|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Saul Bellow:

It begins with a contradiction—how the child of Jewish immigrants, born in Lachine, Quebec and raised in the slums of Chicago, would one day sit in Stockholm as a Nobel Laureate, and yet still feel estranged from both the honor and the crowd. I’ve often written that the soul seeks more than the social order allows. That’s true of me too. This series is not a grand survey of achievements. It is, rather, a return to the secret places—tenements, divorces, park benches, silences—where my voice was first sharpened, then softened. With a friend beside me, and no need to explain too much, I revisit the moments I couldn’t outwrite, only outlive.

(Note: This is an imaginary conversation, a creative exploration of an idea, and not a real speech or event.)

Chapter 1: The Loneliness After Herzog

Setting:

A gray autumn afternoon in Vermont. Saul Bellow sits alone in a worn leather chair by a frost-flecked window. The success of Herzog echoes in headlines folded on the floor, unread. The radiator hums. Wind bends the bare branches outside. A kettle hisses, but he hasn’t moved.

Narrative:

The room smelled of old books, burnt coffee, and loneliness.

Bellow sat still, fingers pressed lightly to his temple, as if searching for the pulse of a thought that refused to land. On the small table beside him, Herzog lay half-open, its spine bent backward like a confession. He hadn’t touched it in days. Maybe weeks. Fame had knocked; it had entered the room uninvited. And yet, Saul felt like a ghost sitting in the center of it.

His friend entered quietly.

“I brought soup,” the friend said, setting the thermos on the sill. “But it’s not going to fix anything, is it?”

Bellow didn’t answer at first. His voice, when it came, was like turning pages in a damp book.

“They love the book, but they don’t know me. That’s the irony. The more I wrote, the less I existed.”

Outside, a single leaf detached and fluttered, suspended in hesitation, before it touched down in the silent yard.

“You always said writing was your way back,” the friend said, easing into the armchair across from him. “But maybe this time, it was a way out.”

Bellow leaned his head back. His eyes searched the ceiling like a man scanning the clouds for rain.

“I put all my grief in Moses Herzog. My divorces. My rage. My maddening little redemptions. And now that they’ve read it, I’m supposed to feel… what? Healed?”

“No,” the friend said gently. “Just less alone.”

There was a long pause.

“But I don’t. I’ve never felt lonelier.”

The friend reached down and picked up the yellowing newspaper with Bellow’s photo beside the word GENIUS. He held it between two fingers, like something fragile.

“They don’t know what it cost,” the friend said. “To write that. To pull your heart out and serve it on a page.”

Saul rubbed his face with both hands. He looked older than yesterday.

“I thought the prize would be peace,” he whispered. “But all I got was silence.”

A log cracked in the fireplace, startling them both.

Then the friend leaned forward, speaking not like someone offering advice, but like someone holding a hand out in the dark.

“What if peace isn’t the prize? What if it’s the permission? To finally be real, without hiding behind language.”

Saul laughed, hollowly.

“You mean stop writing?”

“I mean stop writing like it’s a shield.”

Another long moment passed.

Bellow looked at his own hands—ink-stained, aging, twitching slightly. “I don’t know who I am without the words,” he said. “It’s like I’ve built a house from metaphors and can’t remember how to live in it.”

His friend nodded slowly.

“Then maybe we go outside for a while.”

He stood, went to the door, and opened it.

Cold wind swept in, alive and unforgiving.

“Come on. Just for a walk,” he said.

Bellow stared at the threshold. A walk. So ordinary. So human.

And he stood.

The kettle still hissed on the stove, but neither of them turned it off. They stepped into the wind together.

The headlines stayed behind.

Chapter 2: The Pain of Losing His Brother, Morrie

Setting:

A quiet cemetery in Chicago. Snow begins to fall. Saul Bellow stands by a gravestone, gloved hands in his coat pockets. His breath clouds the winter air. Morrie’s name is etched into the stone, simple, clean. His friend waits a few paces behind, giving space—but not distance.

Narrative:

Snow touched the city like a hush.

It softened the traffic, muted the skyline, and filled the silence between Saul and the gravestone with a strange and aching grace. He had come alone—or so he thought—but as the minutes passed and the cold bit into his knuckles, he heard footsteps crunching behind him.

“I thought you’d be here,” said the friend, quiet as snowfall.

Saul didn’t turn. His gaze was locked on the name: Morrie Bellow. Brother. Fighter. Judge. Storyteller.

“I used to think grief was sharp,” he finally said. “Like a clean wound. But this… this is fog. It seeps in and you don’t notice until you’ve forgotten how to breathe.”

The friend said nothing, only stepped closer.

“We fought,” Saul said, jaw tightening. “We loved each other in the way brothers do—loudly, secretly. Then one day he was just… gone.”

The snow landed gently on the stone.

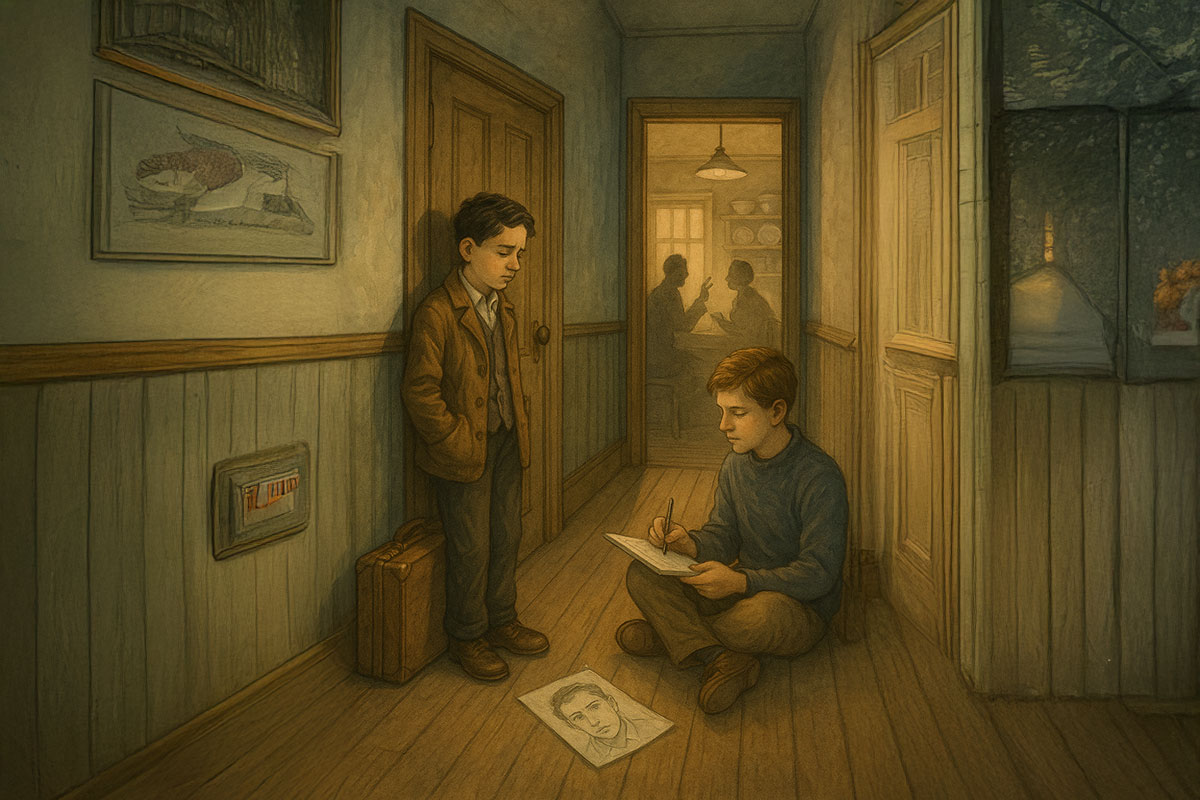

“He was the first person who believed I had a voice,” Bellow went on. “When I was a boy, hiding my stories in the closet, he found them. Read every page. Said, ‘Don’t stop, Saul. The world’s full of noise. Say something worth hearing.’”

“And you did,” the friend offered.

Saul’s breath hitched.

“But I never said thank you.”

He finally looked at his friend. Eyes rimmed red, but dry.

“Everyone tells you to make peace before they die. But no one tells you how to make peace with what you never said.”

The friend knelt, brushed snow off the stone bench beside the grave, and gestured to it. Saul hesitated, then sat beside him. The cold bench welcomed them with indifference.

“I remember,” the friend said slowly, “that night after the funeral, you read me one of your stories. The one about the two brothers. One loud, one quiet. And you said, ‘This is the only way I know how to say goodbye.’”

Saul nodded faintly.

“Do you think he heard it?” he asked.

The friend didn’t answer immediately. He looked at the branches above, collecting snow like forgotten letters.

“I think he knew,” he finally said. “Because love doesn’t wait for perfect endings. It just listens.”

They sat in silence for a while. Wind swept across the graves, carrying the low sound of distant bells. A city still lived around them. But for now, it made room.

Saul reached into his coat and pulled out a folded paper. A letter. Yellowed, creased, familiar.

“I wrote this the day after he died,” he whispered. “But I never read it aloud.”

“Would you like to now?” his friend asked.

Bellow didn’t reply. Instead, he opened it, hands shaking slightly, and held it between them.

Then, with a voice that carried every unsaid apology, he read:

“Morrie,

You were the story before I had stories.

You were the first sentence, the run-on laughter,

the paragraph that interrupted every doubt.

I never told you that I carried you into every page.

You were my measure of truth,

the baritone behind my trembling lines.

Forgive me for the times I wrote you too late.

You deserved better beginnings.I love you.

I miss you.

—Saul”

When he finished, the snow had thickened. The words hung in the air a moment longer, then disappeared like breath.

His friend touched his shoulder. Not to comfort—but to witness.

“Let’s go home,” he said.

But Bellow stayed one more minute.

“I don’t know if I’ll ever stop writing to him,” he said.

“You don’t have to,” the friend replied. “Some letters are meant for the soul.”

They rose together and walked back through the gates, two figures folding into the snowfall, no longer speaking, but no longer silent either.

Chapter 3: The Collapse After the Nobel

Setting:

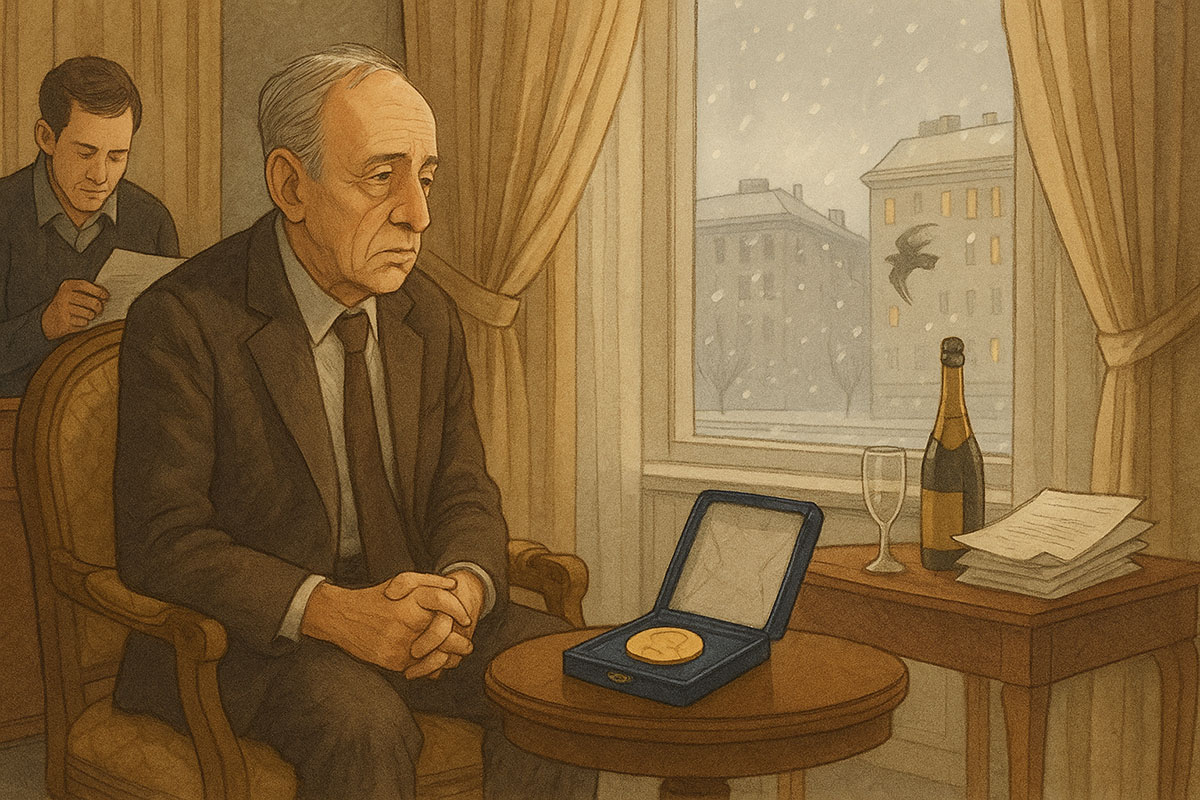

A hotel suite in Stockholm. Night after the Nobel ceremony. Champagne glasses are half-drunk. Saul Bellow stands at the window in formal wear, bowtie loosened, award box unopened on the table. His friend sits on the couch, watching Saul look out at the frost-tinted city.

Narrative:

Fame has a sound.

It is not loud. It is not applause.

It is the silence that follows a standing ovation.

Saul Bellow stood like a statue draped in ceremony. Outside the window, Stockholm shimmered under snow and spotlight. Inside, the warmth had dimmed. The party was over, and the echo of congratulations rang thin in the air.

His friend rose from the sofa, where remnants of celebration—caviar, crumpled napkins, scribbled notes—lay like evidence of something almost joyous.

“You haven’t touched it,” the friend said, gesturing to the small velvet box on the table.

Bellow didn’t turn.

“What happens when the crown lands on the wrong head?” he said softly.

“Is that what you think this is?”

“No,” Saul said, still watching the city. “That’s what the voice in here says.” He tapped his chest. “The one that’s been with me since the first rejection slip.”

He finally turned around. His face—always angular, always sharp—now seemed softened by weariness, not years.

“You know what I thought I’d feel?” he asked. “Relief. Closure. Something clean.”

His friend approached slowly.

“And instead?”

“I feel… gone,” Bellow whispered. “As if I left myself behind in one of the novels, and they gave the prize to the shell that kept going.”

He collapsed into an armchair and covered his face with both hands.

“I should be proud,” he muttered. “Grateful. But all I can think about is how loud it was in that hall… and how alone I felt inside the noise.”

His friend didn’t argue. He walked over to the award box, opened it without ceremony, and placed the gold medallion on the table between them. Its weight glowed in the lamplight—beautiful, still, indifferent.

“This isn’t a finish line,” the friend said. “It’s a mirror.”

Bellow looked up.

“A mirror of what?”

“Of the man who made meaning out of chaos. Who dared to be human when it would’ve been easier to be clever. Of the boy who asked, ‘Do I belong here?’ and answered by building a whole literature of belonging.”

Bellow leaned back, lips parting, but no words came.

“I read Herzog again last week,” the friend said, settling on the ottoman across from him. “You know what line hit me this time?”

Bellow shook his head.

“‘I fall upon myself and tear out the roots. And I wish I knew what to plant instead.’”

The words landed like snow on steel. Quiet. Sharp.

“Maybe this prize isn’t the harvest,” his friend said. “Maybe it’s just another seed.”

Bellow exhaled a breath he hadn’t realized he’d been holding.

“Do you think it’s possible,” he asked, “that I became the man my characters feared becoming?”

“No,” the friend answered without hesitation. “You became the man they hoped could survive.”

They sat in stillness, the gold medallion between them. Not as a crown. Not as a verdict. But as a pause.

Saul finally reached for it.

“It’s heavier than I expected.”

“It always is.”

Bellow looked out the window again. But this time, the lights didn’t mock him—they called him back. Back to story. To sentences. To solitude that was not abandonment, but devotion.

He stood, straighter now.

“I’m not done,” he said. “Not by a long shot.”

His friend smiled, soft and proud.

“I never thought you were.”

They left the medallion on the table and stepped out into the snow, not as laureates or legends, but as two men walking quietly into the next blank page.

Chapter 4: The Silence After Losing His Voice

Setting:

A quiet lake house in Vermont. Early autumn. The wind stirs red and gold leaves outside the screen door. Saul Bellow sits at the kitchen table, a yellow legal pad in front of him. The pen in his hand has not moved for hours. His friend makes tea in the background, not speaking yet.

Narrative:

The page waited.

But he did not come.

He sat before it every day, same time, same ritual—tea steeping, light slanting through the windows, birds drawing question marks in the sky.

But the words had fled.

Not in a storm.

Not in a rebellion.

They had simply… withdrawn. Like a tide that no longer returned.

Saul Bellow stared at the paper as if it had betrayed him.

“It used to come,” he said finally, his voice thin but intact. “Even on bad days. Especially on bad days.”

His friend placed the mug beside him. Chamomile steam coiled between them.

“You think the words have left you,” the friend said.

Saul didn’t answer.

“You think maybe you said it all.”

Still silence.

“I’ve thought that too,” his friend continued gently. “When the work feels finished, but I know I’m not.”

Saul looked up slowly. His face was older now, not just in years but in distance—from crowds, from accolades, from the crackling energy of a New York book launch.

“I keep wondering,” he whispered, “if I had a voice, or just an echo.”

His friend pulled out a chair and sat across from him.

“You didn’t echo,” he said. “You carved a path through the noise. You made symphonies from inner chaos. And now—maybe now—you’re resting between movements.”

Bellow looked at the pen in his hand.

“It feels like mourning,” he said. “But I can’t name who died.”

“Maybe it’s not someone,” his friend offered. “Maybe it’s an illusion. The one that said your worth came only through words.”

Outside, wind brushed the lake. A single leaf touched the window like a fingertip asking to be let in.

“Do you remember the first sentence you ever wrote?” his friend asked.

Saul’s eyes unfocused.

“I do,” he said slowly. “It was in Yiddish. A story about a lost cat. My brother laughed when I read it aloud. Not because it was funny. Because I sounded... sure.”

“That voice never leaves,” his friend said. “It just hides when you try too hard to find it.”

They sat without speaking. Not from discomfort—but reverence. As if not speaking was the truest form of remembering.

Bellow finally picked up the pen again. Not to write. Just to feel its shape in his fingers.

“You think it’ll come back?” he asked.

“No,” the friend replied. “I think you’ll come back.”

Bellow smiled faintly.

“And if I don’t?”

“Then I’ll sit here,” the friend said, “every morning with you. Until silence becomes story again.”

That night, Saul did not write. But he did read. Slowly. Tenderly. One of his own books, as if encountering the pages for the first time.

And somewhere between a dog-eared paragraph and a margin note from long ago, he laughed.

Only once.

But once was enough.

Chapter 5: The Last Conversation with Death

Setting:

An early winter twilight in Brookline. Snow gently falls outside Saul Bellow’s window. He lies in a modest room, propped up with pillows, a wool blanket over his knees. On the nightstand, a stack of worn paperbacks and an old photograph of his family. A candle flickers beside a bowl of half-eaten soup. His friend sits nearby, holding a small notebook, open but untouched.

Narrative:

Death didn’t arrive with fanfare.

No cloaks. No cold pronouncements.

Just the settling of silence into the folds of the day.

Saul looked out the window and watched the snow erase the outline of the world.

“I always thought it would feel more... grand,” he whispered.

His friend leaned forward, the quiet between them soft as wool.

“And now?” he asked.

Bellow exhaled, not weakly but with precision, like he was whittling down the last shape of a thought.

“It feels like memory. Or maybe fiction. I’m not sure which anymore.”

His friend smiled, not out of comfort but understanding.

“You spent a life blurring the lines between them.”

“I know,” Bellow said, his voice a sandpaper hush. “And now the blur is all I have left.”

They sat together, not speaking, not filling the room with false courage.

The candle trembled once. Then stilled.

“Do you believe,” Saul asked suddenly, “that something waits?”

His friend did not answer right away. He reached down and picked up the old photograph. Saul as a boy, mouth wide with ambition, tie crooked, eyes full of ink.

“I think,” the friend said carefully, “that you wait. Not something. You.”

“And what if I’m not ready?”

The friend looked up.

“You’ve been talking to death for years, Saul. Through every book. Every character. You gave him a voice so readers wouldn’t be afraid to listen.”

Saul chuckled—barely.

“I made him sound like my uncle Hymie once. Remember?”

“You made him sound like everyone we’ve ever loved and lost.”

The snow had thickened outside now. The world hushed itself as if not to interrupt.

“You know what I regret?” Bellow asked.

“Tell me.”

“That I thought knowing more would mean fearing less.”

His friend nodded, gently setting down the photo.

“And did it?”

“No,” Saul said. “But it made me feel less alone in the asking.”

The candle wavered again. A moment passed. Then two.

Bellow turned his head slowly.

“I don’t want to write anymore,” he said.

“You don’t have to.”

“But I want it known. That I could have. That I chose not to. That even silence was still mine.”

“It is,” the friend said. “It’s all yours.”

Outside, the snow covered everything evenly. The mailbox. The stairs. The bent iron railing. No preference. No distinction. Just the quiet mercy of being held.

Bellow’s hand twitched once beneath the blanket.

“There’s a letter I never sent,” he murmured.

“To who?”

He didn’t answer. Just looked past his friend toward the window, as if a boy version of himself were waiting there, waving from the other side.

His friend stood slowly and walked to the desk. The drawer creaked open. Inside, dozens of yellowed pages, neatly tied with a faded blue ribbon.

He brought them to Saul and laid them across his chest like a final offering.

“Read it to me,” Saul said.

“Which one?”

“The one that sounds like goodbye.”

His friend sifted gently, opened one, and began to read:

“I don’t know if I ever became the man I hoped I’d be.

But I stood at the window each day and tried to describe the snow.”

Saul smiled.

“That one,” he whispered. “That’s the one.”

His eyes fluttered shut then, not in fear but in completion. As though the last sentence had finally arrived.

And his friend, holding the pages close, whispered back:

“We’ll keep reading, Saul. We always will.”

Final Thoughts by Saul Bellow

There’s no final sentence to a life, not even for a man who wrote them for a living. What remains are conversations that were never completed, apologies that had no recipients, and laughter that kept us going even when God refused to answer. The writer’s job, I once believed, was to bear witness to the miracle of consciousness. But toward the end, I realized it’s also to forgive the parts of life we couldn’t revise. I’m thankful someone listened.

Short Bios:

Saul Bellow:

Nobel Prize-winning novelist born in 1915, Bellow was known for blending intellectual rigor with emotional depth in works like Herzog, Humboldt’s Gift, and Seize the Day. His writing wrestled with identity, mortality, and the immigrant experience, shaping postwar American literature.

Janis Freedman Bellow:

Saul Bellow’s fifth wife and literary executor, Janis is a scholar and editor who helped preserve and shape the posthumous understanding of Bellow’s legacy through essays, forewords, and curatorial work.

James Atlas:

Biographer of Bellow and author of Bellow: A Biography, Atlas provided an unflinching, deeply researched portrait that sparked both admiration and controversy for its depiction of the novelist’s private life.

Leon Wieseltier:

Literary critic and editor, Wieseltier was a close reader of Bellow’s work, often defending his intellectual and moral legacy in public forums. His essays connect Bellow’s Jewishness to broader existential and philosophical questions.

Zachary Bellow:

Saul Bellow’s son with Janis, Zachary was born when Saul was 84. Though private, Zachary represents a final chapter of Bellow’s fatherhood and late-in-life reconciliation with intimacy and responsibility.

Leave a Reply