recognition for helpfulness and reliability. Not popularity contests, but visible systems that reward students for mentoring, leadership, and finishing.

The Greater Good Science Center Representative adds group identity. Students must belong to something positive: guilds, teams, houses. Belonging reduces the need to dominate.

The Restorative Justice Educator Representative adds immediate intervention with restoration. Bullying is not ignored until it becomes a crisis. The first harm triggers a repair circle. The goal is not humiliation. The goal is accountability and reintegration.

Dalai Lama adds the inner training: students who feel meaningful inside do not need to humiliate others to feel powerful. Self-respect reduces cruelty.

They agree on a design principle:

Cruelty must become low-status, and contribution must become high-status.

Critical Question 3

How do we teach kindness with boundaries so empathy does not become people-pleasing or weakness?

Esther Wojcicki says students must learn self-respect. Kindness without self-respect becomes resentment. Teach students to say no, to ask for help, and to protect their time and safety.

Jonathan Haidt adds moral courage. Sometimes kindness means confronting wrongdoing. Students must learn the difference between harmony and honesty.

The Greater Good Science Center Representative introduces compassion as strength: care for others while also staying grounded. Teach students to notice when they are overwhelmed and to use boundaries.

The Restorative Justice Educator Representative teaches scripts. Students practice phrases for boundaries: stop, I do not like that, I need space, I will report this, I want to repair this. Boundaries must be practiced like any other skill.

Dalai Lama closes with the essence: compassion includes wisdom. Wisdom means knowing what helps and what harms. Kindness is not enabling. Kindness is reducing suffering long-term.

They agree on a final rule:

Kindness must include courage and boundaries.

Clear Outcomes by Educational Stage

By the end of Elementary School

- Students practice kindness daily through roles and service

- They learn apology, honesty, and simple repair after conflicts

- They feel belonging and learn that contribution earns respect

By the end of Middle School

- Students can handle conflict without cruelty and practice restorative repair

- They resist bullying culture and earn status through responsibility

- They learn boundaries and moral courage, not just politeness

By the end of High School

- Students lead community projects and mentor younger students

- They graduate with a personal ethical code tested against real scenarios

- They can repair harm, rebuild trust, and lead with integrity

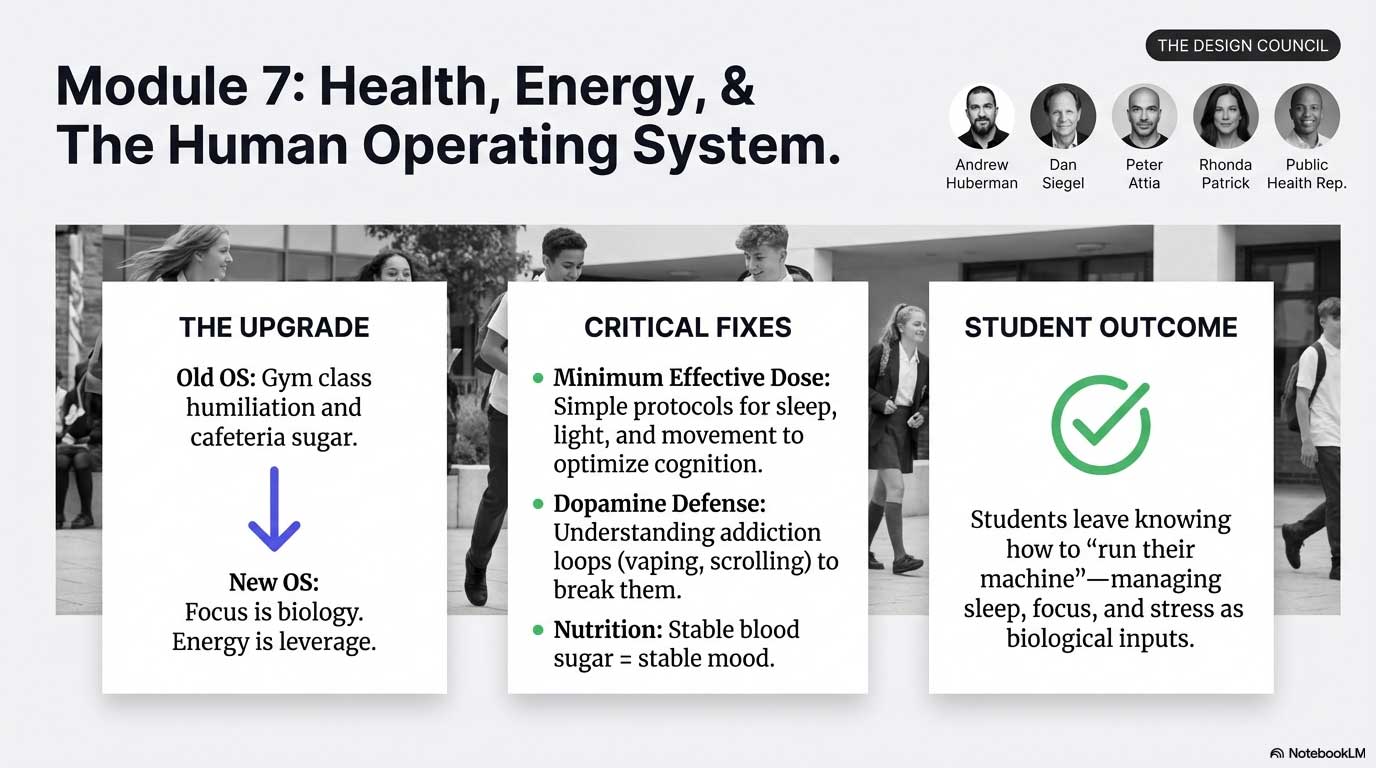

Topic 7: Health, Energy, and the Human Operating System

A student can have a great curriculum and still fail if their body is running on empty. When sleep is broken, food is chaotic, stress is constant, and screens hijack attention, learning becomes harder, emotions become louder, and discipline feels impossible.

This subject is not about turning school into a clinic. It is about giving students a simple operating system for energy, mood, focus, and long-term health, taught in a way that feels practical and empowering, not shameful.

The Five Speakers (Design Council)

- Andrew Huberman

- Dan Siegel

- Peter Attia

- Rhonda Patrick

- Public Health School Leader (Representative)

Andrew Huberman opens with a clean principle: focus is biology. Most students blame themselves for distraction when the real cause is sleep debt, dopamine overload, and inconsistent routines. Teach biology and students gain leverage.

Dan Siegel adds that emotional regulation is a brain skill. Students need to understand what happens in their nervous system during anger, anxiety, and shame. When they can name it, they can manage it.

Peter Attia frames health as long-term freedom. Good health gives students more energy, better mood, and better decisions. Poor health shrinks options, increases medical costs, and increases dependence. Health is a financial and life advantage.

Rhonda Patrick emphasizes nutrition literacy without diet culture. Students need simple principles: protein, fiber, micronutrients, hydration. They should learn to read labels and understand what affects mood and energy.

The Public Health School Leader Representative insists on implementation. Schools must make the healthy choice easy. If the school schedule destroys sleep and cafeteria food spikes sugar crashes, then the lessons become hypocrisy.

Now the group addresses three critical questions.

Critical Question 1

What are the minimum effective habits for sleep, nutrition, movement, and stress control at each age level?

Andrew Huberman proposes a “minimum effective dose” model. Schools should teach a few habits that deliver huge returns, not a long list that students will ignore.

Elementary: consistent bedtime routines, outdoor light, daily movement, hydration.

Middle: sleep timing, caffeine awareness, phone boundaries, daily exercise for mood.

High: deep sleep protection, strength training basics, nutrition routines, stress recovery.

Rhonda Patrick adds a simple nutrition framework students can remember: protein first, fiber often, water always, sugar is occasional. The goal is energy stability, not dieting.

Peter Attia focuses on movement. Students should learn strength and endurance as lifelong habits, not as gym class humiliation. Strength is confidence, and fitness protects the brain.

Dan Siegel adds daily nervous system practices: breathing, body scans, naming emotions, and short resets. The goal is not meditation as religion. It is regulation as skill.

The Public Health Leader Representative demands structural changes: school schedules that respect sleep, active breaks, healthier food defaults, and stress-friendly environments.

They agree on a rule:

Teach fewer habits, practice them daily, measure them simply.

Critical Question 2

How do we teach addiction defense for nicotine, vaping, doomscrolling, gambling loops, and pornography without moral panic or shame?

Dan Siegel begins by explaining that shame fuels addiction. If schools use fear and shame, students hide. The goal must be honesty and skill: how to handle urges, how to break loops, how to ask for help.

Andrew Huberman introduces the dopamine lens. Students must understand why certain behaviors feel irresistible. Not as an excuse, but as a map. If they understand the reward loop, they can interrupt it.

Peter Attia ties addiction to long-term cost. Addiction is not only moral harm. It is a health and financial trap. It steals energy, increases anxiety, and reduces future options.

Rhonda Patrick adds nutrition and sleep as hidden drivers. Many compulsions spike when sleep is low and blood sugar is unstable. Fix the body and willpower becomes easier.

The Public Health Leader Representative adds policy: restrict access where possible, educate early, provide counseling, and build peer-support systems.

They agree on a student-friendly defense strategy:

Notice, delay, replace, repair.

Notice the urge, delay for a short window, replace with a healthier action, repair if you slipped.

Critical Question 3

How do we connect energy management to learning, money, relationships, and performance outcomes?

Peter Attia says students need to see the direct trade: energy creates options. Better energy means better grades, better work, better emotional control, and better earning ability.

Andrew Huberman suggests linking focus training to academic results. Students track how sleep and screen behavior affects their ability to learn. The goal is self-discovery, not punishment.

Dan Siegel connects health to relationships. A regulated nervous system reduces conflict and increases empathy. Students learn that calm is not just comfort. Calm is social success.

Rhonda Patrick links food to mood. Students learn that stable nutrition reduces irritability and anxiety. That improves friendships, family relationships, and classroom behavior.

The Public Health Leader Representative insists on real-world tasks: students build a personal “energy plan” and test it during exam weeks, sports seasons, or major projects.

They agree on a final outcome:

Students leave school knowing how to run their body so their life does not run them.

Clear Outcomes by Educational Stage

By the end of Elementary School

- Students understand sleep, food, water, and movement as energy tools

- They can calm themselves with simple breathing and body awareness

- They build basic habits that support learning and kindness

By the end of Middle School

- Students understand dopamine loops and attention traps

- They build healthier phone boundaries and stress recovery routines

- They can use movement, sleep, and nutrition to stabilize mood and focus

By the end of High School

- Students graduate with a personal health operating system that works

- They understand addiction defense and know how to seek help without shame

- They connect energy habits to money, learning, relationships, and performance

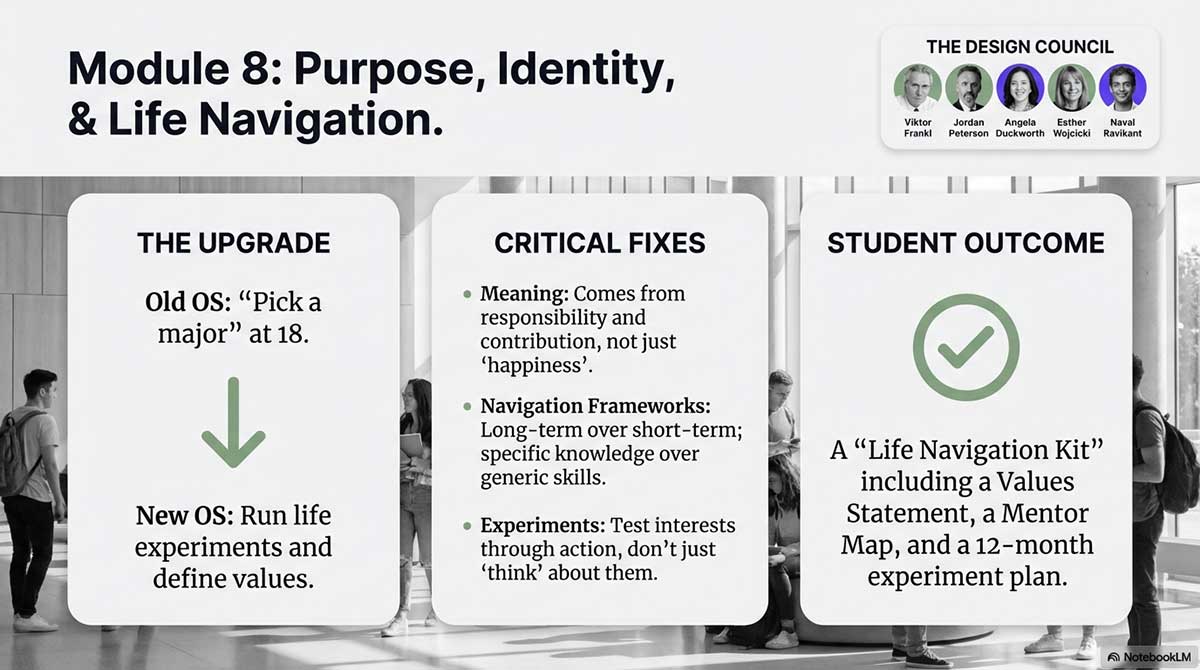

Topic 8: Purpose, Identity, and Life Navigation

If students learn to read, earn, regulate, create, and lead, but still do not know who they are becoming, they can drift into emptiness. Skills without direction often turns into anxiety, imitation, or chasing status. This subject exists so students graduate with a compass, not just tools.

Purpose is not something we hand to kids. It is something we help them discover through action, reflection, and contribution.

The Five Speakers (Design Council)

- Viktor Frankl

- Jordan Peterson

- Angela Duckworth

- Esther Wojcicki

- Naval Ravikant

Viktor Frankl opens by grounding the entire subject in one idea: meaning is not comfort. Meaning is responsibility. A young person becomes stable when they feel needed, when their life is connected to something beyond mood.

Jordan Peterson takes it to structure. He argues that direction is built through order: tell the truth, clean up your responsibilities, and aim at something worthwhile. Most teenagers are not lazy. They are overwhelmed and unclear.

Angela Duckworth brings it to practice. Identity becomes real through what you repeatedly do. Confidence is a side effect of kept promises. Purpose becomes believable when it is matched by consistent effort.

Esther Wojcicki insists the school must treat students as capable. Trust creates growth. When young people are trusted with real ownership and real responsibility, they discover who they are.

Naval Ravikant adds calm realism. Many students feel pressured to pick one destiny too early. He argues the system should teach decision-making frameworks, long-term thinking, and the ability to run experiments in life without panic.

Now the group aligns around three critical questions.

Critical Question 1

How do we teach meaning and purpose without forcing one ideology?

Viktor Frankl proposes a simple approach: purpose comes from three sources. Contribution (what you give), love (who you care for), and courage (how you face suffering). The school does not need to preach a worldview. It needs to help students practice these three areas.

Jordan Peterson agrees but warns against vagueness. If purpose is only “be happy,” it collapses under stress. Purpose must be connected to responsibility: something you commit to even when you do not feel like it.

Esther Wojcicki says purpose must be experienced, not explained. Give students roles that matter, projects that help real people, and the chance to lead. Purpose emerges from doing.

Angela Duckworth adds that purpose needs a long runway. Many kids will not find a “calling” at 14. The goal is not to force a final answer. The goal is to build a habit of aiming, practicing, and adjusting.

Naval Ravikant suggests teaching purpose as “alignment.” What do you enjoy improving? What can you become good at? What helps other people? Where do those overlap? That creates direction without ideology.

Critical Question 2

How do we prevent identity confusion from turning into anxiety, nihilism, or drifting?

Jordan Peterson says confusion becomes dangerous when life is unstructured. He proposes that students learn a few non-negotiables: sleep, basic order, honesty, and responsibility. When those are stable, anxiety drops and clarity rises.

Viktor Frankl adds that emptiness grows when people feel unnecessary. The school must make every student needed. Even struggling students must have a role where others depend on them.

Angela Duckworth introduces identity through commitment. Students build self-trust by finishing small things consistently. A student who finishes becomes harder to manipulate and less likely to collapse into shame.

Esther Wojcicki emphasizes trust and independence. Over-control produces fragile kids who fear life. Give autonomy in safe doses, and identity strengthens through real decisions.

Naval Ravikant recommends teaching “detachment from the crowd.” Students learn to notice social pressure, step back, and choose deliberately. A student who can pause is a student who can steer.

They agree on a practical school rule:

Every student runs life experiments, but nobody is allowed to drift without support.

Critical Question 3

What decision-making frameworks should every student graduate with for choosing friends, mentors, work, and long-term goals?

Naval Ravikant proposes teaching a few simple frameworks that work everywhere:

- Long-term over short-term

- Compounding habits over intensity

- Specific knowledge and leverage

- Choose environments that support your values

Jordan Peterson adds moral clarity: tell the truth, keep your word, do not lie to yourself. Most bad paths begin with small self-deceptions.

Viktor Frankl adds meaning checks:

- Does this choice reduce suffering for me and others long-term?

- Does it build dignity?

- Would I respect myself after doing it?

Angela Duckworth adds the practice framework:

- Pick one thing to practice seriously for a season

- Measure progress weekly

- Adjust based on results, not feelings

Esther Wojcicki adds the people framework:

- Choose friends who make you stronger, kinder, and more honest

- Choose mentors who challenge you and respect you

- Learn to leave environments that reward cruelty or laziness

They agree that students should graduate with a personal “Life Navigation Kit” that includes:

- a values statement

- a decision checklist

- a mentor map

- a 12-month experiment plan

- a personal code (ethics, health, money, relationships)

Clear Outcomes by Educational Stage

By the end of Elementary School

- Students can name values (honesty, kindness, courage, curiosity) and practice them daily

- They can set simple goals, keep small promises, and reflect on improvement

- They feel needed through classroom roles and service

By the end of Middle School

- Students can handle peer pressure with scripts and boundaries

- They build identity through skill experiments and consistent habits

- They can describe what they are good at, what they are practicing, and why it matters

By the end of High School

- Students graduate with a life plan: health, money, learning, relationships, and contribution

- They can choose mentors, avoid toxic circles, and make decisions under pressure

- They can explain their purpose as a direction they are testing through real action, not a slogan

Topic 9: Short System Recap

Below is the one-page clarity sheet. This is what a student should reliably be able to do by the end of each stage, across all 8 subjects.

By the end of Elementary School (K–5)

1) Literacy and Communication Power

Read grade-level text with confidence and daily stamina

Write clear paragraphs and simple stories

Speak in small groups and listen respectfully

2) Money, Economics, and Ethical Earning

Understand earn, spend, save, give

Practice simple budgeting with tokens or classroom currency

Learn needs vs wants and why “easy money” is risky

3) Mindset, Habits, and Emotional Fitness

Name emotions and use simple calm-down tools

Build small daily habits and feel pride in consistency

Treat mistakes as part of learning and try again

4) Digital Creation, AI Literacy, and Media Truth

Practice safe and kind online behavior

Create simple projects weekly (posters, slides, short videos)

Know the difference between fact, opinion, and trick

5) Gamification and Motivation Design

Understand levels, quests, and progress as normal learning

Build simple streaks (reading, practice, kindness)

Ship something weekly and feel pride in finishing

6) Character, Morality, and Community Leadership

Practice kindness through roles and helpful actions

Learn apology and repair after conflict

Feel belonging and learn that contribution earns respect

7) Health, Energy, and Human Operating System

Learn sleep, water, food, and movement as energy tools

Use basic breathing and body awareness to calm down

Build routines that support learning and behavior

8) Purpose, Identity, and Life Navigation

Identify core values (honesty, kindness, courage, curiosity)

Set small goals and keep simple promises

Feel needed through meaningful classroom roles

By the end of Middle School (6–8)

1) Literacy and Communication Power

Read nonfiction and explain meaning in their own words

Write short arguments with evidence and revise them

Disagree respectfully and speak with structure

2) Money, Economics, and Ethical Earning

Run a small supervised service project and track money

Price a simple service and improve through feedback

Understand basic banking and scam defense

3) Mindset, Habits, and Emotional Fitness

Recover from embarrassment and rejection without melting down

Build focus and habit streaks with simple tracking

Use stress tools and finish challenging work

4) Digital Creation, AI Literacy, and Media Truth

Research, verify sources, and cite responsibly

Create weekly portfolio work and publish safely

Understand attention traps and build healthier screen habits

5) Gamification and Motivation Design

Work in teams or guilds and rotate responsibility roles

Use Ship Day to finish and improve work weekly

Face seasonal challenges that build confidence

6) Character, Morality, and Community Leadership

Use restorative repair to handle conflicts

Resist bullying culture and build status through reliability

Practice kindness with boundaries, not people-pleasing

7) Health, Energy, and Human Operating System

Understand dopamine loops and attention hijacking

Build better phone, sleep, and stress routines

Use movement and nutrition to stabilize mood and focus

8) Purpose, Identity, and Life Navigation

Handle peer pressure with scripts and boundaries

Discover strengths through skill experiments

Explain what they are practicing and why it matters

By the end of High School (9–12)

1) Literacy and Communication Power

Read complex material and learn independently

Write professional emails, essays, and persuasive proposals

Present, negotiate, and communicate under pressure

2) Money, Economics, and Ethical Earning

Earn ethically through internships, apprenticeships, or real client work

Understand taxes, credit, interest, investing basics, and traps

Graduate with a money system and a personal ethics code

3) Mindset, Habits, and Emotional Fitness

Maintain a personal focus and discipline system that works

Handle failure and pressure without quitting or self-sabotage

Finish long projects and build strong self-trust

4) Digital Creation, AI Literacy, and Media Truth

Use AI ethically to learn, draft, and improve with verification habits

Build a real portfolio with measurable outcomes

Stay manipulation-resistant and reputation-aware

5) Gamification and Motivation Design

Choose quest paths, manage autonomy, and level up skills intentionally

Complete major “Boss Battle” projects and defend their portfolio

Earn status through reliability, mastery, and contribution

6) Character, Morality, and Community Leadership

Lead community projects and mentor younger students

Repair harm, rebuild trust, and act with integrity

Graduate as someone people can rely on

7) Health, Energy, and Human Operating System

Graduate with a health routine that supports performance

Understand addiction defense and know how to seek help without shame

Connect energy habits to learning, relationships, and earning

8) Purpose, Identity, and Life Navigation

Graduate with a life plan: health, money, learning, relationships, contribution

Choose mentors and avoid toxic circles with clarity

Use decision frameworks and a 12-month experiment plan to stay on track

Final Thoughts by Nick Sasaki

What we just built is not a school reform. It is a responsibility reform.

Because if we are honest, the chaos we see is not mysterious. When teenagers cannot read, when they cannot control their emotions, when they cannot imagine a future, when they chase quick status or quick money in destructive ways, that is not a sudden youth problem. That is a predictable outcome of an adult-designed system that stopped teaching the skills life actually requires.

This new system does not ask young people to magically “care more.” It gives them reasons to care. It gives them progress they can see, wins they can feel, and skills they can use immediately, even while they are still in school. It replaces vague lectures with daily practice. It replaces shame with mastery. It replaces boredom with creation. It replaces drifting with direction.

And the real breakthrough is this: we stop treating education as information transfer, and we start treating it as human development.

By the end of elementary school, a child should feel capable. Not perfect, capable. They can read, speak, and finish small tasks. They understand money in simple terms. They know how to calm down. They have a role in their community and feel needed.

By the end of middle school, a student should feel steady. They can read nonfiction, argue respectfully, verify information, resist manipulation, manage embarrassment, and begin earning in safe ways. They are building identity through experiments, not through labels. They are learning that status is earned through contribution, not cruelty.

By the end of high school, a young adult should be ready. Not just academically, ready for life. They can learn independently. They can communicate under pressure. They can earn ethically. They can use technology and AI without losing their mind. They can protect their health and attention. They can lead, repair, and be trusted. They graduate with a portfolio, a money system, a moral code, and a life navigation kit.

That is what school should do.

And yes, this is a big redesign. But it is not fantasy. Everything we described already exists in pieces across the world. The only reason it is not normal is because adults keep accepting a system that was built for a different era, then acting surprised when it produces broken outcomes.

So the final message is simple.

If we want a safer society, we build students who have options.

If we want less crime, we build competence and belonging.

If we want less despair, we build meaning and responsibility.

If we want less manipulation, we teach media truth and attention control.

If we want a generation that can carry the future, we give them a school worth showing up for.

Teenagers are not the problem.

They are the mirror.

And what we just outlined is the kind of education that finally deserves them.

Short Bios:

Natalie Wexler education writer focused on how reading comprehension grows through background knowledge and content-rich curriculum design.

Doug Lemov educator and author known for practical classroom techniques and high-rep routines that reliably raise literacy and student performance.

John McWhorter linguist and writer who explains language clearly and argues for teaching grammar and clarity as real-world power.

Deborah Tannen linguist and communication scholar known for analyzing how conversation, tone, and miscommunication shape conflict and relationships.

Sal Khan founder of Khan Academy, a major voice in mastery-based learning and scalable systems that prevent students from quietly falling behind.

Alex Hormozi entrepreneur and investor known for value creation, offers, and practical business skill-building grounded in execution.

Ramit Sethi personal finance educator known for simple money systems, behavior-first financial habits, and practical frameworks people actually follow.

Beth Kobliner personal finance author and advocate for teaching kids and teens money skills early in clear, age-appropriate ways.

Daymond John entrepreneur and branding expert who emphasizes practical selling, confidence, and building a strong reputation through real value.

Muhammad Yunus economist and social enterprise pioneer known for microfinance and ethical business models centered on human dignity.

Tony Robbins performance and mindset teacher known for state control, motivation, and practical frameworks for building momentum.

Angela Duckworth psychologist known for research on grit, perseverance, and how sustained effort and purpose drive long-term success.

BJ Fogg behavior scientist known for Tiny Habits and designing behavior change through small, repeatable actions rather than willpower.

Carol Dweck psychologist known for growth mindset research and how beliefs about learning shape resilience and achievement.

Kelly McGonigal psychologist and author known for stress resilience and practical methods to turn pressure into performance.

Mitchel Resnick learning researcher known for creative learning and helping students become makers through project-based, playful creation.

Tristan Harris technology ethics advocate known for explaining how attention systems shape behavior and how to design healthier digital habits.

Renée DiResta researcher known for explaining misinformation, online influence systems, and how narratives spread through networks.

Ethan Mollick professor and author known for practical, realistic guidance on using AI for learning and work without losing human judgment.

Common Sense Media representative digital citizenship and youth safety educator focused on age-appropriate media literacy, privacy, and online wellbeing.

Jane McGonigal game designer and author known for using game mechanics to build motivation, resilience, and hopeful progress.

Sebastian Deterding researcher known for ethical gamification design and the difference between meaningful learning games and shallow points systems.

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi psychologist known for Flow theory and how the right challenge-skill balance creates deep engagement.

James Clear author known for habit formation frameworks and building identity through consistent small wins.

Daniel Pink author known for motivation research centered on autonomy, mastery, and purpose as the drivers of meaningful work.

Esther Wojcicki educator known for building student capability through trust, independence, responsibility, and strong school culture.

Jonathan Haidt social psychologist known for moral psychology and how community norms and belonging shape behavior and character.

Greater Good Science Center representative researcher-educator focused on evidence-based practices for kindness, empathy, gratitude, and prosocial behavior.

Restorative justice educator representative school practitioner focused on repair-based discipline, accountability, and reintegration through structured dialogue.

Dalai Lama global teacher of compassion ethics, emphasizing inner strength, responsibility, and reducing harm through wise kindness.

Andrew Huberman neuroscientist known for translating brain and body science into practical tools for focus, sleep, and stress regulation.

Dan Siegel psychiatrist known for teaching emotional regulation and brain-based frameworks that help students name and manage inner states.

Peter Attia physician known for long-term health strategy, prevention, and connecting health habits to performance and life outcomes.

Rhonda Patrick researcher known for translating nutrition and micronutrient science into practical, actionable health guidance.

Public health school leader representative implementation-focused educator who connects health policy, school environments, and student wellbeing outcomes.

Viktor Frankl psychiatrist and philosopher known for meaning-centered life principles and responsibility as the foundation of resilience.

Jordan Peterson psychologist and author known for responsibility, structure, truthfulness, and building direction through disciplined order.

Naval Ravikant entrepreneur and thinker known for decision-making frameworks, long-term thinking, and building calm, self-directed life strategy.

Nick Sasaki creator and curator of ImaginaryTalks, focused on designing practical, future-ready education systems that combine life skills, ethical earning, mindset training, and gamified learning so students can apply what they learn immediately in real life.

Leave a Reply