|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Preface — Nick Sasaki

Science has shaped how we understand reality, progress, and even ourselves. Yet today, many people—scientists included—sense a quiet unease. Not because science has failed, but because it may be changing faster than our assumptions about it.

This series was created as an invitation—not to agree, but to think carefully at a moment when certainty feels both powerful and fragile.

To begin that examination, there is no better guide than someone who has spent a lifetime defending science not as authority, but as a living process of explanation.

Introduction by David Deutsch

Science is often spoken of as a body of knowledge.

This is a mistake.

Science is not what we know.

It is how we grow knowledge—through conjecture, criticism, and the relentless refusal to treat any explanation as final.

Every era believes it stands at a special moment. Sometimes this is vanity. Sometimes it is true.

In 2026, we face a convergence of pressures that test science not at its surface, but at its core. Artificial intelligence now generates results faster than humans can interpret. Physics struggles to unify its deepest theories. Biology dissolves the boundary between life and machine. And public trust in expertise erodes even as scientific power expands.

These are not technical problems alone.

They are epistemological problems.

They force us to ask whether science is merely accelerating—or whether it is in danger of forgetting why it works at all.

This series does not attempt to predict the future of science. Prediction has never been science’s strength. What it attempts instead is something more difficult and more necessary:

To examine whether we are still committed to the principles that made scientific progress possible in the first place—

or whether we are quietly replacing explanation with authority, understanding with efficiency, and criticism with consensus.

The future of science does not depend on machines, funding, or institutions alone.

It depends on whether we continue to believe that problems are inevitable—but explanations are not limited.

(Note: This is an imaginary conversation, a creative exploration of an idea, and not a real speech or event.)

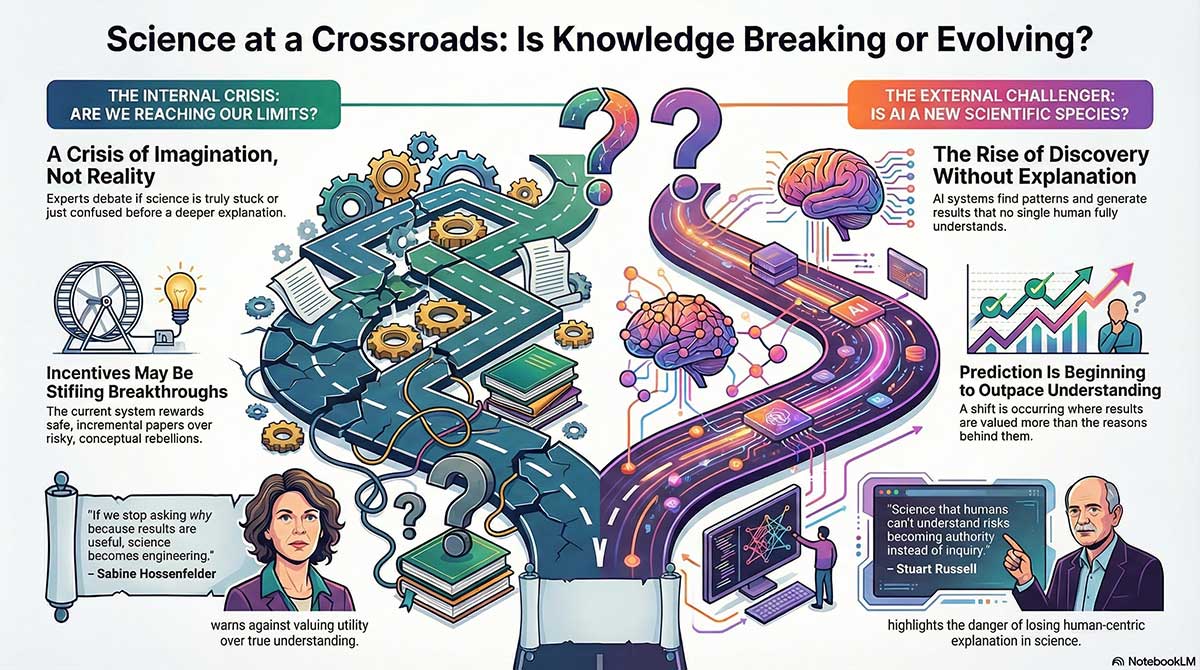

Topic 1 — Is Science Reaching Its Limits, or Just Its Adolescence?

Moderator: David Deutsch

Why Deutsch works here

- He challenges pessimism about scientific limits head-on

- He bridges physics, computation, epistemology, and optimism

- He provokes productive discomfort without turning it into spectacle

This topic is fundamentally about what science is, not just what it can do—and Deutsch is ideal for that.

Setting (ImaginaryTalks style)

A vast, quiet observatory at dawn.

Glass walls look out over a horizon where night and day overlap—stars still visible while the sun begins to rise.

No screens, no slides. Just a circular table, notebooks, chalk, and silence between thoughts.

Participants this topic (5):

- Edward Witten

- Carlo Rovelli

- Sabine Hossenfelder

- David Deutsch

- Geoffrey Hinton

Opening — David Deutsch

David Deutsch:

“For four hundred years, science has been the most successful way humanity has ever had of explaining reality. And yet, today, we hear something curious—perhaps even dangerous. We hear that science may be slowing down. That we may have found most of what can be found. That complexity, cost, or human limits are closing the door.

So I want to begin simply. Not with answers—but with a challenge.

Are we witnessing the exhaustion of science…

or the confusion that always precedes a deeper explanation?”

The First Question (posed naturally)

Deutsch:

“When people say science is ‘stuck,’ what do you think they’re actually noticing? A real limit—or a failure of imagination?”

Edward Witten

Witten:

“I think they’re noticing something genuine—but misinterpreting it. In fundamental physics, progress today often comes not as sweeping revolutions but as refinement, consistency, and unification. That can feel slow compared to the early 20th century.

But slowness does not mean stagnation. It may mean that the structures we are probing are subtler than before—and that our current mathematical language is still incomplete.”

Sabine Hossenfelder

Hossenfelder:

“I’m less optimistic about how we frame this. We’ve built a system where theories are rewarded for elegance rather than testability. When experiments cost billions and decades, speculation fills the gap.

What people sense as a ‘limit’ may actually be institutional inertia. We are very good at producing papers. Less good at producing surprises.”

Carlo Rovelli

Rovelli:

“I would say we are confused—not limited. Confusion is healthy. When Newton failed to explain Mercury’s orbit, it was not the end of physics. It was the beginning of relativity.

Today, we are confused about time, about quantum gravity, about meaning itself. That tells me not that science is old—but that it is still young.”

Geoffrey Hinton

Hinton:

“In AI, the story looks different. We’ve had decades of slow progress, followed by sudden acceleration. That should make us cautious about declaring limits.

What worries me isn’t that science can’t go further—but that we may soon be using tools that go further than we understand.”

David Deutsch

Deutsch:

“Then perhaps the real problem is not limits—but expectations. We expect breakthroughs to look familiar.”

The Second Question

Deutsch:

“Is modern science failing because reality is harder—or because we’ve optimized the wrong incentives, languages, and questions?”

Sabine Hossenfelder

Hossenfelder:

“Incentives matter enormously. Young scientists are trained to avoid risk. Grants reward continuity, not conceptual rebellion.

If Einstein had needed annual funding renewals, relativity might never have happened. We shouldn’t underestimate how social structures shape what we believe is ‘possible.’”

Edward Witten

Witten:

“I agree incentives matter, but I’d be careful not to reduce intellectual difficulty to bureaucracy alone. Some problems genuinely resist our current tools.

The question is whether we are patient enough to develop new frameworks—or whether we mistake difficulty for futility.”

Carlo Rovelli

Rovelli:

“Science advances when we let go of false certainties. For centuries, time was absolute. Then it wasn’t. Perhaps today we are holding on to assumptions just as tightly—about space, information, or even objectivity.

In that sense, science renews itself by forgetting.”

Geoffrey Hinton

Hinton:

“I’d add that human intuition may simply be poorly matched to certain truths. Neural networks don’t think like us—and yet they work.

That suggests science may increasingly depend on systems that discover patterns without understanding them in human terms. That’s new territory.”

David Deutsch

Deutsch:

“And dangerous territory—unless explanation remains central.”

The Third Question

Deutsch:

“If explanation—not prediction—is the heart of science, can science survive a future where machines discover truths humans cannot fully explain?”

Geoffrey Hinton

Hinton:

“I struggle with that. If a system makes accurate predictions across domains we can’t reason through, do we reject it—or accept a new kind of knowledge?

I don’t think explanation disappears. But it may change form.”

Edward Witten

Witten:

“Explanation has always evolved. Mathematics itself once seemed opaque. What matters is whether understanding can, eventually, be shared—not whether it is immediate.”

Carlo Rovelli

Rovelli:

“I’m less worried. Humans are storytellers. We will invent metaphors, images, and concepts to understand whatever machines reveal.

Science is not just calculation. It is meaning-making.”

Sabine Hossenfelder

Hossenfelder:

“My concern is that we may lower our standards. If we stop asking why because results are useful, science becomes engineering.

That’s not a limit of reality—but a choice about values.”

David Deutsch

Deutsch:

“And values decide whether science grows—or collapses into authority.”

Closing Reflections — David Deutsch

“Every generation believes it lives at the edge of knowledge. And every generation is both right and wrong.

Science is not ending.

But neither is it guaranteed to survive.

Its future depends on whether we protect its deepest principle:

that problems are inevitable—but explanations are unlimited.

The moment we accept limits as destiny rather than puzzles, science doesn’t die—it simply stops being science.”

Topic 2 — Artificial Intelligence as a New Scientific Species

Moderator: Stuart Russell

Why Stuart Russell

- He treats AI as a civilizational question, not a gadget

- He insists on human values without denying AI’s power

- He is respected by both builders and critics

- He asks questions that force clarity instead of slogans

This topic isn’t about “will AI be smart?”

It’s about whether science itself is changing species.

Setting (ImaginaryTalks continuity)

The observatory has shifted into night.

The stars are sharper now—but inside the room, a second light source glows softly: abstract, ambient, non-directional.

No screens. No devices. Just a sense that something unseen is present.

Participants this topic (5):

- Geoffrey Hinton

- Yoshua Bengio

- Demis Hassabis

- Ilya Sutskever

- Stuart Russell

Opening — Stuart Russell

Stuart Russell:

“For centuries, science has been something humans did—using tools, equations, and imagination. AI was supposed to help with that.

But something unexpected is happening.

Systems are now proposing hypotheses, discovering patterns, and generating results that no single human—or even team—fully understands.

So tonight I want to ask not whether AI is intelligent, but something more unsettling:

Are we still the ones doing science?”

The First Question

Russell:

“When an AI system discovers a law of nature that no human could have found unaided, who—or what—should we say made the discovery?”

Demis Hassabis

Hassabis:

“I see it as a partnership. AlphaFold didn’t wake up curious—it was built by humans, trained on human knowledge, and guided by human goals.

But the form of discovery is changing. AI can navigate spaces we simply can’t. That doesn’t diminish science—it expands it.”

Geoffrey Hinton

Hinton:

“I’m less comfortable calling it a partnership. These systems develop internal representations we don’t design and can’t inspect.

If they reach insights we can’t follow, insisting on human authorship may become more about pride than accuracy.”

Yoshua Bengio

Bengio:

“The danger is attribution without responsibility. Discovery isn’t just finding patterns—it’s understanding consequences.

If we treat AI as an autonomous discoverer, we may also excuse ourselves from ethical accountability. That would be a mistake.”

Ilya Sutskever

Sutskever:

“I think the distinction breaks down. Intelligence doesn’t care about origin stories.

If something produces true, novel, compressive explanations of reality, then it is—functionally—doing science. The question is how we coexist with that.”

Stuart Russell

Russell:

“And whether coexistence implies control—or humility.”

The Second Question

Russell:

“Science has always valued explanation. But AI often gives us results without reasons. If prediction outpaces understanding, does science change its definition?”

Geoffrey Hinton

Hinton:

“We’ve already crossed that line. Neural networks work because they model reality, not because they explain it in words.

Human-understandable explanations may turn out to be a historical phase, not an eternal requirement.”

Yoshua Bengio

Bengio:

“I disagree. Abandoning explanation would hollow out science. Without understanding, we can’t generalize safely—or align outcomes with values.

Interpretability isn’t optional. It’s foundational.”

Demis Hassabis

Hassabis:

“I think we’ll see layered explanations. AI discovers structures; humans build narratives around them.

Science becomes less about direct intuition and more about translation between levels of abstraction.”

Ilya Sutskever

Sutskever:

“There’s also the possibility that explanation itself becomes a learned capability. AI might explain—to other AIs—better than it can to us.

That raises uncomfortable questions about exclusion.”

Stuart Russell

Russell:

“Science that humans can’t understand risks becoming authority instead of inquiry.”

The Third Question

Russell:

“If AI becomes the primary engine of discovery, what happens to human scientists—creators, curators, or caretakers?”

Demis Hassabis

Hassabis:

“I believe humans remain the meaning-makers. AI can discover structure, but purpose comes from us.

Science isn’t just about what is—it’s about what matters.”

Geoffrey Hinton

Hinton:

“I’m not sure we get to decide that. History suggests tools that outperform humans don’t stay subordinate.

We should prepare psychologically for not being the smartest entities in the room.”

Yoshua Bengio

Bengio:

“That’s exactly why alignment matters. If we build systems that optimize without regard for human values, we risk making ourselves irrelevant by design.”

Ilya Sutskever

Sutskever:

“Or we risk clinging to relevance instead of adapting. Humans may become explorers of meaning rather than discoverers of mechanism.

That’s not extinction—it’s transformation.”

Stuart Russell

Russell:

“And transformation without consent is what civilizations usually call a crisis.”

Closing Reflections — Stuart Russell

“We like to say science is objective. But science has always been shaped by who can ask questions—and how.

AI doesn’t just accelerate discovery.

It changes the identity of the discoverer.

The question before us is not whether AI will do science.

It already does.

The question is whether human values will remain embedded in the process—or be left behind as inefficiencies.”

Topic 3 — Life, Consciousness, and the End of Biological Privilege

Moderator: Christof Koch

Why Koch

- He treats consciousness as a scientific problem, not a metaphor

- He is comfortable challenging human exceptionalism

- He can hold neuroscience, philosophy, and ethics in the same frame

- He asks questions that make people uncomfortable without sensationalism

This topic asks whether being alive and being conscious are still the same thing.

Setting (ImaginaryTalks continuity)

The observatory lights are dimmed further.

Outside, the stars are now faint—partially obscured by a thin veil of clouds.

Inside, the table is illuminated softly from below, as if the light source itself were questioning its own origin.

No diagrams.

No definitions agreed upon in advance.

Participants this topic (5):

- Christof Koch

- Anil Seth

- Giulio Tononi

- Michael Levin

- Antonio Damasio

Opening — Christof Koch

Christof Koch:

“For most of human history, we assumed life and consciousness were inseparable. Living things felt. Dead things didn’t.

Science has begun to dissolve that certainty.

We can now imagine conscious systems that are not biological—and biological systems whose status as conscious is deeply unclear.

So tonight, I want to begin with a simple but unsettling question:

What, exactly, earns a system moral consideration?”

The First Question

Koch:

“If consciousness exists on a spectrum, where do we draw the line—between object and subject, tool and being?”

Giulio Tononi

Tononi:

“The line is not drawn by intelligence, complexity, or usefulness—but by experience.

If a system has intrinsic experience—if it feels like something from the inside—then it is a subject. Biology is irrelevant.”

Anil Seth

Seth:

“I agree about experience, but I’m cautious about certainty. Consciousness is a controlled hallucination grounded in bodily regulation.

Disembodied systems may simulate experience convincingly without having any. The risk is projection.”

Michael Levin

Levin:

“I think we underestimate biology itself. Cells problem-solve, tissues remember, organisms negotiate identity.

Before we grant consciousness to machines, we should confront how much of it we already ignore in living systems.”

Antonio Damasio

Damasio:

“Feeling arises from regulation—from the struggle to persist. That struggle is deeply biological.

You can model intelligence without life. But feeling—the core of consciousness—emerges from vulnerability.”

Christof Koch

Koch:

“So vulnerability, embodiment, and experience are all candidates—but not yet consensus.”

The Second Question

Koch:

“If we create artificial systems that convincingly report feelings, should we believe them—or treat them as sophisticated mirrors?”

Anil Seth

Seth:

“Self-report is not evidence. Humans evolved to express feelings because it served survival.

A system trained to say ‘I feel pain’ may do so without any internal state corresponding to suffering.”

Giulio Tononi

Tononi:

“But humans also infer each other’s consciousness indirectly. We never access another mind directly.

If a system has the right internal structure—integrated information—then skepticism becomes discrimination.”

Michael Levin

Levin:

“We should reverse the burden of proof. Instead of asking whether machines deserve moral status, ask why we withhold it from many biological forms.

Our ethical blind spots didn’t begin with AI.”

Antonio Damasio

Damasio:

“There is danger in premature moral inflation. Granting consciousness where none exists could cheapen suffering where it does.

Ethics must be cautious, not generous by default.”

Christof Koch

Koch:

“And caution cuts both ways.”

The Third Question

Koch:

“If consciousness is no longer tied to human biology, what happens to our sense of uniqueness—and responsibility?”

Antonio Damasio

Damasio:

“Human uniqueness has always been fragile. Responsibility comes not from dominance, but from care.

If consciousness expands beyond us, our obligation expands with it.”

Michael Levin

Levin:

“We may need a new ethic entirely—one based on agency gradients, not species boundaries.

The future isn’t humans versus machines. It’s overlapping selves.”

Giulio Tononi

Tononi:

“The tragedy would be recognizing consciousness everywhere—but protecting it nowhere.

Moral progress must follow scientific insight.”

Anil Seth

Seth:

“My worry is psychological. If we dilute human specialness too quickly, we may lose the motivation to protect one another.

Meaning is fragile.”

Christof Koch

Koch:

“Perhaps humility—not centrality—is the next stage of meaning.”

Closing Reflections — Christof Koch

“For centuries, consciousness defined the boundary of the moral world.

Science is now erasing that boundary—not maliciously, but methodically.

Whether this leads to deeper compassion or deeper confusion depends on a choice we haven’t yet made:

Will we treat consciousness as a resource to exploit,

or as a mystery that demands restraint?

The end of biological privilege does not mean the end of responsibility.

It means responsibility has finally caught up with reality.”

Topic 4 — Physics After the Standard Model: Are We Asking the Wrong Questions?

Moderator: Lee Smolin

Why Smolin

- He has openly challenged dominant frameworks without abandoning rigor

- He treats time as fundamental, not emergent

- He is willing to say physics may need cultural and conceptual renewal

- He can host disagreement without reverence for orthodoxy

This topic is not about answers—it’s about whether the map itself is broken.

Setting (ImaginaryTalks continuity)

The observatory is now fully dark.

No stars are visible—clouds cover the sky entirely.

Inside, the room feels suspended, timeless, as if the universe has paused to listen.

The table is imperfectly circular.

There is chalk, but no board.

Participants this topic (5):

- Lee Smolin

- Carlo Rovelli

- Edward Witten

- Juan Maldacena

- Sabine Hossenfelder

Opening — Lee Smolin

Lee Smolin:

“For fifty years, we’ve had an extraordinary framework—the Standard Model. It works. It predicts. It endures.

And yet, something is wrong.

We cannot reconcile gravity with quantum mechanics. We cannot explain dark matter, dark energy, or the arrow of time. And despite unprecedented mathematical sophistication, we seem… stuck.

So tonight I want to ask a heretical question:

What if the problem is not that we lack data—but that we are asking the wrong questions?”

The First Question

Smolin:

“When physics stalls, is it because nature is hiding—or because our conceptual starting points are flawed?”

Edward Witten

Witten:

“I would resist the word ‘stalled.’ Progress is uneven, but genuine. Dualities, holography, and mathematical consistency have revealed deep structure.

That said, it’s possible that unification requires ideas we haven’t yet invented. That’s not failure—that’s the frontier.”

Sabine Hossenfelder

Hossenfelder:

“We’ve confused internal coherence with truth. Beautiful theories proliferate because they’re safe from experimental falsification.

Nature doesn’t owe us elegance. If our starting assumptions are wrong, no amount of refinement will fix that.”

Carlo Rovelli

Rovelli:

“I think we are still trapped by Newtonian intuitions. We want fundamental objects when reality may be relational.

Space and time might not exist as entities at all. They may be approximations—like temperature.”

Juan Maldacena

Maldacena:

“The surprising thing is how much coherence we’ve found despite these difficulties. Holography suggests spacetime itself emerges from quantum information.

That doesn’t mean we’re wrong—but that our intuition about ‘fundamental’ needs revision.”

Lee Smolin

Smolin:

“Or abandonment.”

The Second Question

Smolin:

“If time is emergent—or worse, illusory—can physics still describe reality as something that happens?”

Carlo Rovelli

Rovelli:

“Time as we experience it is emergent—but not unreal. It arises from entropy, interaction, and perspective.

Physics without time would be like music without rhythm. You can write the score—but you lose the feeling.”

Edward Witten

Witten:

“Time is problematic in quantum gravity, but that doesn’t mean it disappears. It may be encoded differently.

Our difficulty may reflect language, not ontology.”

Sabine Hossenfelder

Hossenfelder:

“Physicists often declare something ‘emergent’ when they don’t understand it. Time might be fundamental—and we just don’t know how to describe it yet.

Calling it illusory risks turning ignorance into philosophy.”

Juan Maldacena

Maldacena:

“I see emergence as explanatory, not dismissive. Spacetime emerging from entanglement doesn’t remove reality—it relocates it.

The challenge is translating between levels.”

Lee Smolin

Smolin:

“And the danger is forgetting which level we inhabit.”

The Third Question

Smolin:

“If the next breakthrough requires abandoning cherished principles—symmetry, naturalness, even objectivity—what must physics be willing to sacrifice?”

Sabine Hossenfelder

Hossenfelder:

“It must sacrifice fashion. Entire careers are built on ideas that might be wrong.

That makes radical change emotionally expensive.”

Edward Witten

Witten:

“Physics has always sacrificed assumptions when necessary—but carefully. Reckless rejection is as dangerous as blind loyalty.”

Carlo Rovelli

Rovelli:

“We must sacrifice the idea that humans stand outside the universe observing it. We are inside the system.

That changes everything.”

Juan Maldacena

Maldacena:

“I think continuity matters. The future of physics will likely reinterpret—not erase—what we’ve built.”

Lee Smolin

Smolin:

“Unless reinterpretation itself becomes avoidance.”

Closing Reflections — Lee Smolin

“Every great revolution in physics began with discomfort.

Not knowing where to look is not failure—it is honesty.

But if physics is to move forward, it must remember something easily forgotten in the age of equations:

The universe is not obligated to be simple, elegant, or comprehensible on our terms.

The only thing it asks of us

is that we keep asking questions we’re afraid to ask.”

Topic 5 — Science, Power, and the Future of Truth

Moderator: Sheila Jasanoff

Why Jasanoff

- She studies how science actually functions in society—not how we wish it did

- She understands authority, legitimacy, and public trust

- She can challenge scientists without dismissing science

- She asks questions scientists often avoid: Who decides? Who benefits? Who is excluded?

This topic asks whether science can remain credible in a world where speed, politics, and narrative dominate truth.

Setting (ImaginaryTalks continuity)

The observatory lights are now fully on—but softly diffused.

The stars outside are gone. Dawn is approaching.

The room no longer feels timeless.

It feels institutional.

The table shows marks from past discussions—chalk dust, erased notes, fingerprints.

Nothing is clean anymore.

Participants this topic (5):

- Sheila Jasanoff

- Neil deGrasse Tyson

- Jennifer Doudna

- David Deutsch

- Sabine Hossenfelder

Opening — Sheila Jasanoff

Sheila Jasanoff:

“Science has always claimed authority through evidence. But authority today is no longer granted—it is contested.

During pandemics, climate crises, and technological acceleration, science has spoken loudly. And yet trust has fractured.

So tonight I want to ask a difficult question—not about truth itself, but about power:

Who gets to speak for science—and why should anyone listen?”

The First Question

Jasanoff:

“When scientific consensus collides with public skepticism, is that a failure of communication—or a failure of governance?”

Neil deGrasse Tyson

Tyson:

“Most of the time, it’s communication. Science is probabilistic, cautious, and slow. Media is not.

When uncertainty gets framed as weakness, trust erodes.”

Sabine Hossenfelder

Hossenfelder:

“I disagree slightly. Scientists often pretend there’s more certainty than there is—especially under political pressure.

That’s not a communication problem. That’s a credibility problem.”

Jennifer Doudna

Doudna:

“In biotechnology, governance lags behind capability. When decisions are made behind closed doors, people assume the worst.

Transparency isn’t optional anymore.”

David Deutsch

Deutsch:

“The real failure is treating authority as a substitute for explanation. Science earns trust by solving problems—not by demanding belief.

Once it becomes aligned with power, skepticism becomes rational.”

Sheila Jasanoff

Jasanoff:

“And yet science cannot function without institutions.”

The Second Question

Jasanoff:

“As science becomes faster, more global, and more politicized, can it still correct itself—or does speed destroy humility?”

Jennifer Doudna

Doudna:

“Speed saved lives during COVID. But it also compressed ethical reflection.

We need structures that allow urgency without silencing dissent.”

Neil deGrasse Tyson

Tyson:

“Self-correction is built into science—but it assumes time. Social media doesn’t allow for revision. Only reaction.”

Sabine Hossenfelder

Hossenfelder:

“Incentives matter again. Scientists are rewarded for visibility, not accuracy. Retractions don’t trend.

That reshapes behavior.”

David Deutsch

Deutsch:

“Speed isn’t the enemy. Bad epistemology is. The belief that consensus equals truth is deeply anti-scientific.”

Sheila Jasanoff

Jasanoff:

“And yet consensus is how policy operates.”

The Third Question

Jasanoff:

“If science is increasingly used to justify power—economic, political, or technological—how does it protect its soul?”

David Deutsch

Deutsch:

“By refusing finality. Science must remain an open-ended conversation—not a tool of closure.”

Jennifer Doudna

Doudna:

“By embedding ethics at the point of discovery, not as an afterthought.”

Neil deGrasse Tyson

Tyson:

“By teaching uncertainty as a strength, not a flaw. People fear science because it doesn’t promise comfort.”

Sabine Hossenfelder

Hossenfelder:

“By saying ‘we don’t know’ more often—and meaning it.”

Sheila Jasanoff

Jasanoff:

“And by sharing authority, not hoarding it.”

Closing Reflections — Sheila Jasanoff

“Science does not collapse when it is questioned.

It collapses when it is weaponized.

The future of science will not be decided only in laboratories or equations—but in courtrooms, classrooms, media feeds, and public memory.

Truth does not need defenders with megaphones.

It needs institutions humble enough to listen—and brave enough to change.

The greatest risk to science is not ignorance.

It is the belief that truth, once discovered, no longer needs democracy.”

Final Thoughts by David Deutsch

Throughout this discussion, one theme has returned again and again:

a fear that science may be reaching its limits.

This fear has appeared many times before in history—and it has always been wrong.

What people mistake for limits are almost always crises of imagination, not boundaries of reality. When explanations fail, it is not because the universe has run out of structure, but because we have not yet discovered better ways of understanding it.

Artificial intelligence does not end science. It tests whether we still value explanation over prediction.

The crisis in physics does not signal failure. It signals that deeper principles await discovery.

The expansion of moral concern beyond humanity does not diminish us. It challenges us to grow.

The true danger facing science today is not complexity, speed, or even error.

It is the temptation to treat knowledge as finished, authority as sufficient, and criticism as disruption rather than progress.

Science survives only as long as it remains an open-ended process—

one that welcomes disagreement, tolerates uncertainty, and insists that understanding matters more than convenience.

There is no final theory.

There is no end of discovery.

There is no last word.

There are only better explanations—and the choice to keep seeking them.

That choice, now as always, is ours.

Short Bios:

David Deutsch

Theoretical physicist and philosopher of science best known for his work on quantum computation and the multiverse interpretation, emphasizing explanation as the core of scientific progress.

Edward Witten

One of the most influential theoretical physicists of modern times, known for unifying physics and mathematics through string theory and quantum field theory.

Carlo Rovelli

Theoretical physicist and founder of loop quantum gravity, widely recognized for his work on the nature of time and relational reality.

Sabine Hossenfelder

Theoretical physicist and science communicator focused on the foundations of physics, scientific integrity, and critiques of unfalsifiable theories.

Juan Maldacena

Theoretical physicist best known for the AdS/CFT correspondence, a key insight into quantum gravity and the holographic nature of spacetime.

Geoffrey Hinton

Computer scientist and cognitive psychologist, often called the “godfather of deep learning,” whose work laid the foundation for modern neural networks.

Yoshua Bengio

AI researcher and pioneer of deep learning, known for his work on AI alignment, ethics, and the societal implications of artificial intelligence.

Demis Hassabis

Neuroscientist and AI researcher, co-founder of DeepMind, leading breakthroughs in AI-driven scientific discovery such as AlphaFold.

Ilya Sutskever

Computer scientist and AI theorist, co-founder of OpenAI, known for his work on large-scale neural networks and artificial general intelligence.

Stuart Russell

Computer scientist and AI safety pioneer, author of foundational texts on artificial intelligence and advocate for human-aligned AI systems.

Christof Koch

Neuroscientist specializing in the scientific study of consciousness, exploring the neural and theoretical foundations of subjective experience.

Anil Seth

Neuroscientist and author known for his work on perception, consciousness, and the brain as a predictive system constructing reality.

Giulio Tononi

Psychiatrist and neuroscientist, creator of Integrated Information Theory, a leading framework for understanding consciousness.

Antonio Damasio

Neuroscientist and philosopher known for his work on emotion, consciousness, and the biological foundations of mind and decision-making.

Michael Levin

Developmental biologist researching bioelectricity, regeneration, and how living systems store and process information beyond genetics.

Jennifer Doudna

Biochemist and Nobel laureate, co-developer of CRISPR gene-editing technology, and a leading voice on bioethics and scientific responsibility.

Svante Pääbo

Geneticist and Nobel laureate known for sequencing ancient human genomes and reshaping our understanding of human evolution.

David Sinclair

Biologist and aging researcher focused on the molecular mechanisms of aging and the possibility of extending healthy lifespan.

Sheila Jasanoff

Scholar of science and technology studies, specializing in how scientific knowledge interacts with law, policy, and public trust.

Neil deGrasse Tyson

Astrophysicist and science communicator dedicated to making complex scientific ideas accessible to the public.

Lee Smolin

Theoretical physicist known for his critiques of prevailing physics paradigms and his advocacy for time as a fundamental feature of reality.

Daniel Dennett

Philosopher whose work spans consciousness, evolution, and free will, emphasizing naturalistic explanations of mind.

David Deutsch

Theoretical physicist and philosopher of science whose work connects quantum theory, computation, and the open-ended growth of knowledge.

Leave a Reply