What if Robert Waldinger discussed happiness with modern psychology experts?

Introduction by Robert Waldinger

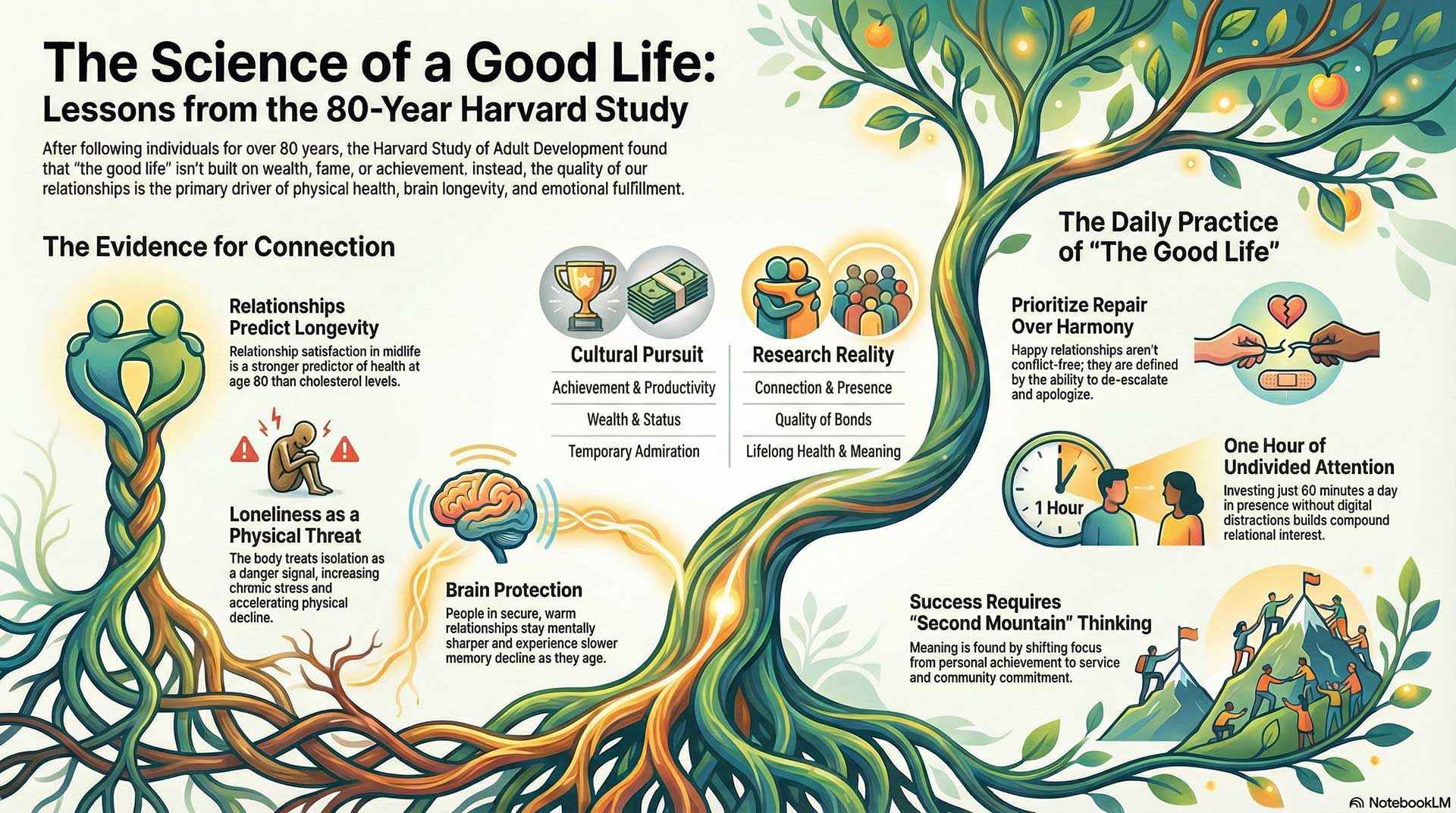

When people hear that an 80-year study has discovered the secret to a good life, they often expect something complex. A rare personality trait. A special mindset. Maybe discipline, achievement, or intelligence.

But the most surprising finding from decades of research is also the simplest:

the quality of our relationships predicts the quality of our lives.

Across generations, careers, personalities, and backgrounds, the same pattern appeared again and again. People who stayed connected lived longer. They stayed mentally sharper. They recovered better from hardship. And perhaps most importantly, they felt their lives mattered.

We tend to organize our priorities around productivity because productivity is measurable. Relationships are not. So they get postponed. We invest in work first, and connection later, assuming we will return to it when life slows down.

But life does not slow down on its own.

It changes only where attention changes.

This conversation explores a different way to measure success. Not by what we accumulate, but by what we sustain. Because a good life is not built in dramatic moments. It is built in repeated acts of presence over time.

(Note: This is an imaginary conversation, a creative exploration of an idea, and not a real speech or event.)

Topic 1: The Real Predictor of Happiness

Robert Waldinger:

When people hear the conclusion of our study, they often nod politely, like it’s a nice sentimental idea. Then they go right back to chasing the same trophies that keep them busy and isolated. So I want to begin with the question that forces us to get honest.

Why do relationships predict happiness and health more than money or status?

Viktor Frankl:

Because money and status cannot answer the deepest question a human being lives with. Do I matter to someone? Am I seen? Meaning is not a private luxury. It is often experienced through love, responsibility, and belonging. When a person is connected, suffering becomes bearable. When a person is alone, even comfort becomes hollow.

Brené Brown:

Because relationships regulate the nervous system. When people feel emotionally safe, they can face shame, failure, and uncertainty without collapsing. Money can buy convenience, but it cannot buy belonging. And belonging is the foundation for courage. Without it, people become guarded. Guarded people cannot experience joy fully.

Martin Seligman:

From a wellbeing perspective, relationships are a major pillar. Positive emotion, engagement, meaning, accomplishment, those matter. But relationships amplify all of them. They make victories sweeter, losses less devastating, and daily life more resilient. Social connection is not just a pleasant addition. It is a core ingredient.

Esther Perel:

Relationships also give identity. We become ourselves in front of others. A career can give status, but intimacy gives truth. And many people choose status because it is controllable. Relationships are not controllable. They require vulnerability. But that vulnerability is where the real nourishment is.

Dan Buettner:

In the Blue Zones, where people live the longest, social connection is not optional. It’s designed into daily life. People belong to groups. They eat together. They help each other. That reduces stress hormones, increases movement, and creates purpose. Wealth is not the common factor. Community is.

Robert Waldinger:

So connection is not a soft idea. It’s biological. It’s psychological. It’s meaning. And it’s designed into human survival.

Now let’s push into the cultural trap.

What do people misunderstand about “success” that keeps them lonely?

Brené Brown:

They confuse admiration with love. They think if they become impressive enough, they’ll feel worthy. But admiration is not intimacy. Admiration can vanish overnight. Love is built through consistency, honesty, and repair. When people chase success to outrun shame, they end up with a life that looks full but feels empty.

Martin Seligman:

They misunderstand that achievement is not the same as wellbeing. Achievement can be part of wellbeing, but it’s only one piece. Many high achievers have high accomplishment scores and low relationship scores, and the relationship deficit shows up later as depression, health decline, or regret.

Viktor Frankl:

They misunderstand what they are truly seeking. Often they believe they are seeking success, but they are seeking significance. And significance comes from being needed and being loved. A person can be celebrated publicly and starved privately. The misunderstanding is believing that applause will satisfy the hunger for meaning.

Dan Buettner:

They misunderstand the environment. Modern life is built to isolate. Big houses, long commutes, individual screens, convenience that removes human contact. People blame themselves for loneliness, but a lot of it is structural. Success in a disconnected environment often means becoming even more disconnected.

Esther Perel:

They misunderstand that intimacy requires time, attention, and presence. Many people treat relationships like accessories that should fit around their schedule. But relationships are not decorations. They are living systems. If you starve them, they don’t just stay the same. They decay. And then you wake up shocked that your life feels cold.

Robert Waldinger:

Yes. The misunderstanding is thinking success automatically delivers connection, when it often demands sacrifice of the very things that create connection.

Now the most practical question.

If someone has one hour a day, what is the highest-leverage relationship habit?

Martin Seligman:

One hour of undivided attention with another person. No multitasking. No phone. Ask one meaningful question and listen. The effect is compound interest. Relationships strengthen through repeated moments of being fully present.

Esther Perel:

Make it a ritual, not an intention. A walk together. A shared meal. A daily check-in where you ask, “How are you really?” Not as a greeting but as an invitation. Rituals protect love from the chaos of life.

Brené Brown:

Practice the courage of going first. Send the text. Make the call. Apologize quickly. Say what you appreciate. One hour a day of reaching out, repairing, and expressing gratitude changes relationships because it changes the emotional climate.

Dan Buettner:

Design your hour to create community, not just connection. Join something that meets regularly. A group walk, volunteering, faith community, hobby group. The reason is simple. When connection is built into routine, it doesn’t depend on motivation. It becomes normal.

Viktor Frankl:

Use that hour to give yourself away to someone. Serve. Encourage. Listen without making it about you. The highest leverage habit is to become a person others experience as a refuge. When you give meaning, you receive meaning.

Robert Waldinger:

Let me close with the simplest summary our research supports. The good life is not built in one grand decision. It’s built in repeated small moments of attention.

And the tragedy is not that people don’t know this.

The tragedy is that people postpone it.

In the next topic, we’ll explore loneliness directly. Not as a personal weakness, but as a modern condition that damages the body and the mind, and what it really takes to rebuild connection.

Topic 2: Loneliness, Stress, and the Body

Lisa Feldman Barrett:

People talk about loneliness as if it’s a feeling that comes and goes. But the body treats loneliness like a signal of danger. If the brain predicts you’re on your own, it reallocates resources toward survival. Over time, that reshapes health, mood, and even personality.

So let’s begin with the foundation.

Why does loneliness damage physical health so profoundly?

Robert Waldinger:

In our study, loneliness wasn’t just sadness. It predicted decline. People who were isolated didn’t simply report feeling worse. They had worse outcomes. Loneliness increases stress and decreases support. The body is not designed to thrive without reliable social buffering.

Johann Hari:

Loneliness is a form of disconnection, and disconnection is a social wound. When people lack belonging, they often self-medicate with screens, substances, or compulsive work. Those behaviors have physical consequences. But the deeper issue is that loneliness removes the sense of being anchored in community.

Kelly McGonigal:

Loneliness is stressful because it signals threat without relief. Stress itself is not always harmful. It becomes harmful when it’s chronic and you have no recovery. Social connection is one of the strongest recovery mechanisms. A supportive relationship can literally shorten the stress response.

Gabor Maté:

Loneliness is often a symptom of disconnection from the self as well as from others. When people do not feel safe to be themselves, they adapt by suppressing feelings, needs, and authenticity. That suppression is stress. And chronic stress is the soil where illness grows.

Matthew Lieberman:

The brain treats social pain like physical pain. When we are excluded, similar neural circuits activate. That’s not poetic. That’s wiring. The body reacts as if something is wrong, because historically something was wrong. Isolation meant danger. So loneliness is not merely emotional. It’s biological alarm.

Lisa Feldman Barrett:

Exactly. Loneliness is a prediction of risk. And risk states change the body.

Now the second question.

How does chronic stress reshape personality and relationships over time?

Johann Hari:

Chronic stress narrows your world. You become less curious, more defensive, more reactive. When people are stressed, they stop investing in relationships because relationships require emotional bandwidth. But then the stress gets worse because connection is missing. It’s a trap.

Kelly McGonigal:

Stress can make people more self-protective. They interpret neutral cues as threats. They withdraw or lash out. It becomes harder to repair conflict because the nervous system is already overloaded. Also, stressed people often believe they are a burden, so they isolate, which increases stress again.

Gabor Maté:

Chronic stress changes attachment patterns. People become avoidant, controlling, or dependent. They may seek relief through pleasing others or through shutting down. Over time, the body learns that closeness equals danger, because closeness might require vulnerability. So people either cling or flee.

Matthew Lieberman:

Stress biases perception. It makes you less able to mentalize, meaning less able to accurately read others’ intentions. That causes misunderstandings and conflict escalation. You also become less rewarding to be around, not because you’re bad, but because your brain is conserving resources and prioritizing threat detection.

Robert Waldinger:

In long-term data, you see this reflected as relationship quality declines. And then people blame the relationship. They say, “We grew apart.” But often it’s stress, untreated, unspoken, unbuffered. Without support, stress turns people inward, and that inward turn erodes connection.

Lisa Feldman Barrett:

That’s crucial. People think stress is a private problem. It’s a relational problem too.

Now the third question.

What is the most realistic way to rebuild connection for someone who feels isolated?

Kelly McGonigal:

Start with small, repeatable contact. Not grand reinvention. One reliable weekly commitment. A class, a group walk, volunteering, a club. Connection grows when it becomes routine, not when it depends on bravery every time.

Johann Hari:

And rebuild meaning alongside connection. People often seek connection after they already feel ashamed or broken. It helps to join something where you contribute. Community forms fastest around shared purpose. Doing something with others creates belonging naturally.

Matthew Lieberman:

Also, reduce the threat prediction. If your brain expects rejection, you will interpret everything as rejection. The realistic path is to create low-stakes interactions that prove safety. Over time, the brain updates its model. This is why repeated friendly contact matters more than one intense conversation.

Gabor Maté:

I would add self-compassion. Many isolated people carry the belief, “I am unlovable” or “I’m too much.” That belief shapes everything. Reconnection requires truth-telling, gently, about what you need and why you withdrew. Therapy can help, but so can honest conversations with one safe person.

Robert Waldinger:

And focus on one relationship. People think they need a large social circle. But what matters most is at least one reliable connection. Reach out to the person you trust most and invest there. The good life is not built by collecting acquaintances. It’s built by nurturing bonds.

Lisa Feldman Barrett:

Let me close this topic with a practical takeaway. Loneliness is not a moral failure. It’s a signal. And the body treats it as serious.

If we want health and happiness, we have to treat connection as preventive medicine, not as a luxury we get to after everything else is done.

Next, we’ll talk about conflict and repair. Because relationships are not happy because they never break. They are happy because they know how to repair when they do.

Topic 3: Conflict, Repair, and Emotional Safety

Esther Perel:

People often think the happiest relationships are the ones without conflict. That is a fantasy. All long relationships include disappointment, misunderstanding, and friction. The question is not whether conflict appears. The question is whether the relationship knows how to repair.

So let’s begin with the key tension.

What matters more for lifelong happiness: avoiding conflict or repairing well?

John Gottman:

Repairing well. Conflict is not the enemy. Contempt is the enemy. The happiest couples still argue, but they have what I call repair attempts, small moves that de-escalate. A joke, a softening, an apology, a request for a break. Successful repair keeps physiology from staying in threat mode.

Brené Brown:

Repairing well, because avoidance is often fear dressed as peace. When people avoid conflict, resentment grows underground. Repair requires courage. You have to face discomfort, admit hurt, and stay present. That builds trust. Avoidance breaks trust quietly.

Marshall Rosenberg:

Repair is the path back to needs. Conflict is often the tragic expression of unmet needs. When people learn to translate blame into needs, they reconnect. Avoiding conflict avoids needs. Repair honors needs.

Harriet Lerner:

Repairing well. Avoidance creates a false calm that costs the relationship. Many people would rather be comfortable than be honest. But comfort without honesty is fragile. Repair is honesty with care. It makes the relationship stronger because it proves you can survive truth together.

Robert Waldinger:

Our research supports this. The people who thrived were not the ones who never struggled. They were the ones who stayed engaged. They made the relationship a place where problems could be addressed rather than buried.

Esther Perel:

Yes. Avoidance feels peaceful, but it often produces emotional distance. Repair produces closeness.

Now the second question.

What destroys emotional safety in families and partnerships, even when love exists?

Brené Brown:

Shame and silence. When people cannot talk about hard things, they start performing. Emotional safety dies when someone feels their feelings are too much, or their needs are inconvenient. Love might exist, but the relationship becomes a stage instead of a home.

John Gottman:

The Four Horsemen. Criticism, defensiveness, contempt, stonewalling. Contempt is the most lethal. Eye-rolling, sarcasm, moral superiority. It signals disgust. Once contempt becomes a habit, emotional safety collapses because the relationship becomes a hierarchy.

Marshall Rosenberg:

Judgmental language destroys safety. When people hear blame, they protect themselves instead of listening. Even when love exists, the moment speech becomes violent, meaning it punishes or labels, safety disappears. The antidote is speaking from feelings and needs, not from diagnosis.

Harriet Lerner:

Unspoken power dynamics. One person becomes the decider, the critic, the one who defines reality. The other becomes the appeaser or the withdrawer. Love cannot flourish where people feel they must earn permission to exist. Safety requires mutual respect and room for both voices.

Robert Waldinger:

Also chronic stress. Families under pressure have less bandwidth for empathy. Small irritations become huge. Without support, people turn on each other. Love exists, but the nervous system is overactivated. Emotional safety requires recovery, rest, and relational tending.

Esther Perel:

So safety is not only emotional. It’s also physiological. If the home is a threat environment, people stop sharing truth.

Now the third question.

What does a real repair attempt sound like when pride is high?

Marshall Rosenberg:

It sounds like vulnerability. “When that happened, I felt hurt. I need respect. Can we start again?” Pride wants to be right. Repair wants to be connected. When you speak needs, you invite connection rather than surrender.

Harriet Lerner:

It sounds like taking responsibility without the word but. “I was wrong. I see how I hurt you.” No defense. No explanation. Just ownership. Pride hates that because it feels like loss. But it’s actually strength. It rebuilds safety quickly.

Brené Brown:

It sounds like courage. “I don’t want to fight. I want to understand what I did and what you need.” Pride protects shame. Repair is the willingness to risk being seen as flawed. That’s the doorway back to trust.

John Gottman:

It sounds like softness. “I’m feeling overwhelmed. Can we take a break and come back?” Repair attempts fail when they’re wrapped in sarcasm or contempt. The body needs to calm first. Then the mind can reconnect.

Robert Waldinger:

And it sounds like continuity. “I’m still here. I still care. I want us.” Repair is not one sentence. It is a pattern. Pride falls when a person proves through action that the relationship matters more than winning.

Esther Perel:

Let me close this topic with something people often forget. Emotional safety is not the absence of conflict. It’s the presence of repair.

If you can repair, you can be honest.

If you can be honest, you can be close.

And closeness, over decades, is one of the strongest predictors of a good life.

Next, we’ll talk about aging well and protecting the brain. Because relationships do not only make life happier. They keep the mind alive.

Topic 4: Aging Well and Protecting the Brain

Daniel Kahneman:

Aging is not only a biological process. It is also a story we tell ourselves about time, identity, and what still matters. Many people assume the good life is about maximizing experiences while young, then enduring decline. But the data here suggests something else. The quality of relationships shapes not only happiness but cognition, resilience, and how we remember our lives.

So let’s start with the core question.

Why do warm relationships protect memory and cognition later in life?

Robert Waldinger:

In our study, relationship satisfaction in midlife predicted cognitive health decades later. Warm relationships reduce chronic stress and provide daily cognitive engagement. When people feel supported, they handle adversity with less physiological wear. That matters for the brain.

Laura Carstensen:

As people age, they become more selective. They prioritize emotionally meaningful relationships. Those relationships provide emotional regulation and purpose, both of which protect mental health. Also, social interaction is cognitive exercise. It requires attention, memory, empathy, and language. That keeps neural networks active.

Andrew Huberman:

Stress hormones like cortisol affect the brain, especially regions involved in memory. Warm relationships act as a buffer that reduces chronic stress response. They also influence sleep quality, motivation to exercise, and overall physiological stability. Those factors compound across decades.

Atul Gawande:

Connection protects agency. When older adults remain relationally embedded, they are more likely to stay active, keep routines, and maintain dignity. Isolation accelerates decline because it removes accountability, care, and the practical support that keeps people functioning.

Mary Pipher:

Warm relationships protect identity. Older adults who feel valued and needed stay psychologically alive. The mind deteriorates faster when life feels like waiting. Relationships give people a reason to stay engaged, to tell stories, to laugh, to mentor, to participate.

Daniel Kahneman:

So the brain is not only a machine. It is a social organ. And stress, meaning, and engagement shape how that organ ages.

Now the second question.

What habits keep older adults emotionally alive instead of shrinking inward?

Laura Carstensen:

Maintain close ties intentionally. Regular calls, visits, shared meals, small rituals. And choose relationships that are emotionally nourishing. Aging is too short for chronic toxicity. Emotional aliveness comes from meaningful connection.

Atul Gawande:

Preserve autonomy and purpose. That means designing environments where older adults can still contribute and make decisions. The habit is not just socializing. It’s continuing to matter. Purpose is medicine.

Andrew Huberman:

Sleep, movement, light exposure, and stress regulation. These are habits that support emotional stability. When the body is regulated, people have more capacity for social interaction. Also, learning new skills is powerful. It keeps the brain plastic and keeps identity expanding.

Mary Pipher:

Intergenerational contact. It prevents the older person from becoming trapped in the past. Teaching, storytelling, helping with grandchildren, mentoring, volunteering. Those habits make older adults participants, not spectators.

Robert Waldinger:

And investing in friendships, not just family. Friendships are often chosen bonds. They can be emotionally rich and reduce loneliness. Many people neglect friendships midlife and regret it later. Emotional aliveness is often built through peers.

Daniel Kahneman:

So aliveness is not about denying aging. It’s about staying connected, purposeful, and engaged.

Now the third question.

How should we think about regret and meaning as time feels shorter?

Mary Pipher:

Regret is often grief for unlived connection. People regret time lost to pride, busyness, or silence. Meaning comes from repair and presence. The habit is making amends sooner, not later. Time shortens. Love should not wait.

Robert Waldinger:

We found that late-life wellbeing is shaped by whether people believe their lives were relationally meaningful. Regret can become a teacher. It can guide you back to people. The question is not, “Did I achieve enough?” It’s, “Did I love well, and did I let myself be loved?”

Atul Gawande:

Meaning is tied to dignity and choice. As time shortens, the important shift is from extending life at any cost to living according to values. Regret often comes from living someone else’s script. Meaning comes from aligning daily life with what you truly care about.

Andrew Huberman:

From a neurobiological angle, regret is a prediction error. The brain compares what happened to what could have happened. It can be painful, but it can also motivate new behavior. The key is to use regret as information, not as identity. Repair relationships, create new routines, and move forward.

Laura Carstensen:

Time perspective changes priorities. When time feels limited, people naturally seek emotional meaning. Regret often diminishes when people invest in what matters now. Meaning is created through attention. What you repeatedly attend to becomes your life.

Daniel Kahneman:

Let me close this topic with an observation. The remembering self judges life largely by patterns and peaks, not by spreadsheets of achievement. Warmth, connection, dignity, and repair create the memories that make a life feel worth living.

Next, we move to the daily practice of the good life. Because the good life is not a theory. It’s a set of small behaviors repeated for decades.

Topic 5: The Good Life as a Daily Practice

Viktor Frankl:

People often ask for the secret to a good life as if it were a hidden technique. But the good life is not found. It is built. It is built in ordinary days, through the choices that form your character and your relationships.

Let us begin with what is practical, not romantic.

If the good life is built daily, what is the smallest repeatable practice that matters most?

Robert Waldinger:

A daily moment of genuine connection. One conversation where you are fully present, no phone, no rushing. Ask a real question and listen. That small moment, repeated for years, changes the trajectory of a life.

Thich Nhat Hanh:

To breathe and to listen. When you breathe mindfully, you return to yourself. When you listen deeply, you return to the other. The smallest practice is one breath before you speak, and one breath while you listen. It creates peace inside the body, and that peace spreads.

James Clear:

Make connection easy and automatic. The smallest practice is a tiny habit that lowers friction. A daily message to a friend. A scheduled walk with your partner. A family dinner two nights a week. Small actions, repeated, become identity. You become the kind of person who shows up.

Arthur Brooks:

I would say daily acts of love and service. Happiness is not a feeling you chase. It is a byproduct of giving and receiving love. The smallest practice is to ask, “How can I make someone else’s day better?” Then do it, even in a small way.

David Brooks:

Daily presence. Most people live in a blur of performance. A good life is built by showing up to the people in front of you. Look into someone’s eyes and treat them like a soul, not a task. That is small. And it is rare. And it changes everything.

Viktor Frankl:

Yes. The smallest practice is to choose love in one ordinary moment. Meaning is not built by intensity. It is built by fidelity to what matters.

Now the second question.

How do we choose relationships that nourish us rather than drain us?

Thich Nhat Hanh:

Choose relationships where you can be peaceful. If someone brings you constant agitation, you must look carefully. Love is not only passion. Love is also the capacity to help each other suffer less. Nourishing relationships make your body calmer, not tighter.

Robert Waldinger:

Look for reliability and kindness. People often choose relationships based on charm or excitement, but the long-term predictors are simpler. Do you feel safe. Do you feel respected. Can you repair. Those qualities nourish. Without them, even love becomes exhausting.

James Clear:

Pay attention to patterns, not promises. A nourishing relationship is one where effort is reciprocated over time. A draining relationship is one where you keep making exceptions for behavior that repeats. The habit is to believe patterns. Then set boundaries accordingly.

Arthur Brooks:

Also choose people who help you grow in virtue. There is a kind of companionship that pulls you downward through cynicism, gossip, or resentment. Nourishing relationships encourage your better self. They do not flatter you. They elevate you.

David Brooks:

Ask one simple question. After I spend time with this person, do I feel larger or smaller. Nourishing relationships enlarge your spirit. Draining relationships shrink it. And if you keep choosing shrinking, you will wake up with a small life.

Viktor Frankl:

And remember, boundaries are not the opposite of love. They are often the protection of love.

Now the third question.

What does it mean to live a good life when life includes suffering?

Arthur Brooks:

It means accepting that happiness is not constant pleasure. A good life includes pain. The goal is not to avoid suffering. The goal is to meet suffering with love and purpose. People who live well learn to transmute pain into compassion rather than bitterness.

Viktor Frankl:

Suffering is not good in itself. But when suffering is unavoidable, we are still free to choose our attitude. The good life is not a life without tragedy. It is a life where tragedy does not destroy meaning. Meaning is found in how we respond, in love, in service, in responsibility.

Thich Nhat Hanh:

Suffering can be a teacher if we do not run from it. When we hold suffering with mindfulness, it transforms. We see that suffering is shared. That creates compassion. And compassion is a deep kind of happiness, quieter than excitement but stronger than despair.

Robert Waldinger:

Our study showed that people with strong relationships did not escape suffering. They endured it better. They had someone to call. Someone who sat with them. Someone who helped them remember they were not alone. That is what makes suffering survivable.

David Brooks:

A good life includes what I would call the second mountain. The first mountain is achievement. The second is commitment, love, community, and moral purpose. Suffering often knocks people off the first mountain and forces them to ask what they truly live for. If they answer well, they become deeper.

Viktor Frankl:

Let me close with this. The good life is not a trophy. It is a practice of attention.

Attention to the people you love.

Attention to your responsibility.

Attention to the meaning available in the moment you are living.

And when you practice that attention daily, you do not only become happier. You become more human.

Final Thoughts by Robert Waldinger

After following people for most of their lives, one lesson stands above the rest. The good life is not something you find at the end of a path. It is something you practice along the way.

Relationships do not need to be perfect. They need to be tended. Repair matters more than harmony. Presence matters more than intensity. And consistency matters more than grand gestures.

Many people wait for the right time to reconnect, to apologize, to listen, or to show appreciation. The study suggests the right time is usually sooner than we think. The small conversations we postpone quietly shape the years we later remember.

Happiness is often imagined as a personal achievement. In reality, it is a shared construction. It emerges where attention, care, and time meet another human being.

If there is one practical conclusion, it is this:

invest in people while life is ordinary.

Because when decades pass, what remains meaningful is rarely what filled our schedules. It is who filled our days.

Short Bios:

Robert Waldinger — Psychiatrist and director of the Harvard Study of Adult Development, researching how relationships influence lifelong health and happiness.

Martin Seligman — Psychologist and founder of positive psychology, known for research on wellbeing, meaning, and human flourishing.

Brené Brown — Research professor and author studying vulnerability, courage, shame, and connection in human relationships.

Esther Perel — Psychotherapist specializing in relationships, intimacy, and modern emotional connection.

Viktor Frankl — Psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor who developed logotherapy, focusing on meaning as the central human motivation.

Dan Buettner — Longevity researcher and explorer of Blue Zones, studying communities where people live longer, happier lives.

Lisa Feldman Barrett — Neuroscientist researching how emotions are constructed by the brain and how social context shapes wellbeing.

Johann Hari — Writer and researcher examining loneliness, addiction, and the psychological effects of disconnection.

Kelly McGonigal — Health psychologist studying stress, resilience, and how social connection changes physiological responses.

Gabor Maté — Physician and author exploring trauma, addiction, and the mind-body relationship in health.

Matthew Lieberman — Social neuroscientist studying the brain’s need for social connection and its impact on behavior.

John Gottman — Psychologist known for decades of research on relationship stability, communication, and conflict repair.

Marshall Rosenberg — Psychologist and founder of Nonviolent Communication, emphasizing empathy and needs-based dialogue.

Harriet Lerner — Psychologist and author focusing on emotional patterns, boundaries, and family dynamics.

Daniel Kahneman — Psychologist and Nobel laureate researching decision-making, memory, and experienced wellbeing.

Laura Carstensen — Psychologist studying aging, emotional regulation, and how time perspective changes priorities.

Andrew Huberman — Neuroscientist researching behavior, stress regulation, and brain plasticity.

Atul Gawande — Surgeon and writer exploring healthcare systems, aging, and quality of life.

Mary Pipher — Psychologist focusing on life transitions, aging, and emotional resilience.

Thich Nhat Hanh — Zen teacher teaching mindfulness, compassion, and attentive living.

James Clear — Writer on habits and behavior change, emphasizing small consistent actions over time.

Arthur Brooks — Social scientist studying happiness, purpose, and moral development.

David Brooks — Writer examining character, community, and meaning in modern life.

Leave a Reply