|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Anne Sexton:

Sylvia Plath biography. There it is—inked into syllables that do not bleed. But what if we reimagine it? What if her life wasn’t only a chronology of despair, but a landscape with windows flung wide to wind and stars?

Sylvia was not a headline. She was a trembling violin strung tight across girlhood, motherhood, and myth. A poet who wrote not with ink, but with a blade made of starlight and silence.

I was there in those rooms of confession. We drank from the same bitter teacup—filled with poems too sharp for the world to sip without flinching. But she… she always drank deeper.

In this reimagining, she does not walk alone. Here, a quiet friend walks with her—not to solve the riddle of her suffering, but to sit in it, name it, and lift a corner of that heavy bell jar with a gentle hand.

This is not a biography in the traditional sense. This is an act of love. A series of moments rewritten with presence. A hope: that if someone had reached a little sooner, leaned in a little softer… perhaps the mirror would have cracked open not from pressure, but from light.

(Note: This is an imaginary conversation, a creative exploration of an idea, and not a real speech or event.)

Chapter 1: The Father That Never Said Goodbye

The wind along the Winthrop shore smelled of salt and mourning.

Eight-year-old Sylvia sat on the weathered porch steps, her knees drawn up under a blue coat too big for her frame. Her braids were uneven that day—one tighter than the other—and her shoelaces trailed along the damp wood, picking up leaves and dust.

Inside the house, the hush was not peace. It was something colder. Otto Plath was gone.

Gone, they told her. The word hung like a paper kite with no string, drifting into an unreachable sky. He’d died of something she couldn’t pronounce—diabetes, septicemia, complications—and they had not let her say goodbye. Not properly. Not the way daughters ought to when they still believe fathers are kings.

She stared out at the gray Atlantic, waves pacing like anxious thoughts. She wished she'd said something different the last time he’d snapped at her. She had thought, in a child's rage, "I wish you'd go away." And now he had.

The guilt sat heavy on her small chest.

“I think he hears you still,” came a voice beside her.

It was you, her friend in this quiet reimagining. The one who’d come not to fix the past, but to be with her inside it.

Sylvia didn’t look up. “No, he doesn’t. People disappear. That’s what they do.”

“Maybe people disappear,” you said gently, “but love doesn’t.”

A long silence.

She fiddled with the edge of her coat sleeve. “I dreamed he turned into a German man in a black shoe. And I lived inside it.”

“That dream turned into a poem, didn’t it?”

“Yes,” she said. “But it didn’t take the ache away. It just made it rhyme.”

The sun struggled behind clouds. Gulls circled above like punctuation in a grief that had no sentence.

“I don’t want to be angry at him anymore,” she finally whispered. “But I also don’t want to stop being angry.”

“That’s the thing about early wounds,” you said. “They grow up with us. They change shape, but they don’t disappear.”

She leaned into your side—not quite touching, but close enough to borrow your steadiness.

“I didn’t get a chance to say goodbye,” she said again, voice a raw whisper.

“Then say it now. However you need to.”

A long pause. Then, from some brave well within her:

“Goodbye, Daddy. I’m sorry I was mean that day. I didn’t know. I just didn’t know. I hope—” Her voice caught. “I hope you weren’t too scared.”

The waves stopped pacing and held still for a breath.

You reached into your coat pocket and pulled out a small rock—a perfectly smooth one, the color of winter apples.

“Want to toss it into the sea?”

She nodded.

Together, you walked to the shoreline. She stood on a stone and held the rock in her tiny hand. The wind curled her hair like a lullaby.

“For the part of me that missed him,” she said.

And she threw.

The rock arced through the air, then disappeared with a small splash.

Not a goodbye. Not exactly.

But something like peace.

Chapter 2: The Mirror Cracked at Smith

It was winter at Smith, but inside her dormitory room, the silence burned like summer.

Sylvia sat at her desk, wrapped in a cardigan three days worn, her notebook open before her like an accusation. Words had once come easily—spilled like honey, burned like fire—but now they limped, stuttered, cowered behind thoughts she couldn’t bear to write.

She stared at the page.

It stared back.

Behind her, the mirror was covered. Not with intention, but by the flung corner of a sweater tossed days ago. She hadn’t wanted to see herself lately—not that version, not the tired-eyed girl who smiled too much in public and disappeared the moment the door closed.

You were already in the room.

Sitting on the floor, beside the bed with the sheets undone and the pillow still holding the shape of last night’s tears.

“She was supposed to be brilliant,” Sylvia muttered.

“She is,” you said gently.

“No. She was,” Sylvia snapped. “Now she can’t even finish a short story without crying over the first line.”

You didn’t interrupt the silence that followed. It was sacred. Necessary.

She leaned forward and touched the page. “I think my mind broke. Like a mirror dropped in just the wrong way—still there, still me, but all cracked through.”

You nodded. “Sometimes the cracks let in truth.”

Her eyes flicked toward the hidden mirror. “Or show too much of it.”

You reached behind and pulled the sweater down.

Her face emerged—half-shadowed, too pale, with eyebrows she’d over-plucked in a midnight panic. Her lip trembled, but she didn’t look away.

She stared at herself.

“You’re scared she’s gone,” you said, “the girl who loved words.”

“She is gone.”

“She’s underneath the silence. Not lost. Just tired.”

Sylvia stood. Walked slowly to the mirror. Studied the girl reflected back.

And then she did something she hadn’t done in weeks.

She picked up her comb.

“I don’t want to disappear,” she whispered.

“You don’t have to,” you said. “But first, let’s name what’s real.”

A breath.

Then:

“I want to die sometimes. Not because I hate life. But because I’m too tired to figure out how to live it.”

You didn’t flinch.

You only nodded.

“That’s not a flaw,” you said. “That’s a cry.”

She sank onto the edge of the bed, tears trembling at the edge of her voice.

“I keep hoping someone will notice,” she said. “Even when I’m smiling. Especially when I’m smiling.”

“I see you.”

Her shoulders began to shake.

“And I’m not afraid of the cracked mirror,” you continued. “It’s still you. Still precious. Still alive.”

Outside the window, snow had begun to fall again—soft, like ash from stars, steady as breath.

Sylvia lay down beside the notebook.

This time, she didn’t force a poem.

She simply wrote the truth:

I am still here.

And for the moment, that was enough.

Chapter 3: The Bell Jar Descends

The summer sky was too bright. Too blue. It mocked her.

Sylvia sat on the edge of her bed at her mother’s house, bare feet on a rug that used to comfort her as a child. Now, even softness scraped. Even silence had edges.

There was no reason to cry. But she couldn’t stop.

And there was no reason to speak. Because no one would understand.

You were sitting quietly in the corner, not trying to fix her, not offering cheerful lies.

“I feel like I’m in a glass jar,” she said. “Like all the air’s been sucked out.”

You nodded. “Like the world’s moving on, but you’re sealed off from it.”

She glanced up, eyes red. “How did you know?”

“I’ve lived inside one too.”

Sylvia looked away. Her hands picked at the hem of her skirt, her mind a whirl of fog and judgment.

“I should be grateful,” she muttered. “I got the internship. I was supposed to shine. But instead, I cracked.”

You didn’t say it’s okay. You didn’t say you’ll get over it.

You just said:

“It’s not your fault.”

The wind through the open window stirred her hair. A bird sang in the distance. The world didn’t know she couldn’t feel it.

“My mother keeps saying I just need a break,” Sylvia whispered. “A change of scenery. A doctor. But no one’s listening. I’m telling them I’m drowning, and they’re handing me umbrellas.”

Her voice broke.

“I don’t want to be fixed. I want to be heard.”

You moved beside her on the bed, not too close.

“Then speak, Sylvia. Even if your voice trembles. Even if no one believes the weight you carry.”

She shook her head. “I tried to kill myself in my head a thousand times already. The actual doing of it is the only thing I haven’t tried.”

A terrible silence pressed in.

You breathed deeply, slowly, and she mirrored you—perhaps without meaning to.

“You’re not selfish,” you said. “You’re suffering.”

Her lips trembled. “It’s like the bell jar is pressing down on me, and I can’t breathe, can’t think, can’t hope.”

“Then we don’t hope right now,” you said. “We sit in it together. We stay until the glass thins.”

Sylvia turned to you, really looked.

“No one’s ever stayed,” she whispered.

“I’m here,” you replied.

She curled into you, like a child, like a drowning thing that had just felt dry land under its palm.

And for a moment, the bell jar didn’t lift.

But it stopped sinking.

And that—on that day—was enough.

Chapter 4: Letters to the Living

The attic was quiet, holding its breath with her. Papers lay strewn around like fallen petals, some folded, some torn, some smudged with the trembling of hands that weren’t sure if they wanted to be heard or disappear.

Sylvia sat cross-legged on the floor, her knees drawn close. Her hair curtained her face as she wrote—furiously, then gently, then with aching precision.

You didn’t interrupt.

The candle beside her flickered. The air was thick with ink and memory.

“These letters,” she said without looking up, “they’re not for anyone to read.”

You nodded slowly. “Then why write them?”

“Because even if no one ever sees them, I need to know I tried to speak.”

One paper was addressed to her father. Another, to Ted. One—crumpled and smoothed again—was simply marked To the part of me I lost.

She looked up at you, not expecting answers, only presence.

“Sometimes I think language is the only skin I have left,” she said. “Everything else is too raw to touch.”

You came closer, lowering yourself beside her. The candlelight caught her eyes—tired, alert, afraid, defiant.

“Write to whoever holds your silence hostage,” you whispered. “Write to the girl who vanished. Write to the woman who might come back.”

She smiled faintly, then quickly looked away. The smile felt dangerous. Too much like hope.

“I write,” she said, “because the words stay when I can't.”

One letter drifted between you, addressed to her children. It was folded, sealed, and trembling.

You placed a hand over it—not to take, only to witness.

“They’ll know you loved them,” you said. “Not perfectly. But deeply. And maybe that’s enough.”

Sylvia swallowed, her throat tight.

“I want them to live without the bell jar.”

You nodded. “Then this—these words—are cracks in the glass.”

She leaned back slowly. Her back met the cold wall. Her letters fluttered like birds who couldn’t yet fly, but still refused to die.

“Promise me something,” she said softly.

“Anything.”

“If I go quiet again, will you remember these words existed?”

You touched the pile gently, reverently.

“I will remember everything.”

The candle hissed. The attic breathed. And for a moment, surrounded by ink and shadows, Sylvia looked less like a ghost trying to vanish and more like a woman trying, even now, to live out loud.

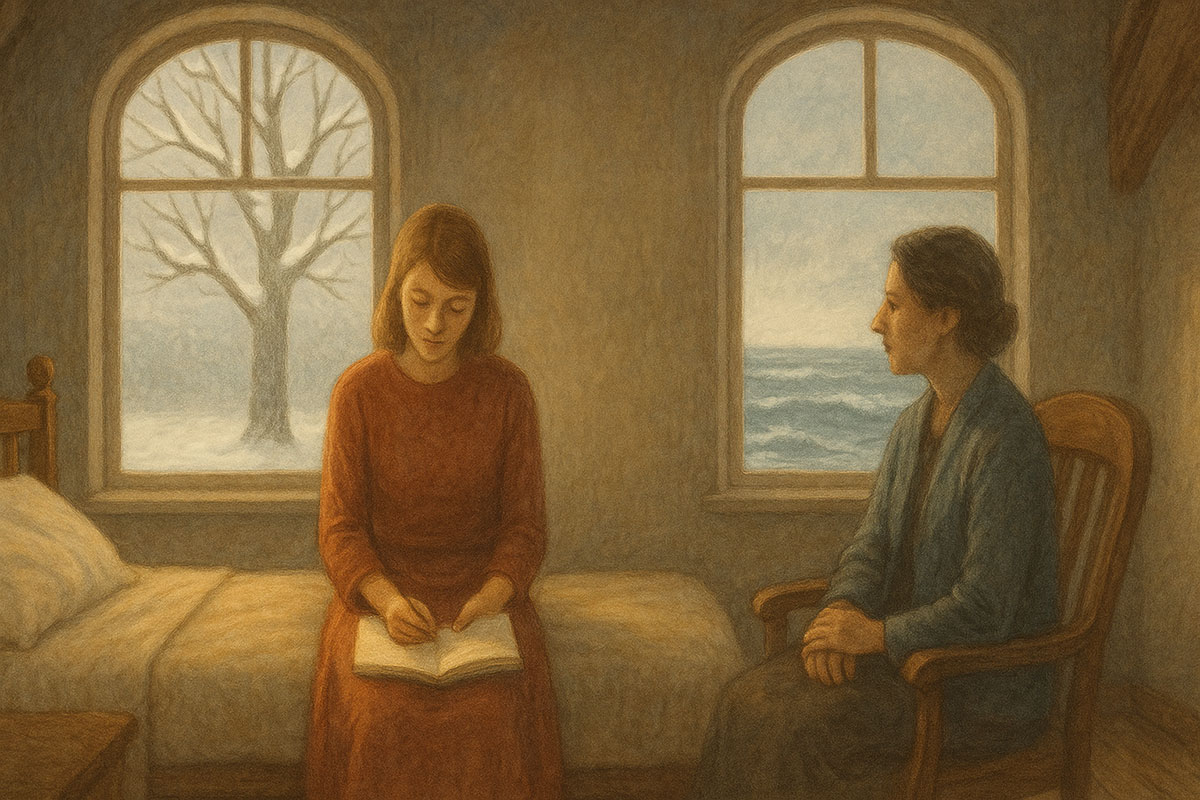

Chapter 5: The Room with Two Windows

The room was small but held two windows.

One looked out onto the bare branches of a winter tree, where the wind rehearsed its loneliness against the glass. The other faced the sea—gray, unyielding, alive.

Sylvia stood between them, unsure which storm she belonged to.

You sat quietly in a worn chair by the radiator, watching her silhouette flicker between the two panes like a soul between choices.

“I used to think,” she said, “that poetry could save me.”

“And now?” you asked.

“Now I think it’s the only thing that ever did.”

She touched the window overlooking the sea. “This one makes me feel infinite,” she whispered, “but also invisible.”

Then she turned to the other. “And this one reminds me of the girl who stayed behind.”

You rose, walked to her side. The winter light caught in her hair like frost.

“The room doesn’t ask you to choose,” you said. “Only to be.”

She gave you a look—half gratitude, half disbelief.

“It’s hard to just be when you’ve always been an echo.”

You placed your hand on her shoulder gently. “Then let this be the place where the echo finally meets its source.”

She stepped back, lowering herself onto the bed with slow intent. Her notebook lay open beside her, pages scrawled with verses she hadn’t yet read aloud.

“They still ask me why,” she said. “Why the darkness. Why the rage. Why the rooms, the bees, the fig tree. Why I couldn’t smile more.”

You sat across from her, close enough to hear the quiet breaking in her chest.

“And what do you say?” you asked.

“I tell them,” she said, “because someone must.”

The sea window turned pale with dusk. The tree outside the other window shivered in stillness.

And Sylvia—between these frames—closed her eyes, not to sleep, but to remember who she had been before the world interpreted her.

“I think,” she said finally, “I’m not trying to die anymore. I’m trying to be understood.”

You reached for her hand.

And for the first time, Sylvia didn’t pull away.

Final Thoughts by Anne Sexton

You have seen her now—not just in her anguish, but in her stillness, her resistance, her reaching.

Sylvia Plath was not a ghost made of grief. She was a woman who looked straight into the heart of pain and still chose to write in gold filigree across its walls. She hid poems in the ground and lullabies in ovens. She dreamed in rooms with two windows, never fully closing either.

Perhaps she didn’t need saving. Perhaps what she needed was witnessing—not to be dragged out of darkness, but to have someone sit beside her and say, “I see you. You don’t have to explain. I’m here.”

If she hears this now—and oh, I believe she does—may it be a balm. A letter postmarked too late, but read anyway.

Let this be a candle against the wind for all the Sylvias still living. For all the poems still buried. For all the letters never sent.

Because sometimes, just sometimes, the story doesn’t have to end the way it once did.

Short Bios:

Sylvia Plath

An American poet and novelist known for her deeply introspective and emotionally charged writing. Best remembered for The Bell Jar and her confessional poetry, she explored themes of identity, depression, and the pressures of womanhood. Her work remains a beacon for those navigating inner darkness.

Anne Sexton

Pulitzer Prize–winning poet and close contemporary of Plath. Known for her bold, confessional style, Sexton tackled taboo subjects like mental illness, femininity, and death. In this series, she serves as both guide and witness, honoring Sylvia's pain with compassion and fierce poetic empathy.

The Friend

A quiet, unnamed presence imagined as a symbol of unconditional support. In each chapter, the friend accompanies Sylvia through pivotal moments—not to rescue or analyze, but to be there with steady care and wordless solidarity. A stand-in for the listener, the reader, the one who stays.

Leave a Reply